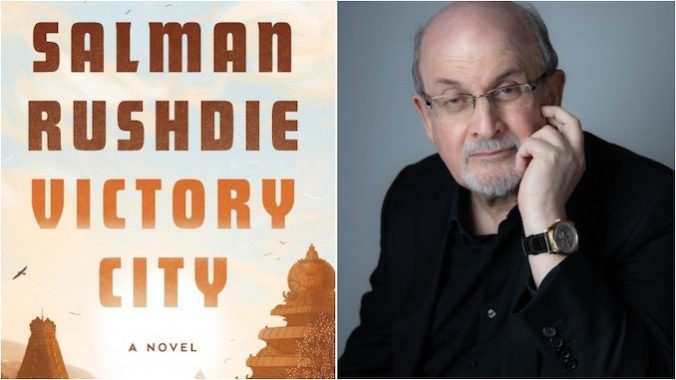

The Curmudgeon: Salman Rushdie Creates An Unruly Kingdom

Photo by Rachel Eliza Griffiths, courtesy of Random House Books

Pampa Kampana, the main character in Salman Rushdie’s new book, Victory City, creates an entire kingdom in the southern half of what is now India. When she is orphaned at age nine, after her mother has thrown herself onto a funeral pyre in the book’s dramatic opening, she is possessed by the goddess Parvati. Nine years later, she discovers that she has the power to use seeds of grain to grow an entire city and fill it with soldiers, bakers, poets, and more.

Of course, Rushdie is doing the same thing as his heroine: he’s creating a society with tens of thousands of citizens from something as negligible as a bag of seeds: his imagination. And like his protagonist, he does a very good job of it—conjuring up a whole world that’s thoroughly believable, from its Hindu architecture and stories to its quarreling factions and bloodthirsty armies, from its randy libertines to its religious ascetics, from its towering walls to its nearby dense jungles.

Pampa Kampana names her grown-overnight metropolis Vijayanagar or Victory City. Its citizens, though, soon slur the word into Bisnaga. It won’t be the last time the creator’s intentions are twisted into something else. There really was a Hindustan empire named Vijayanagar that ruled much of the region from roughly 1318 to 1565, the 247 years of the entirely fictional Pampa Kampana’s lifespan. That life is elongated by Parvati’s magic, for Victory City the book is a fable, not a history.

Both Rushdie and Pampa Kampana try to nudge their invented societies in an enlightened direction, encouraging their creations to embrace religious tolerance, gender equality, and artistic freedom. Both creators are disappointed. It turns out you can’t make your invented world realistic and utopian at the same time. As much as these two writers long for a better society, their first loyalty is to reality and to the flexibility of language, even if that makes them enemies of the world’s utopians.

Rushdie has famously been the enemy of Islamic utopians. In early 1989, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for Rushdie’s death, after the author had depicted Mohammed as a complex human being in the 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses. Between finishing Victory City and seeing it published, Rushdie was nearly killed when a fatwa-inspired young man stabbed him repeatedly in the face, neck, and abdomen last August on a stage in Chautauqua, New York.

More recently, Rushdie earned the ire of left-wing utopians when he condemned the campaign of neutralizing the language in Roald Dahl’s classic children’s books to make them more politically correct. Whether writing about Mohammed, Dahl or Pampa Kampana, Rushdie has insisted on the right to portray them as flawed, complicated, admirable, flesh-and-blood beings rather than plaster saints or demons.

Pampa Kampana runs into similar problems. After sowing her magic seeds to grow the city of Bisnaga, she whispers personalities and histories—with her own progressive sympathies—into the blank-slate humans who have sprung up from the same seeds. It works. But a generation later, the citizens have developed their own needs and want, and they disregard her further instructions.

Early in the book, Rushdie describes how Pampa Kampana supplied inner lives to the thousands of people she had raised from seeds in the desert sand. While she’s in the middle of that whispering campaign, the empire’s new crown prince brings a Portuguese trader to observe. Even as Pampa Kampana is making her world more defined and believable, Rushdie is doing the same with his.

“It was a small room, unlike any other room in the palace,” Rushdie writes, “not in the least ornate, with plain whitewashed walls, and unfurnished except for a bare wooden plinth. A small high window allowed a single ray of sunlight to descend at a steep angle toward the young woman below, like a shaft of angelic grace. In this austere setting, struck by that thunderbolt of startling light, sitting cross-legged, with her eyes closed, he arms outstretched and resting on her knees, her hands with the thumbs and index fingers joined at their tips, her lips slightly parted, there she was: Pampa Kampana, lost in the ecstasy of the act of creation.

“She was silent, but it seemed to Domingo Nunes, as he was ushered into her presence by Bukka Sangama, that a throng of whispered words were flowing from her, from her parted lips, down her chin and neck, along her arms and out across the floor, escaping from her as a river escapes from its source, and heading out into the world.”

The act of creation has its moments of ecstasy, Rushdie accurately reports, but it also has its moments of frustration. Sometimes you want the words to come, and they stubbornly refuse. Sometimes you want your characters to act a certain way, and they refuse. If you’ve done a good job of creating them—if you’ve raised them like independent children—they will have their own desires, their own agendas, and will resist yours.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-