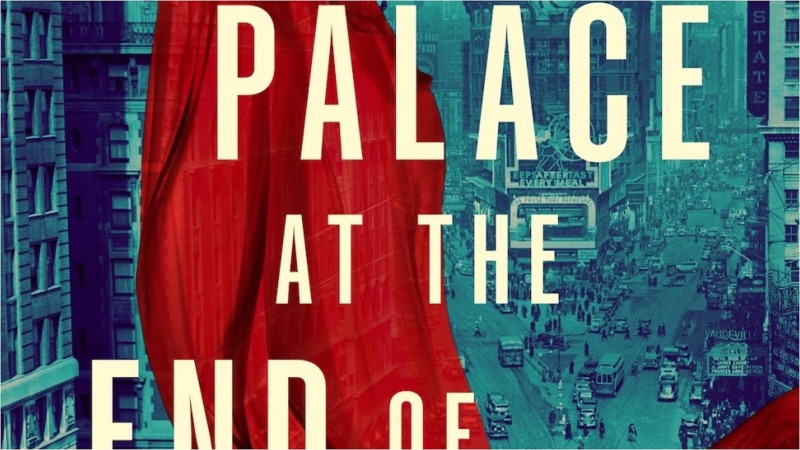

Read an Excerpt From Simon Tolkien’s Historical Fiction Epic The Palace at the End of the Sea

While J.R.R. Tolkien is known for writing high fantasy, his grandson Simon Tolkien has taken a different literary tack. Though his writing career began with a trilogy of mystery novels, he has since taken a turn into historical fiction. His 2016 novel No Man’s Land was at least partially inspired by his grandfather’s experiences during World War I, and his next duology is set to dive even deeper into a specific historical setting. The Palace at the End of the Sea follows the story of a young American who crosses continents looking to find himself—and is swept up into the Spanish Civil War.

A sweeping, panoramic story of family, disillusionment, love, circumstance, and hope, it’s an epic saga that wrestles with political ideologies, political beliefs, and the effects they have on the world around them—from vast countries right down to the individuals who live in them.

Here’s how the publisher describes the story.

New York City, 1929. Young Theo Sterling’s world begins to unravel as the Great Depression exerts its icy grip. He finds it hard to relate to his parents: His father, a Jewish self-made businessman, refuses to give up on the American dream, and his mother, a refugee from religious persecution in Mexico, holds fast to her Catholic faith. When disaster strikes the family, Theo must learn who he is. A charismatic school friend and a firebrand girl inspire him to believe he can fight Fascism and change the world, but each rebellion comes at a higher price, forcing Theo to question these ideologies too.

“Through intense research over many years,” Tolkien said, “I have tried to bring the vanished world of America, England and Spain in the 1930s to life – a time that shares many similarities with the troubled world we live in today. I believe in the value of historical fiction. The past is another country just as rich as ours, and I want to bring it to life.”

The Palace at the End of the World will be released on June 1, and we’ll be closely followed by its sequel, The Room of Lost Steps, which is set to arrive on September 16. In the meantime, we’re thrilled to give you a chance to read the first chapter for yourselves below.

![]()

1

KIDNAP

He was eleven when he was taken. On a day of early summer from almost outside his apartment house out into the bustle of the Village, and then east across Third Avenue under the webbed iron feet of the roaring El into regions of the great city that he had never seen before, smelling of garbage and horse dung and thick, acrid smoke.

And all the time, the old man held Theo’s hand in an iron grip and kept up a quick pace, pulling him along the sidewalk, so he had almost to run if he wasn’t to fall over. He had seen the old man several times in recent weeks, waiting under the spreading chestnut tree at the corner of his street in the early evening. He’d stared at Theo and his mother as they went past with his eyes glowing like coals under the rim of his battered old derby hat, which he wore as if it were an upturned soup bowl, pulled down over his ears like Charlie Chaplin.

He had the hat on now and the same long black alpaca coat, shiny at the elbows, which he was wearing over a clean but frayed white shirt buttoned to the collar with no tie, and Theo could see that in the side of his scuffed shoe there was a small hole that opened and closed as he walked, as if it were another beady eye.

