Love, Dishonor, Marry, Die, Cherish, Perish by David Rakoff

The special tribute episode, “Our Friend David,” of the radio show This American Life describes writer, performer and show favorite David Rakoff as a much-loved man who had “dozens of friends.” This stands in contrast to his literary persona as an acerbic, dry, self-deprecating culture creature with a purring voice. That carefully crafted persona apparently often felt like a burden. In life, Rakoff was a Canadian ex-pat who struggled with cancer, but in his work he could be both brutally honest and wickedly incisive in a quintessentially New York way, full of hair-trigger jabs one moment and all-too recognizable pain and self-loathing the next.

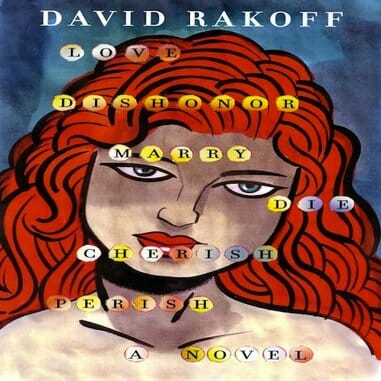

Rakoff died last summer a few years shy of 50, relatively soon after finishing his final book, either a long poem or a short novel (depending on how you look at it) told in rhyming couplets with accompanying illustrations. He gave it the curious title of Love, Dishonor, Marry, Die, Cherish, Perish. He rendered these seemingly contradictory pairs on a chunky, baby book-style cover with the image of a bold, beautiful redheaded woman overlaid on a psychedelic matrix of swirling colors…with holes punched out for each letter.

The face comes as the first of many we see in this sometimes dawdling but consistently admirable work. If Love, Dishonor is not sui generis, it’s definitely sui Rakoff, which could even be a higher distinction.

The story begins in the early half of the 20th century with the birth of a girl named Margaret (perhaps later the mysterious redhead on the cover?), to an unnamed mother in Chicago.

From there, we hop around in separate sections to the perspectives of an assortment of troubled souls lost in the following generations. An artist named Clifford grows up to join the underground comix scene of San Francisco and create gay porno Batman parodies. We meet Susan, an art gallery worker, Nathan, her bitter ex-boyfriend, and Clifford’s cousin, Helen, who despite herself might be the character who comes closest to achieving some sort of lasting happiness.

In (mostly) tightly woven lines, Rakoff drums us through numerous decades, inner monologues and outer tribulations, taking the sort of meter that usually calls Dr. Seuss and Christmas to mind and applying it to subjects like adultery, AIDS, sexual abuse, abortion, alcoholism and dementia. The contrast may have been a big part of the appeal of this project, and fits in with a larger theme—a tug between opposite poles that threatens stability.

As the story continues, familiar faces grow old and tired. A disgraced teenage Margaret hitches a ride out of town (and effectively out of the story) on a train. Then the focus shifts to the talented Clifford, who goes on to have a key encounter with Helen, the latter posing for a flirtatious photo with oranges held in front of her bare breasts. This image returns throughout the narrative, perhaps as a symbol of the good times we always have to struggle to hold onto.

The cartoonish drawings (by the Canadian artist Seth), tactile construction and rhyme scheme make the entire production further seem like a rediscovered 1950s nursery collection corrupted by the years. Foremost, we should think of it as a work of great construction, or, as Rakoff puts it, referring to his character Clifford’s art practice:

“torments endured with a saint’s skyward smile, nuance, technique, composition and style.”

Rakoff, who experimented with such sophisticated verbal patterns in memorable radio pieces like his bittersweet Gregor Samsa/Dr. Seuss correspondence, has an obvious familiarity with such neo-formalist shenanigans. Here, he similarly deconstructs the associations we have with anapestic tetrameter (dubba-DUH dubba-DUH dubba-DUH dubba) as “children’s verse,” just as the monochrome character portraits separating the different ‘chapters’ draw us back to visions of more innocent tomes…but instead show us visages that appear angry, lustful, pompous, confused, defeated.

Many an English student may remember that rhymes can suggest duality, a pattern we can understand, the eternal coin flip of high and low. Love, Dishonor mostly resists the use of enjambment to blend lines together, instead driving us again and again back to the lockstep feeling of setup/punchline. The closer you enter into the entirety of the book’s vision, the more it works: As Rakoff’s scorpion says, “my form is my function.” (One of the moments where Rakoff cleverly changes his style comes when a character actually tries to speak in verse and fails.)

The motif crucial to Rakoff’s moral comes out in the central passage, a disastrous toast given by a still-seething Nathan at Susan’s wedding. It re-tells the fable of the scorpion and the tortoise (or is it a turtle?). In its tale of a good thing undone by a needless sting, the fable echoes something nearly all of the characters encounter in one way or another, whether the appearance of HIV in the artistic and sexual Utopia of the Castro…or the arrival of Alzheimer’s, decrepitude and regret in old age.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-