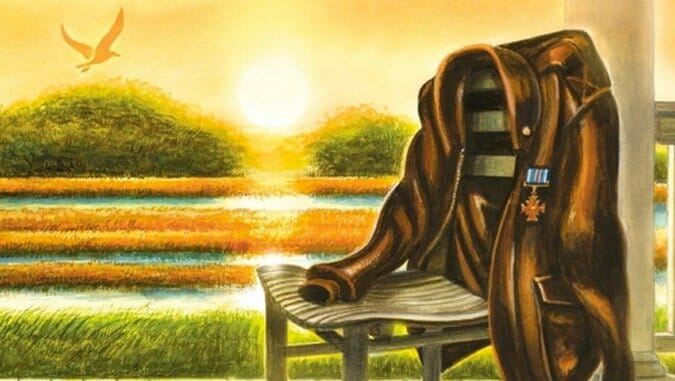

The Death of Santini by Pat Conroy

The father of all battles

What other writer in American literature has gotten more mileage from his own tragic family than Pat Conroy? The author’s army-brat upbringing under a tyrannical Marine Corps father was filled with enough turbulence, pain and insanity to inspire 40 years of literature. None of his books aired the family’s dirty laundry as famously as his 1976 novel, The Great Santini. It’s the story of a Southern family and its brash patriarch, Bull Meecham, a fighter pilot with a healthy ego and an iron fist. In Conroy’s new memoir, The Death of Santini, Bull Meacham is a sweetheart compared to the man who inspired the characters—Pat’s own father, Don Conroy.

“I remember hating him even when I was in diapers,” Pat writes, taking us straight into the lion’s den with stories of the monster’s temper and cunning. Like all great memoirists, Pat has an incredible memory, recalling every harsh word, every beating from childhood, and he conveys these horrors without overtaxing the reader. We get just enough of Don Conroy the bully before Pat shows us how the Santini legend was made.

Don, self-dubbed “the Great Santini” after a flying trapeze artist, was too intense even for fiction. After reading an early draft of The Great Santini, Conroy’s editor at Houghton Mifflin, Anne Barrett, recommended softening Bull to make him more sympathetic for readers. The experience of writing it was so traumatic that Pat spent six months afterwards “bed bug crazy” and sought help from a therapist ahead of the book’s release. “I could not bear to think that I wrote a five-hundred page novel just because I needed to love my father.”

The day the book arrived, his father pronounced, “This may be the best day of my life.” Then he took it home to read and called back two hours later. “Why do you hate me, son?” he asked, declaring it “the shittiest book I’ve ever read.”

Pat fared no better with the rest of the family. His uncle called him “a perverted ingrate,” and his grandfather told him if he wanted to learn to write, he should read James Fenimore Cooper. Uncles and aunts and friends of the family came out of the woodwork to berate him and his false portrait of a saintly tender man. “It occurred to me that there was some uncanny genius at work in my father’s perfection of child and spousal abuse,” Conroy writes. “He did it in the dark, like a roach crossing the kitchen floor at night.”

To Pat, the most heartbreaking critique came from his chief ally, his mother, who branded him a traitor. “Here’s why you really stink as a writer, Pat. You gave that book to him. Let me tell you a secret, son—I ruled that house and everything that went on in it.”

Of course, the book went on to achieve great success. Pat brought his dad to writing conferences and book signings where fans genuflected before his tough-guy charisma. When it was announced that a film of the book would be shot in their hometown of Beaufort, S.C., starring Robert Duvall in the title role, Santini declared, “It’s a shame John Wayne is dead. Only he could’ve brought my virility and toughness to the screen.”

The rest of the book chronicles ever more ugly aspects of family life—the sickness and death, the fights and resentments, the fall-out and tortured legacies. “I don’t believe in happy families,” he writes. “A family is too frail a vessel to contain the risks of all the warring impulses expressed when such a group meets on common ground.”

Pat’s literary side came from his mother, Peg, who grew up among impoverished snake-handling church folk in Alabama. When they were kids, her mom left in search of better opportunities, and they were saved from their deluded holy-rolling father and probable starvation by a family of charitable black sharecroppers. Peg, the chief target of Santini’s foul heart, endured her beatings and gave some in turn, taking her pain out on the daughters, especially the eldest, Carol Ann.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-