He told Theo that he was his grandfather, speaking slowly in a thick guttural accent, and Theo thought he probably was. He didn’t look like someone who told lies, and besides, there was something about the old man that reminded Theo of his father. Four days before, they’d been walking home and his father had stopped hard in his tracks, telling him sharply to get on home to his mother. But Theo had turned back at the stoop and had seen his father arguing, waving his hands in the air but seeming to have no effect on the old man, who stood there as immobile as the tree behind him. And maybe it was then that Theo had noticed the resemblance.

Afterward, his parents had talked in hushed voices and his mother had cried as she often did, and his father had gotten hot under the collar and said that there were laws to stop people being harassed in the street, and that he had a good mind to complain to the authorities if it happened again. Authorities was one of Theo’s father’s favorite words—he was a great believer in law and order. But it seemed like there was no need to get them involved this time. There were no further sightings of the old man, and today Theo’s mother had woken up with another of her terrible headaches—the curse she called la jaqueca—and had sent him to the pharmacy on MacDougal with a quarter to get some more of her yellow pills. And on the way, without any warning, it had happened.

The old man had not been in his usual place under the tree; instead, it was as if he had appeared out of nowhere like a circus magician, and Theo was so surprised that he didn’t try to resist, at least at first, allowing himself to be led away with his small hand still clutching his mother’s coin, all enclosed inside the old man’s huge calloused palm.

His grandfather could have been sixty or seventy or eighty, a hundred even. Theo couldn’t tell. He knew only that he was taller than anybody he had ever seen and that his flowing white beard made him look like one of the Old Testament prophets in the illustrated Bible that his mother had given him the year before to celebrate his First Communion. Moses, perhaps, leading the people of Israel across the desert, or Jonah, who got swallowed by the whale; although most of all he reminded Theo of crazy Abraham, who was ready and willing to sacrifice his son until God stopped him on the top of the mountain, just in the nick of time. That picture was one of the scariest in the whole book, and Theo, closing his eyes, could see the long, glittering knife that Abraham had ready for the awful deed, raised high above his shoulder while he held Isaac pinned in place on the stony altar with his other hand.

Now, suddenly, Theo was terrified, and at the next corner he used all his strength to try to break free.

“Help!” he shouted, but he couldn’t shake the old man’s iron grip and his cry froze in his throat, coming out as a sort of croak to which no one passing by paid any attention.

“Where are you taking me?” he asked, looking up into his grandfather’s strange but familiar face. The eyes were different from his father’s: narrow yet penetrating, set back amid the hollows of a wrinkled face, but the thin, determined mouth and the jut of the chin were the same.

“I am taking you to meet your bubbe . . . your grandmother,” the old man added, seeing Theo’s look of incomprehension. “It is nothing to be scared about—it is . . .” He stopped, and the wrinkles in his forehead bulged as he searched for the English word. “An adventure!” he finished and smiled, a quick movement of his lips that was fleeting but nevertheless enough to make him seem more human, so that Theo didn’t resist when the old man resumed their walk. Slower now, as if to reassure the boy.

“Why do you talk funny—like you don’t know the words?” Theo asked.

“Not like your father, you mean?” the old man replied sharply.

“I guess,” said Theo defensively. He was frightened again, thinking that he might have upset his grandfather with the impertinence of his question.

“Because I come from another country. Far away across the great sea. Just like your father, but he has forgotten that. He has turned his back on who he is, become something he is not,” the old man added harshly and picked up his pace.

But he couldn’t go much quicker because the city had changed and the sidewalks were packed with the laden pushcarts of peddlers that overflowed out into the street, where horses and delivery trucks and dirty automobiles mingled in a maelstrom of pent-up, impatient movement. The drivers blew their horns and crept forward at a snail’s pace, cursing through their windows at impervious pedestrians who weaved their way between the wheels, wrapped in trails of gassy exhaust smoke that made Theo’s eyes water.

On the opposite corner, a traffic policeman stood on a box and waved his white-gloved hands with self-important, theatrical gestures, but Theo knew there was no chance the cop would hear him above the din if he shouted, and he realized with surprise in the next moment that he didn’t want to shout. He wanted to meet this bubbe, who was waiting for him somewhere among the gray-brick tenement buildings that towered up on both sides of the road. Narrow and tall with the sloping iron fire escapes clinging to their sides like a multiplying species of parasitic insect.

They turned a sharp, unexpected corner onto a smaller, quieter street, leaving the traffic behind. It was hot under the climbing sun and the asphalt of the sidewalk felt like it was bubbling under their feet, and Theo’s head began to swim as he looked longingly across to where a group of shaven-headed children were holding hands and dancing with quick steps around a squirting fire hydrant, singing songs in a language he couldn’t understand.

