The Master of Confessions by Thierry Cruvellier

Amid the horror that engulfed Southeast Asia in the wartime 1960s and ‘70s, an even more hideous atrocity eventually revealed itself in Cambodia.

The killing fields.

Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge regime of Pol Pot and a secretive, paranoid Communist revolutionary cadre starved to death, worked to death or slaughtered more expeditiously through torture and execution an estimated 2 million men, women and children—roughly a quarter of Cambodia’s entire population.

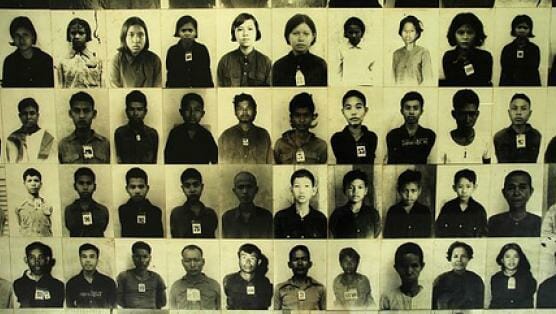

As Cambodia immersed itself in genocide, one institution stood out for exemplary competence and meticulous recordkeeping in the administration of death: the S-21 prison in Phnom Penh. Its faithful party functionary superintendent, responsible for the torture and execution of 12,000 people or more, went by the name Duch.

We have here his strange and appalling story—math teacher turned revolutionary, turned death camp administrator, turned born-again Christian, turned defendant before an international tribunal.

Through the lens of Duch’s trial, Thierry Cruvellier tells of the man’s crimes against humanity. The proceeding began formally in February 2009 and concluded with a guilty verdict the following year. Cruvellier, a friend of this reviewer, has covered every international trial on war crimes and crimes against humanity in recent history: Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Bosnia and Cambodia. As the only journalist to have done so, he holds a unique position for understanding and describing the operation of such courts, from the groundwork laid by impassioned, idealistic human rights activists to the multinational political expediency that inevitably compromises their judicial scope.

Cruvellier’s book examines a microcosm—the specific evidence presented against one man during one trial. We do not see a panoramic view of Cambodian history or even the segment of history consumed by the killing fields. Like the court, Cruvellier concerns himself only with Duch. How does a teacher, an educated man dedicated to the instruction of children, willingly morph into a merciless interrogator? A man who penned this order to his subordinates?

Did not confess. Torture him!

Hit him in the face

We must apply pressure absolutely

Beat them all to death

Smash them to pieces

A mass murderer, particularly one who murders with the blessing of the state, confounds the human capacity to respond. He presents a temptation as well: to categorize him as a “monster,” set apart from other humans. One who willingly does the things Duch did—or runs the gas chamber for the Nazis or facilitates the Great Purge for Stalin or hacks his Rwandan neighbors to death with a machete—must somehow be fundamentally different from the rest of us.

Yet Cruvellier encounters a disturbing truth, revealed repeatedly from Nuremburg on down through the bloody decades: Monstrous things can be done by ordinary people—people much like their victims, much like their judges.

Francois Bizot, a Frenchman who survived imprisonment by Duch in a camp that served as predecessor to S-21, told this to the tribunal:

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-