Awful Movie Aside, the Original Ghost in the Shell Manga Is Still Weird, Great and Neglected

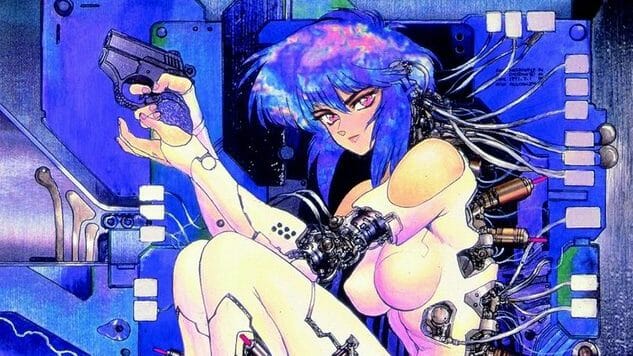

Cover Art by Masamune Shirow

Between 1989 and 1990, Masamune Shirow published a series of 11 comics in the manga magazine Weekly Young Magazine. The series, which would come to be Shirow’s most famous, follows the adventures of Motoko Kusanagi, a major in the Japanese government org, Section 9. The agency, a cross between the CIA and a special ops team, handles delicate national and international military issues. As the comic is set in a cyberpunk future, much of the group’s work involves hackers, cyborgs and technology theft. That serial, Ghost in the Shell, was adapted into an animated film in 1995 by Mamoru Oshii, catapulting the title to the forefront of the then-burgeoning anime and manga scene in North America just as influential anime like Akira, Ninja Scroll and Neon Genesis Evangelion also hit American shores. Released on VHS by Manga Entertainment in 1996, Ghost in the Shell rode this wave of visually inventive and thematically rich anime to classic status. But Ghost in the Shell’s legendary reputation has always been tenuous. It has risen to a prominent position in the public consciousness, and mass awareness of the property has held steady over the last 20 years. But given its attention and the release of the $110 million live-action financial and critical bomb, it’s surprising that the Ghost in the Shell legacy has survived for this long given the first volume’s more complicated critical reception.

Drawn at the height of Shirow’s power, the original Ghost in the Shell manga beautifully combines stylized, expressive figures with fully realized environments. This highly textured world affords Shirow opportunity to detail his neon future full of wires and leather, while leaving room for bawdy slapstick. Readers coming to the manga after the film (either the animated version or the few who saw the recent ScarJo production) may not expect humor to dominate so many scenes, but Shirow’s style, which bridges farcical facial expressions and footnotes where he underlines the lack of realism to his drawing, combines with his kinetic movement and dynamic paneling, offering an evocative experience.

Each issue in the maxiseries is (mostly) self-contained, and the episodic structure allows the series to explore various geopolitical corners of its universe—a quality that’s both a help and a hindrance to its longevity. It lacks a unifying arc but features characters who grow and evolve over numerous stories. This structure is not uncommon for Shirow, and the series closely resembles his other works, specifically the Appleseed series.

Shirow followed up his original story with additional chapters, collected in Ghost in the Shell 2: Man-Machine Interface in 2001 and Ghost in the Shell 1.5: Human-Error Processor in 2003, but these volumes (Man-Machine Interface in particular) feature a lower, and, um, greasier quality of artwork and more prurient narrative interests. That’s not say his original series was chaste—it feature a fairly explicit orgiastic sex scene with the Major and a pair of women—but these aspects became the focal point rather than context in the sequels. Man-Machine Interface, for example, spotlights an alarming amount of crotch and upskirt shots. In this perfect example, Shirow, aware of his objectifying gaze, justifies his frequent inclusion of panties on robot characters. The cartoonist also began to rely on digital tools, and his art took on a grotesquely plasticine look, even for a book about robots. In the essay series The Major’s Body, which details the evolving constructions of Major Kusanagi, critic Claire Napier explains, “This is not labelled as a fetish comic. It is a fetish comic.” Unfortunately, Shirow’s fetishistic tendencies overshadowed his legitimate prowess as a cartoonist.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-