Abruptly, Theo’s grandfather stopped. In front of them, a humpbacked old woman with a wart-covered face, partially concealed by a red kerchief, had parked a baby carriage across the sidewalk, and now she challenged them in a high-pitched screech to “buy, buy, buy,” eagerly pulling back a frayed checkered cloth to reveal not a baby but a pot of steaming black-eyed beans.

“Not now, Rachel,” said the old man impatiently and, stepping around the carriage, he pushed open the door of the tenement building behind her and, still holding Theo’s hand, began climbing the steep winding stairs, which spiraled up and around above their heads into a shadowy gloom. It was cool inside, and in the semidarkness Theo felt as if they were going down and not up—into an underworld lit by small gaslights on the dreary landings. They flickered in the draft from a door that opened and closed somewhere above their heads, releasing a burst of voices speaking in that same strange language that he had heard outside on the street.

Up and up and around and around with the smell of urine and worse clinging to the crumbling lime-green plaster walls, until they were almost at the top. And then on the last-but-one landing, just as Theo thought that he was either going to be sick or collapse or both, his grandfather halted in front of a low door with a brass number 9 nailed slightly askew to the outside. He let go of Theo’s hand and extracted a key from a pocket somewhere deep inside his coat and unlocked the door, ushering Theo inside.

Inside into another world, or that was how Theo thought about it afterward. He was suddenly hot again. It wasn’t from the sun, which was no more than a dim glow through tiny, dirty windows shaped like portholes at the back of the long room that they had just entered, but rather from a large kitchen stove, halfway down the right wall, that was giving off heat like a furnace. Iron pots were boiling on the top, similar to Rachel’s down below, and a woman with a blue scarf tied around her hair was using what was left of the surface to heat a pressing iron that hissed and spat like a live creature.

There were people everywhere. Theo thought he had never seen so many in one room, sitting in corners or in a tight group at one end of the long kitchen table. They were working at sewing machines or cutting bundles of cloth, which seemed to be piled up on all sides in a dazzling array of colors and shapes, including a few feet away from the door, where they were stacked high enough to make an improvised bed upon which a small boy half Theo’s age lay fast asleep.

So many sensations he felt all at the same time: the smell of unfamiliar food, the stifling heat of the stove, hands touching him from all sides, and a cacophony of voices talking over each other in that same language he couldn’t understand. He was excited and curious but not frightened, which surprised him afterward because he thought he should have been. Perhaps it was because he felt he belonged, but how could he, when everything was so alien? It made no sense to him then or later, when he often thought about this moment, turning it over in his mind.

A voice cut in, louder than the rest, telling the others in heavily accented English to “leave the boy alone, let him breathe, let me see my grandson.”

They pulled back and there she was: his bubbe. Short and round— the opposite of his grandfather—with a yellowish face pockmarked and double-chinned under a halo of iron-gray curly hair, but transformed by enormous, wide-open, emerald-green eyes that seemed to drink him in and look straight down into his heart.

She put her hands on his head, pressing them slowly down over his ears and then, as if satisfied by what she found, drew him to a chair at the table, where he saw that there were different dishes already laid out on gleaming white porcelain plates. They were small and delicately made and all the colors of the rainbow. Standing over him like a sentinel, she watched him eat each one, telling him the names in halting English: pastries called blintzes with goat cheese inside that came from the blind dairyman on Hester Street, who kept his own animals out in Bronx Park; kraut and potato knishes; pickled tomatoes grown by his grandfather up on the roof—the best in all the Lower East Side, better even than what the Italians produced and “nobody has green fingers like them”; and last but not least a sponge cake made with quince jam—quinces that were good, she said, but not as good as they used to be in the old country in the springtime, when she and her sisters were young and climbed the trees like squirrels and came home exhausted, with the precious fruit tied up inside their coats.

Theo ate with concentration, intoxicated by the variety of exquisite tastes he had never before experienced, and when he had finished, his grandmother called to the woman in the scarf to bring more: stew and beans from the pots on the stove. “It is cholent,” she said, and made him repeat the word, pronouncing each syllable separately. “Jews have eaten it always. We cook it on Fridays so we can eat it hot on Shabbat.”

