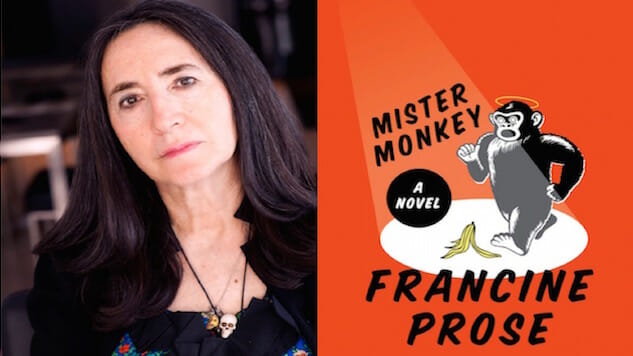

Francine Prose Weaves Cringe-Worthy Moments Around a Musical in Mister Monkey

Photos courtesy Christine Jean Chambers

Like Lovers at the Chameleon Club, Paris 1932, the spellbinding roman à clef that preceded it, Francine Prose’s novel Mister Monkey is another multiple-perspective marvel, awash in wonderfully realized characters whose lives collide and unfold in parallel. But the similarities end there.

Chameleon Club combined an abundance of absorbing historical detail from pre- and post-occupation Paris with an array of narrators taking unreliability to historic heights. Mister Monkey, by contrast, unfolds entirely in present-day New York City. It spools out from an off-off-Broadway children’s musical disrupted by a child in the audience loudly asking his grandfather, “Are you interested in this?” Each chapter picks up the story from a new angle, re-situating itself in the thoughts of another character positioned outside the spotlight in earlier scenes. Each character gets one star turn and then cedes centerstage to another.

In no particular order, we meet: Margot, a middle-aged actress plagued by absurd costume choices and utter disbelief that she needs gigs like the Mister Monkey musical to make ends meet; Miss Sonya, a young Brooklyn kindergarten teacher who blunders into an ill-advised classroom discussion on evolution and shortly thereafter finds herself in a blind date from Hell; Ray, the author of the classic children’s book mercilessly hijacked by the musical in question, who observes the teacher’s date from Hell first-hand; and several other colorful individuals. Few novels in recent memory careen so delightfully from mid-life melancholy to make-you-squirm comedy.

In anticipation of Mister Monkey’s release today, Paste connected with Francine Prose to discuss perspective-shifting fiction, bad dates and dinner parties, promising artistic careers gone awry and writing without an outline.

![]()

Paste: Lovers at the Chameleon Club intertwined several distinct voices and richly imagined stories, but given that some of these characters and stories were based on real people and events, it also had historical marks to hit. Writing the layered narrative in Mister Monkey must have been a very different—not necessarily easier—kind of writing experience.

Francine Prose: It was much more fun. With Chameleon Club, I knew where it was going. In fact, one of the reasons I started Lovers at the Chameleon Club where I did [in time, several years before the war and the occupation], was because I knew how dark it was going to get by the end. I wanted to make it clear how bright it was at the beginning.

With this new novel, I keep seeing it described as “darkly comedic.” I never thought of it as that dark. I think the characters at the beginning of the book are going through hard times, in the way that many people do, and then they all have redemptive moments which were big surprises to me by the time I got to the end.

Obviously, what the two books have in common is that they’re told in different voices and the voices all belong to people who are, as we find out, very closely connected to one another, but they move in different directions. Chameleon Club started bright and got dark; Mister Monkey starts a little darker and gets bright.

Paste: At the beginning of Mister Monkey, if feels like it’s going to be Margot’s book, because it starts in her voice and her frustrations are so familiar. It’s hard not to identify with her.

Prose: I’m sure for everyone who has ever been an artist, or tried to be an artist, or has thought about being an artist, Margot is the nightmare that looms in your brain a lot of the time. It could happen to anybody: You wind up playing the lead in Mister Monkey even though you thought you were going to be playing in Chekhov in Lincoln Center.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-