Stories Within Stories Within History: Talking MeZolith with Ben Haggarty

Ben Haggarty has explored the range of storytelling through both performance at London’s Barbican and Soho theaters and graphic novels; MeZolith, a collaboration with artist Adam Brockbank (a concept artist on the Captain America and Harry Potter films), traces the life of an adolescent in prehistoric Britain as he comes of age. The first volume is structured around various stories told to the young man by the members of his community: some familiar folktales, others strange and unusual—a glimpse into an unfamiliar world.

Originally published in weekly installments throughout the English DFC anthology and Random House in 2010, MeZolith straddles the comfortable and primordial, and in back in print through Archaia/BOOM! this week. The creation of MeZolith combines Haggarty’s own interests as a storyteller with an immersive dive into history. We spoke with the author to learn about the graphic novel’s origins, how archaeological discoveries influenced the book and what the forthcoming second volume will hold.![]()

Paste: What first attracted you to telling stories set in prehistoric Britain?

Ben Haggarty: As a professional storyteller working with oral tradition and performance, I have had to study folktales, fairy tales myths and epics from all over the world. Seeing similarities between stories told in very diverse cultures, and at very different epochs, a question began to burn about the nature of the oldest stories told on British soil. I wanted to dig into the archaeology of imagination—were there stories still being told here today that were once common to all of humanity? The realization that Britain had only become an island separated from the rest of the European continent about 8,000 years ago added to my wondering about who those early ancestors living in pre-insular Britain were. What were their lives like? How did they understand their place in the world? To that end, I seriously researched the Mesolithic Period (circa 12,000 – 6,000 BC) and the lives of the last hunter-gatherers in Northern Europe, before the Neolithic agricultural revolution swept up into Europe from what is now the Middle East. When Adam invited me in 2007 to collaborate with him in making a comic, I proposed a Stone Age horror strip which would allow me to give form to my conjectural ideas about our ancestors and the oldest stories.

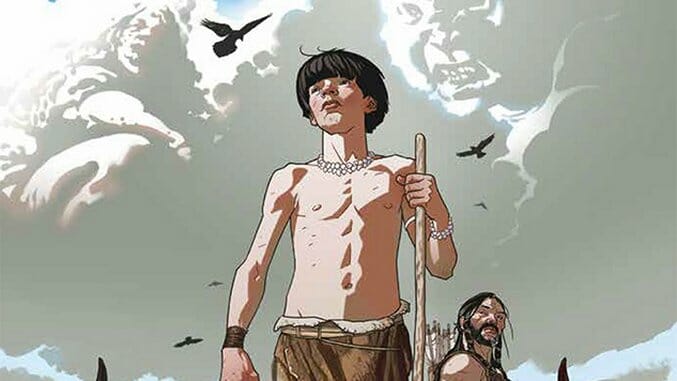

MezoLith Vol. 1 Interior Art by Adam Brockbank

Paste: Your background is in performance storytelling. What first drew you to the medium of comics? Do you find parallels between the two methods of storytelling?

Haggarty: All the narrative arts—from cinema and theater to graphic novels and written word—can be called storytelling; however, my medium is the primary storytelling medium: the spoken word of the oral tradition. It is as old as speech itself. However, the most important and commonly shared tool used in these differing narrative media is the storyteller’s imagination. My initial training was in visual theatre. I worked with mime, puppets and masks and was an apprentice image maker to a legendary British experimental theater company called Welfare State, a somewhat equivalent of the American Bread and Puppet Theater. We had to explore how to tell stories by “showing” them and using as few words as possible. Ironically, as a performance storyteller, I now mainly use words, gesture and displacement to tell my tales. But behind that communicative language is a highly constructed visual narrative, based on an economical language of pictures. I call my sort of storytelling “poor man’s cinema.”

Working with actual physical images is in fact part of an ancient globalwide tradition of performative picture storytelling, which predates literacy. Perhaps the most well-known of these still extant traditions is Japanese Kamishibai (whose master exponents are the incredible Spice Arthur 702). I had also already worked a lot with picture storytelling as a sideline, so, as a lifetime fan of comics and figurative illustration, it was not too far a leap into exploring the comics medium with Adam. Originally, I wanted us to tell the stories without using any words or speech bubbles, but eventually, page constraint meant we had to yield to dialogue.

Paste: What was your research process like for MeZolith, in terms of the history, the geography and the plant and animal life?

Haggarty: I did masses of research—archaeological, ethnographic and anthropological; reading books, visiting museums and speaking with archaeologists. In order to arrive at which stories to tell, I had to understand what the conditions of life were and what the food sources and natural cycles were, which is why the book starts immediately with a bull hunt and the frame story follows a year of changing seasons.

MezoLith Vol. 1 Interior Art by Adam Brockbank

But specific archaeological evidence was the main guide; for example, the image of the woman and her baby buried on a swan’s wing (page 61, panel 6), comes from an actual Mesolithic burial excavated at Vedbaek in Denmark. When I first discovered that extraordinary image, it immediately suggested we should adapt the archaic and internationally widespread swan maiden story and use it for the central story of the collection.

The largest Mesolithic site in Britain is in North East Yorkshire at a place called Star Carr—this gave us a location. We settled on a tribal region of about 30 miles diameter, which is roughly now the North York Moors National Park, ranging from the eastern coast at Whitby and Scarborough (except 10,000 years ago the sea level was 50 meters lower, so both towns with their famous cliffs would have been inland) to the Cleveland Hills in the west. The famous antler headdresses found at Star Carr are glimpsed in the story.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-