“Shabbat?” he asked. “What’s that?” He felt drowsy and more than a little nauseated. He had eaten too much already, and he looked longingly over at the sleeping boy in the corner, hoping he might join him on his bed of cloth. But he couldn’t because he could see there were tears in his grandmother’s beautiful eyes and he knew he’d said something wrong, but he did not know what it was.

It was his grandfather who came to the rescue. “It doesn’t matter, Leah,” he said gently, putting his hand on his wife’s shoulder. “The boy will know these things in time, but it is us that he needs to understand now. Who we are, who he is. It is what we spoke of before.”

The old woman sighed and nodded, and going over to Theo, she took his head again between her hands and kissed him once on the forehead and then retreated back toward the stove. And Theo’s grandfather took off his coat and sat down on the other side of the table, fixing his pale-blue eyes on the boy, just as he had when Theo had first seen him, standing under the tree at the end of the street in the twilight.

“There’s not much time,” he said quietly. “Your father will be here soon.”

“Why? How do you know?” Theo was afraid again now, but not of his grandfather. He feared what his father would do when he came, and whether he would bring the authorities with him to punish the old man and his wife. Theo didn’t want that.

“He will know it was me who took you,” said his grandfather simply. “And when he comes, you will leave and you will not be allowed to come back.

Perhaps you will never see us again. But you will remember. What is inside your head—that no one can change.”

Theo nodded. He knew instinctively that his grandfather was right. He would never forget. Each moment, his eye and his brain were recording, selecting items for preservation: the stenciled gold of the inscriptions on the black Singer sewing machines, the cotton spools, the colors of the cloth, the smell and taste of the food so lovingly prepared, the faces and the bodies of his grandparents so much a part of him and yet so fleetingly known.

“What is your name?” asked his grandfather.

“Theo,” he said, surprised. It shocked him that this man should be his grandfather and yet not know his name.

“Thee-o,” repeated the old man slowly. “What kind of a name is that?”

“It’s short for Theodore. Like the president. That’s who Dad named me after. The one who killed the elephant.”

“Which was a terrible thing,” said his grandmother, vigorously shaking her head. “Devil’s work.”

“Quiet, woman!” said Theo’s grandfather, raising his hand for silence but keeping his eyes on Theo. “We have no time. I told you that.”

“And what is your last name?” he asked, returning to his questioning.

“Sterling. Like sterling silver. Dad says it’s a solid name that people can rely on in business,” Theo volunteered. It was a favorite saying of his father’s, so often repeated that it had become like a family mantra.

“Solid, perhaps, but not true,” said the old man. “Your name is not Sterling; it is Stern. Your father changed it because he denies who he is and who you are. He can do this for himself, but not for you. You have a right to know.”

“What is Stern?” Theo felt confused again now, and anxious, and his voice was faint.

“It means star in our language, in Yiddish. It is a beautiful name—for the star that guides us. I am Yossif—Joseph Stern.”

“Like Joseph, Jesus’s father,” said Theo, thinking of the bearded, kindfaced figure in the blue cloak and sandals that his mother put out beside the crib before Christmas with Mary and the baby. Up on the mantel in a miniature Bethlehem, before the shepherds and the kings who came after, each on their appointed day.

“No, like Joseph, Jacob’s son, who was sold into slavery in Egypt and yet found his way to prosper and help his brothers, without ever forgetting who he was and where he came from. Perhaps one day you can be another Joseph,” said the old man and smiled suddenly in that same unexpected way he had on the street when he had promised Theo an adventure. “Look,” he said, reaching up and taking down an old battered photograph album from a shelf behind his head. “These are your ancestors. In Poland, where the winters are colder even than here and the goyim are cruel.”

The old man slowly turned the pages, and Theo saw a succession of sepia faces. Men and women and children posed in their best clothes, looking trustfully forward into the camera lens. In one picture, there was a dog with a ribbon seated on a chair and a boy standing beside it dressed in a sailor suit, and there were several of a long wooden house with two smoking chimneys and people standing in front of it, lined up against a paling fence. They meant nothing to Theo and perhaps his grandfather sensed this, because his tone became more severe.

“They were killed. Not all of them, but most. This was my house—where I was born, and where my mother and father died,” he said, pointing at the pictures.

“How did they die?” asked Theo in a whisper.

