Ten Years Later: Moore & Gebbie Exposed the Sexuality of Literary Heroines in Lost Girls

This article contains NSFW illustrations of full-frontal nudity and is intended for mature readers.

Depending on where in the world you’re sitting as you read this, it may not be legally advisable to purchase Lost Girls, Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s massive erotic upending of the leading ladies from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and Peter Pan. First published in its entirety by Top Shelf ten years ago this summer and set in 1913 during the tumultuous days leading up to the first World War (Archduke Franz Ferdinand meets his end while the protagonists fondle one another in the audience of a play), Lost Girls is undeniably pornography: in form, in potential function and in Moore’s own words.

It is very nearly every kind of pornography, too. A handsome man first seduces a young American girl (Dorothy, formerly of Kansas) who indulges his shoe fetish before anally penetrating the older, apparently heteroflexible husband of a repressed Wendy, terribly far from her teenage Neverland. A silver-haired Alice rediscovers Wonderland as she lays a sprightly young maid with the assistance of a porcelain dildo. In one of many asides from the primary plot, a family of four engages in every conceivable combination of incest, son and daughter clearly below the teenage threshold. Most of the book, in fact, challenges obscenity laws and definitions of child pornography. Preteen brothers explore their sexuality, a young street urchin turns tricks to survive and Alice falls prey to the manipulations of a predatory white rabbit. To remove any ambiguity in the minds of those who have yet to read the book, Gebbie draws every adolescent sex act in full detail, often in lush crayon. Lost Girls does not allude and suggest when it comes to its XXX-rated content.

The length of the story—over 300 pages—allows Moore and Gebbie to touch on budding sexuality in nearly every permutation. Alice, whose founding novel was frequently interpreted to represent emerging womanhood long before Moore and Gebbie serialized Lost Girls in the pages of Steve Bissette’s appropriately named Taboo anthology, suffers the most in transition from Lewis Carroll’s frabjous source material. Her awakening is a forced one, coerced into sex with an older man when she is only 14. Her Wonderland, the topsy-turvy, otherworldly dimension that has made untold millions for Disney throughout the decades, is her way of escaping reality during these repeated violations.

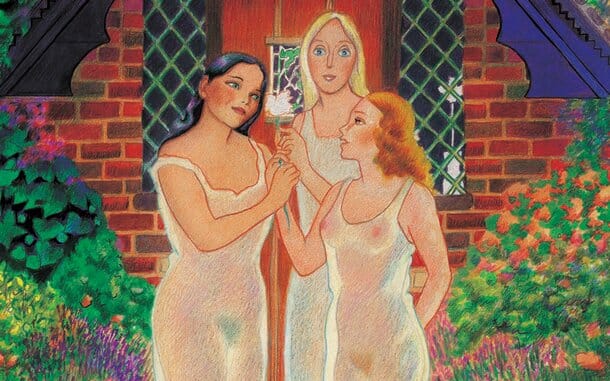

Lost Girls Interior Art by Melinda Gebbie

On the opposite end of the spectrum lies Dorothy Gale, corn-fed farmgirl from the Heartland. Dorothy’s first orgasm comes when a tornado ravages her homestead, and her journey through “Oz” is a succession of sexual encounters with willing farmhands. The Wizard’s revelation here is less Emerald City than Flowers in the Attic.

The grown protagonist of J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, Wendy Darling is stuck somewhere in the middle of these extremes. The green-clad eternal boy of Wendy’s story sneaks into her window one evening and brings her to a life-changing climax while her two preteen brothers watch on, hands moving furiously under their nightgowns. What follows for Wendy is a period of free love quickly crushed by guilt and loss of innocence as a hook-handed man pursues the youths around the Darlings’ upscale home. Rather than cope with her rollercoaster feelings toward sex, Wendy marries an older man for whom she feels no sexual attraction. Their most passionate sex scene in the book takes place entirely without their involvement, as the pair performs mundane tasks that cast fireside shadows posed in carnal positions.

These three women, all of whom titillate each other multiple times throughout the course of the book, find comfort in relaying their tales to one another while sleeping under the same roof in a hotel. It’s not a stretch for readers to connect the dots between erotic encounters and source material, but each story culminates in a splash page that steps out of the tale’s reality to illustrate the allusions of the founding stories. On these pages, Gebbie becomes perhaps the first and only person in the world to draw a great pink vaginal alligator or a clitoral caterpillar awash in opium smoke.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-