Two words of advice for anyone who buys a ticket to April and the Extraordinary World: Buckle up. Keeping real life global history straight in narratives that leapfrog across decades and centuries is tough enough—making sense of alternate history when it’s articulated at breakneck speed throughout multiple eras of European cultural advancement is just downright strenuous. Think of April and the Extraordinary World as an intense workout for your brain, or perhaps your wrist, assuming you’re the type to notate while watching movies. The film shapes a surrogate Earth in the span of mere minutes and fires off salvos of detail, visual and aural alike, in the pursuit of recalibrating the past. The inattentive and unimaginative need not apply.

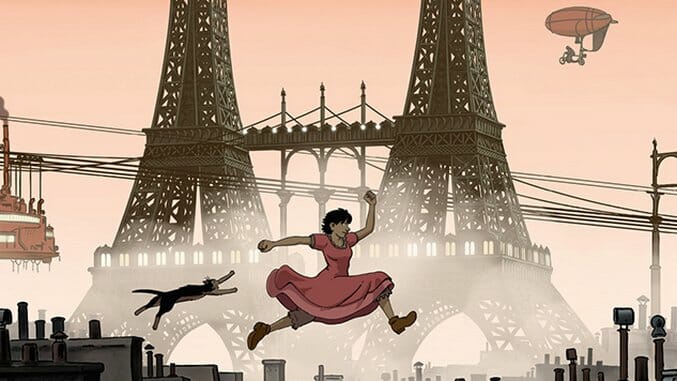

Good news for diligent viewing types, though: April and the Extraordinary World is pretty great, a compact exercise in world building without handholding that rewards a patient, observant audience. If you can keep pace with the film’s plot deployment, you’ll be in for a wonderful ride littered with talking cats, fabulous steampunk backdrops, rollercoaster excitement and terrific characters, all drawn through the fundamental beauty of cel animation. April and the Extraordinary World’s style feels like an appropriate antiquity taken in line with its basic conceit, which is complicated enough to make easy summarization totally futile.

But let’s give it a try anyways. The film supposes a timeline in which Napoleon died in an 1870 chemical explosion on the eve of the Franco-Prussian war, a turn of events that eventually leads to the mysterious disappearances of Europe’s best scientists and inventors, which itself leads to a halt in technological innovation and sparks a war of resources between the French Empire and the Americas. To win the war, France starts rounding up rogue scientists and forcing them to work in service to the Empire, and thus we are introduced to the Franklin family: grandpa Prosper (Jean Rochefort), father Paul (Olivier Gourmet), mother Annette (Macha Grenon) and their daughter April (Marion Cotillard), who are clandestinely working on a serum to cure illness and even repel death itself.

Try saying all of that in one breath. You’ll probably pass out face-first on the floor—but guess what? That little synopsis only sets up April and the Extraordinary World’s first 20 minutes. The film doesn’t begin in earnest until we meet April as a teenager in 1941, separated from her family for ten long years following a chase sequence that makes up the bulk of April and the Extraordinary World’s prologue. Directors Christian Desmares and Franck Ekinci’s story commences as April attempts to reproduce the serum her parents perfected a decade prior, which of course leads her on yet more chases and yet more thrilling exploits. Saying more than that threatens to give either too much or too little away, depending, so all details thus divulged will have to suffice.

Yet if April and the Extraordinary World’s temporal scale is impossible to distill into a paragraph-length capsule, it is also the film’s greatest strength. You get the sense that with each moment of spectacle and each sequence of thrilling adventure, Desmares and Ekinci are merely stretching out their legs, enjoying the vast and comfortable artistic space they have created for themselves and for their characters. They’re in no hurry to get anywhere, though the fundamental brio with which they structure the picture from top to bottom suggests otherwise. April and the Extraordinary World is a movie defined by urgency, but it is also disciplined enough not to trip over itself rushing to get from point A to point B.

That combination of verve and storytelling economy lends April and the Extraordinary World a density that is further increased by its plethora of themes: the need for invention and scientific enterprise; the propaganda-fueled governance of nationalism; the dangers of ambition; not to mention a minor pro-conservation treatise. April’s existence is ordered by authoritative zealots and the very air she breathes is probably composed more of smoke than of actual oxygen. Her poor cat, Darwin (French singer Philippe Katerine), is on his deathbed when we meet him, hacking and coughing up a storm (thanks to black lung) in between lamentations that he’ll never get to see Rome. The message isn’t exactly subtle—Down with fossil fuels! Up with renewable energy!—but it’s also all part of the fabric the film is woven out of, and so we never for a moment feel that Desmares and Ekinci are preaching at us.

They’ve chosen their fabric well, too. Ekinci worked as a storyboard artist on The Adventures of Tintin, which ran on HBO back in the early 1990s, and you can immediately see the influence of Hergé on April and the Extraordinary World’s look and texture. (Weirdly, it also calls to mind Kazuaki Kiriya’s Cassherin. Just watch the film and it’ll make sense.) The palette is darker, for obvious reasons, but the lines are just as soft and the characters maintain a sort of elasticity that abets their emotionalism while simultaneously supporting their comic qualities. It’s a beautiful film that reminds us of the aesthetic value of traditional animation and the necessity of human ingenuity, all without treating its audience like idiots. That might seem like a minor plus, but any animated effort as heady as April and the Extraordinary World deserves bonus points for acknowledging its patrons’ intelligence.

Directors: Christian Desmares, Franck Ekinci

Writer: Franck Ekinci, Benjamin Legrand

Starring: Marion Cotillard, Marc-André Grondin, Jean Rochefort, Olivier Gourmet, Macha Grenon, Philippe Katerine

Release Date: March 25, 2016

Boston-based critic Andy Crump has been writing online about film since 2009, and has contributed to Paste Magazine since 2013. He also writes for Screen Rant, Movie Mezzanine and Birth.Movies.Death. You can follow him on Twitter and find his collected writing at his personal blog. He is composed of roughly 65% craft beer.