“Fire,” said the old man, pronouncing the word as if it was a curse. “My parents tried to come out but the goyim would not let them. They burnt them alive and danced around the flames, singing songs. Everywhere they did this. Sometimes before, they would say, ‘You can become Christian, be baptized, and live,’ but the Jews refused. They had no choice: they had to be true to who they were. Because without that you are nothing, worse than nothing. Do you understand?”

Theo nodded even though he didn’t understand and didn’t want to. He was terrified now and wanted the adventure to end; he wanted his father to come and rescue him. And as if in response, a violent knocking began at the door and he could hear his father shouting, demanding to be let in.

“Quicker even than I thought,” said the old man with a sigh, closing the book and replacing it on the shelf behind him.

The spell was broken. “Let him in, Leah,” he told his wife. “What must be must be.”

She opened the door and Theo’s father crashed into the apartment, losing his balance and falling on the sleeping child in the corner, who promptly woke up and began to cry.

But immediately Theo’s father was back on his feet and pulling Theo up from his seat with one hand, while his other fist was clenched, drawn back as if to hit the old man, who had remained in his chair throughout the commotion, just as immobile as he had been under the chestnut tree.

“How dare you! You had no right!” Theo’s father spoke breathlessly. Theo had never seen him so angry.

Theo’s grandfather briefly replied, but Theo couldn’t understand what he was saying because he was speaking in that foreign language that he had heard earlier: a harsh jangle of sounds that made Theo even more scared. He clung to his father, burying his face in his shoulder.

“Speak English!” Theo’s father shouted at the old man. “We aren’t in Poland anymore, however much you’d like to think we are. And no, I won’t take the boy and go. I’m not here to do your bidding.”

But Theo’s grandfather said nothing. Just stared blankly at his son, as if challenging him to do his worst. Behind him, Theo’s grandmother had begun to cry, but her husband raised his hand again as if in warning, and she was quiet. Now, for the first time, Theo sensed the old man’s true power: nobody in the whole room stirred or made a sound.

Theo could feel his father trembling, and it made him remember the Christmas before last when it had snowed so hard that the automobiles almost disappeared and he’d held on to his father so tightly as they’d pushed through the blizzard, coming back home from the store. It had been hot in the apartment, but he had had the same sense of an overpowering force field pressing against them.

Then, suddenly and unexpectedly, his father laughed and unclenched his fist, dropping his arm to his side, while keeping his other around Theo’s shoulder.

“You old fool!” he said, spitting out the words to underline his contempt. “Thought you could take my son and make a Jew of him in a couple of hours! A few plates of herring and pickled onion and some cholent stew and he’s yours for life. Is that it?”

Theo’s grandfather shook his head but said nothing.

“No, even you aren’t that stupid, are you? Jewish blood comes from the mother, not the father. Theo’s a Catholic like his mother and there’s nothing you can do to change that, however hard you try.”

The old man nodded, an almost imperceptible movement, keeping his eyes fixed on his son.

“So why did you have to take him and put him through all this? What was the point?” Theo’s father’s voice rose as his anger threatened to get the better of him again.

“Because he’s all we have, Leah and I,” said Theo’s grandfather quietly, framing each word with care. “No one here is our blood. And when we are gone, he will be the only one left to know. So I must tell him what you won’t. Who we are, where we came from, who we left behind . . .”

“We! What about me? I know all that. I’m your son, aren’t I?”

Theo thought he could hear an appeal in his father’s voice, breaking out from behind his fury, but it had no effect on the old man.

“You’re an apostate. A Jew who preys on his own people like a wolf in the night.”

Theo could hear the venom in his grandfather’s voice, coming from a place where there was no possibility of forgiveness.

“I’m not ashamed of what I do,” said Theo’s father, refusing to be cowed. “I work hard and try to get ahead because I believe in this country—it’s my promised land. But you—you are here but not here. Living like animals, packed ten to a room with rats in the ceiling and garbage on the streets. Overflowing toilets on the landings. I know: I lived here long enough. And nothing has changed for you since you hauled your calico seabags up from Ellis Island. And nothing will because you won’t let it. That’s why I left.”

Silence. The old man made no response, just stared through his son as if he weren’t there. Theo felt his father’s hand quivering on his shoulder, and then he lifted it and put it under Theo’s chin, tipping his head up so that he could look into his eyes.

“Do you know why they treat me like this, son?” he asked. “Like I don’t exist? Did they tell you that?” Theo shook his head.

“Because I married your mother. That’s why. I married a goy.” “A goy?”

