Cartoonist Jim Woodring Talks Poochytown, Hallucinations & Los Angeles in the ‘60s

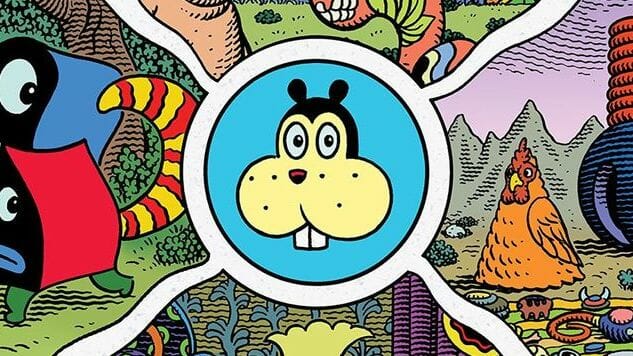

Art by Jim Woodring

Jim Woodring’s visionary art (his term, as evidenced by his website, which promises “visionary art for adventurous spirits,” but an accurate one) is effortful to produce and effortless to consume. Unlike most comics that draw on psychedelic imagery, its narrative line is oddly clear, especially considering that it uses little to no verbal language. Frank—his appetite-driven, buck-toothed, cat-faced humanoid protagonist—is a sort of Candide-like figure, stumbling through a world that mostly seeks to demoralize and consume him. Bold with frills and curlicues, it manages to convey the dangers of both humanity and nature, both as crystalline and as packed with ephemera as William Hogarth’s 18th-century prints but lacking their moral instruction. The result is something timeless and broadly appealing. Poochytown, his latest creation, out now from Fantagraphics, contains a surprisingly gentle message about coming to understand our neighbors and those folks with whom we are thrown together against our will. We are all human, even those of us who are not. Woodring answered our questions over email, including some explanation of his process and those works of art that inspire him most.

![]()

Poochytown Cover Art by Jim Woodring

Paste: Talk to me about how you plan out your books (or if you do). Because they don’t really have words in them, do you write out a narrative first? Or just let it flow?

Jim Woodring: One of the reasons I’ve done so many Frank stories and drawings compared to other sorts of comics and pictures is that from the beginning they have come to me almost as if dictated. The writing process consists of going to a quiet place and writing down the ideas as they present themselves.

I know which ideas are keepers because they come with a certain invisible glow. These crypto-luminous ideas accrue without any thought on my part about what they or the resultant story represents; sometimes the meaning is obvious, sometimes hopelessly obscure—to me, anyway.

Over time, as the characters have increased in number and more territory has been revealed, I realized that the place where the stories are set—The Unifactor—was calling the shots and setting the agenda. Logically I know the Unifactor exists in me, but it doesn’t feel that way. It operates as an entity entirely separate from my conscious self.

I know that all this sounds hopelessly arch and contrived, but it’s the truth.

Paste: When do your most luminous ideas tend to come to you? Are there things you do that help facilitate them? (For example, I know you meditate. Does that help? Or is that more about putting a damper on all the ideas?)

Woodring: One thing that makes this kind of work worth the effort is the privilege of being able to play at the water’s edge. Every other job I’ve had required me to delve deeper into the madness of the world; this one demands I look elsewhere. I like the simplicity of the tools. Taking a pencil and a composition book to a quiet spot and exploring your own mind, bringing fragments of unconscious systems to the surface for repurposing as art… It’s such a real thing to do. Meditation definitely helps; if nothing else it strengthens the ability to concentrate.

Paste: How much thinking do you do about clarity? One of the things that’s always impressed me about your work is how easy it is to follow what’s going on.

Woodring: Once the storyline is in hand, the stories are planned out to a fare-thee-well with clarity foremost in mind. Because the stories are wordless it’s necessary to go the extra hundred miles to make sure everything is easy to understand and follow…superficially, anyway. It’s so much easier when you can have a little panel header that says, “Next Morning….” In the Frank stories, it’s necessary to show the landscape change from night to dawn.

Paste: Again because they’re wordless, your books tend to be very synesthetic. Is that just a cause of the way you’ve chosen to make work or do you experience synesthesia yourself?

Woodring: No, I’m not synesthetic in any way. I wonder what that must be like. The Frank stories are wordless because they’re meant to be beyond time or place.

Paste: You were born in California, right? Have you spent your whole life there? How has it shaped you?

Woodring: I grew up in Los Angeles but have lived in and near Seattle for the past 30 or so years. Yes, growing up in California affected me profoundly, in a good way. It was glorious, really.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-