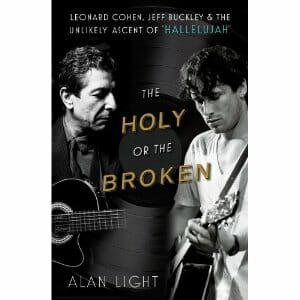

The Holy Or The Broken by Alan Light

A Victory March

The Holy Or The Broken traces the history of a single song—“Hallelujah,” written by Leonard Cohen and originally recorded in 1984, with a chorus that invokes the Messiah and the holiday season and verses about struggles with more worldly desires.

These days, this song can be classified as inescapable, but over most of its lifetime, and through several iterations by famous musicians, it enjoyed surprisingly little favor.

Author Alan Light—who co-wrote Greg Allman’s biography, penned a book on the Beastie Boys and worked as editor-in-chief at Vibe and Spin—follows “Hallelujah” as its lyrics and instrumentation change. He shows how a relatively unknown song can be adopted, enhanced and canonized by the machinery of culture.

Leonard Cohen’s first three albums, released between 1967 and 1971, built on gently picked guitars, string sections and Cohen’s flat, low voice. His lyrics often earned comparison to Bob Dylan’s (Cohen published novels and poetry before moving into music).

When Cohen entered the studio to put together Various Positions in 1984, he hadn’t put out an album since 1979. He brought the results of his recording sessions—“Hallelujah” included—to his label, Columbia, but the label declined to issue an album. So Various Positions came out first overseas.

Initial reviews of the album after release in the U.S. on a smaller label did not mention “Hallelujah.” The original recording of the song has quintessentially ‘80s-sounding drums and a strange echo treatment applied to Cohen’s voice. Cohen claims that during recording, producers tried “… to get it to be a community choir sound, very humble.” He also notes that he wanted to “transcend the dualistic system and reconcile and embrace the wholeness”—hardly a humble goal.

Production efforts settled on a heavy swathe of backing vocals that assist Cohen on the chorus, occasional bursts of powerful electric guitar and the sturdy ballad structure often used in heart-wrenching soul songs. The combination makes “Hallelujah” into a grand, if slightly cheesy, affair.

Cohen purportedly worked on the song’s lyrics for years, whittling them down to four verses from a pool of 80 he had written. (Cohen said of songwriting, “It’s not the siege of Stalingrad. . . but these are tough nuts to crack.”) For those uninitiated in the ways of “Hallelujah,” the chorus of the track consists entirely of repetitions of its title. The verses contain religious references—“I’ve heard there was a secret chord/ That David played, and it pleased the Lord,” though Cohen intended “to indicate that Hallelujah can come out of things that have nothing to do with religion.” Things like watching a woman “bathing on the roof,” before “she tied you to a kitchen chair.”

As soon as Cohen started performing the song live, he changed the lyrics, making it “much darker and more sexual.” Highlights of the new verses include: “but love is not a victory march/ it’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah;” “I remember when I moved in you/ and the holy dove was moving too;” and “Now maybe there’s a God above/ but all I ever learned from love/ is how to shoot at someone who outdrew you.”

In 1991, a Cohen tribute album came together, with artists like R.E.M., Nick Cave and John Cale recording their own renditions of Cohen’s tunes. Cale, with impeccable avant-garde credentials as one of the original members of the Velvet Underground (he also has respected solo albums and an impressive record of production work for the likes of the Stooges, Nico and Patti Smith), chose to record “Hallelujah.” His version took place alone at a piano. It’s a “Hallelujah” on the verge of alienation and despair, if not there already—in Light’s words, Cale’s version comes off “purged of joy.” Cale also changed the verses, taking two of Cohen’s recorded originals, and then adding three of the darker ones from live performances.

The next shot at “Hallelujah” came from Jeff Buckley, the son of ‘60s folk and pop singer Tim Buckley. Young Buckley signed a contract—also with Cohen’s Columbia records—in 1992, after playing all over bars in New York and getting accolades from the likes of Allen Ginsberg. (The famous poet hooted at Buckley in appreciation during a show, but Buckley didn’t understand his intent and told him “you don’t have to be a dick.”)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-