“A Christian. Someone who is not a Jew. I married for love, not because one of their matchmakers had found me a woman. And for that they sat shiva for me. They covered their mirrors and swayed from side to side and muttered their crazy prayers, and at the end of seven days I was gone. Dead even to the woman who bore me,” he said, looking over at his mother, who hid her head in her hands and started crying again.

“And now, now I am a ghost,” he went on, raising his voice. “I am not here. I don’t exist. None of this is happening.”

Still with his arm around his son, Theo’s father turned and pulled down a small wooden object shaped like a finger that was hanging by the doorpost. Theo hadn’t noticed it until now. In his father’s hand, he could see there was writing in strange letters on its side.

Theo’s father held it for a moment and then very deliberately threw it on the ground, where it broke open, revealing some form of parchment.

With a cry, Theo’s grandfather jumped up from his chair and, rounding the table, went down on the floor to gather the broken pieces together in his shaking hands. His son looked down on him with an expression Theo had never seen on his father’s face before: despair and exultation, sorrow and contempt, all mixed up together in a rictus of extreme emotion.

“I’m no Jew and nor is my son,” he said, spitting out the words. “We’re Americans.” And pushing Theo in front of him, he pulled open the door of the apartment and left without looking back.

They walked quickly, turning north when they reached Broadway and not pausing until Theo’s father branched off to the left and went into Washington Square, where they sat down on a bench. Now they were back in familiar territory. His father often brought Theo here on Sunday afternoons to watch the chess hustlers play under the canopy of the oak trees, while the fountain sprayed its jets high in the center of the park, and sometimes a saxophone or trumpet player would send melancholy tunes winging on the air out through the arch toward Fifth Avenue, while his upturned hat lay on the ground in hope of recompense.

Theo’s father would stand beside the tables, avidly following the players’ moves, never tiring of seeing the hustlers getting the better of their social superiors; and then afterward, as they walked home, he would talk admiringly of how anyone could beat anyone in America because it was the land of the free (another of his favorite phrases) and the opposite of the country he had come from, where the common people were born into servitude and no one could get ahead unless they were born with a silver spoon in their mouth or saved or stole enough money to buy a steerage ticket on a boat to New York.

But now he was silent, gazing off into space and sometimes shaking his head, as if he were continuing the conversation he had just held with his unforgiving father.

“What was it you threw on the floor?” asked Theo. The events of the day had left him feeling traumatized, and he needed the reassurance of his father’s voice.

“It was a mezuzah. The Torah—the Bible, I mean—instructs Jews to write the words of God on the gates and doorposts of their houses. The mezuzah is the container; the words are written inside.”

“On the paper?”

Theo’s father nodded. “I broke it because that’s the only way I could get my father to react. I needed him to show some emotion, something to make me feel I exist. There’s nothing worse than when your father looks through you like that. I won’t ever do that to you. You understand that, don’t you, son?” he asked, becoming emotional suddenly.

Theo nodded, frightened by his father’s intensity.

“What did he say to you? Before I came?” Theo’s father had his eyes fixed on his son’s.

“That I’m not called Sterling. I’m Stern. Like a star. He showed me pictures,” said Theo, becoming upset.

“What pictures?” his father pressed.

“Pictures of dead people,” said Theo, his voice now no more than a whisper.

His father nodded, thinking. And then suddenly smiled, as if he’d made a decision. “You must forget,” he said, snapping his fingers. “Forget all of it, like it was a bad dream. He will not bother you again, I promise. We have the future to think of now, not the past, yes?” Theo nodded.

“Good. So you promise?”

Again, Theo nodded, and his father, obviously pleased, bent down and kissed him on his forehead. “You will be following in my footsteps at the factory before too long—Sterling and Son of New York City: Now that’s got a good ring to it, hasn’t it?”

Afterward, in the weeks that followed, Theo wished that he had asked his father more questions about his grandparents, but by then it was too late. He had agreed to a compact of silence, and he and his father never spoke of the kidnapping again.

Excerpt from THE PALACE AT THE END OF THE SEA by Simon Tolkien

Text copyright © 2025 by Simon Tolkien, Published by Lake Union Publishing

A Palace at the End of the Sea will be released on June 1, but you can pre-order it right now.

Lacy Baugher Milas is the Books Editor at Paste Magazine, but loves nerding out about all sorts of pop culture. You can find her on Twitter and Bluesky at @LacyMB