The Scintillating Screwball Shenanigans of Intolerable Cruelty

Miles Massey. Donovan Donaly. Rex Rexroth. Freddy Bender. Sarah Batista O’Flanagan Sorkin. Wheezy Joe. Romana Barcelona. Heinz, the Baron Krauss von Espy. These are the names of just a handful of the colorful characters populating the world of divorce lawyers, gotcha journalists, Hollywood hacks and gold-digging hustlers we meet in Joel and Ethan Coen’s 2003 screwball comedy Intolerable Cruelty. Generally seen as a lesser work in the canon of two of our finest American directors, the 20 years since its release allows us to look back with greater clarity on the pure venom that seeps into this wonderfully wicked lark that takes a genre in its heyday and subverts the ever-loving heck out of it.

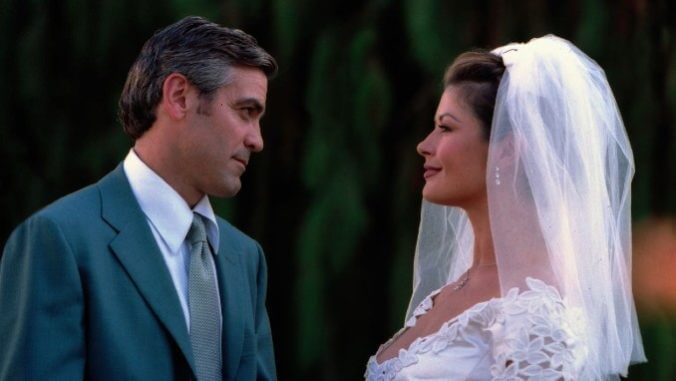

Intolerable Cruelty was marketed as any other run-of-the-mill romantic comedy hitting the multiplex in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s starring some variation of Reese Witherspoon, Hugh Grant or Julia Roberts battling it out with their contentious co-star before finally realizing they were made for each other all along. One look at the poster, with its picturesque white background framing George Clooney smirking down at Catherine Zeta-Jones, with taglines above and below them—one saying “Engage the enemy” and the other “A romantic comedy with bite”—tells you everything you need to know about the audience Universal Pictures was trying to bring in for this.

Those viewers by and large rejected it. This is no surprise, as Sweet Home Alabama and Maid in Manhattan this picture isn’t. A razor-sharp satire from two of our most irreverent comedians, Intolerable Cruelty takes an ax to the modern rom-com by making us root against the very idea of love in this cynical, sinister world where the only gesture more romantic than signing a prenup to ensure you aren’t after your partner’s millions is for your spouse to rip that prenup to shreds because they trust you…allowing you the ultimate prize of taking them for at least half of everything they’ve got. Audiences rewarded this $60 million-budgeted picture (still the highest budget for a Coens’ film to date) with a paltry $35 million domestic box office—though its star power helped give it a little bounce back overseas for a $120 million worldwide total

What’s more unfortunate is how the critical community, those who had spent the better part of the previous 20 years crowning the Coens as two of the elite, also balked at this one. While it wasn’t a full-on disaster, the bloom unquestionably fell off the rose before the following year’s The Ladykillers, giving them a perceived slump before they bounced back with Best Picture winner No Country for Old Men. The disappointment of Intolerable Cruelty was largely chalked up to the feeling that the filmmakers were trading too much in precisely what the marketing was trying to sell us—that the genius minds behind Fargo and Barton Fink had sold out to give us a mainstream studio picture for the first time, and that their sensibilities clashed with the product.

This perception represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the cold, exacting dagger that Intolerable Cruelty drives through the heart of romance—gleefully smiling the entire time it does so. Indeed, the brothers didn’t originally intend for Intolerable Cruelty to be a picture they would direct. In the ‘90s, they took a job doing a pass on the script, which had been moving its way through the studio from hands including John Romano, Robert Ramsey and Matthew Stone, and even Carrie Fisher. It was a for-hire gig and the Coens moved on from it, only coming back around once their recent collaborator Clooney got his hands on their version of the script and wanted to bring them in to direct, with Zeta-Jones as his screen partner. While that could make you believe that the Coens didn’t have their heart in this one, Intolerable Cruelty is unmistakably a product of their delectably despicable minds as they put their characters through all manner of hell.

The crux of the story revolves around Miles Massey (Clooney), a marital attorney responsible for the famed and allegedly impenetrable “Massey prenup,” and his burgeoning feelings for Marilyn Rexroth (Zeta-Jones), a career divorcee whose most recent attempt at conning a man out of his fortune has fallen flat on its face thanks to Massey’s legal defense of her husband. These are two people who seemingly have no respect for the sanctity of marriage, nor even the purity of love, and their draw towards one another flies in the face of everything they’ve come to believe about the world and their identities.

“They both don’t really realize the trouble they’re in emotionally until they run into each other,” Clooney said of Miles and Marilyn. “They’re both romantics in this horrible, screwed-up life that they live.” While the ultimate destination of Intolerable Cruelty may be easy to predict from one glance at the poster, the wicked charms come in the journey to get there.

Per Clooney, “We all know the ending of a romantic comedy, that’s the toughest thing to do… and the truth is: that’s why actors don’t really do them that often anymore because it’s very hard to do a romantic comedy and go, ‘Hey, surprise! They’re going to get together!’ but here the journey was more interesting and a little darker.”

“A little darker” is putting it mildly. The depths these two go to retain the upper hand are as extreme as putting out a hit on one another, fully plunging us from screwball antics into straight-up noir. That sensibility is reflected in the doom and gloom that laces through Roger Deakins’ foreboding cinematography and Carter Burwell’s stomach-churning score, no better on display than in the scenes where Massey pays a visit to his boss Herb Myerson (Tom Aldredge), who treats Massey to sermons from his dark, dimly lit office where he’s strapped to the nines with wires and medical equipment, with magazines in his waiting room like “Living Without Intestines.” Herb is the ghost of Miles’ future if he stays on his current path, just like Marilyn’s frequently divorced and exorbitantly wealthy single friend Sarah who only has “a peptic ulcer to keep her warm at night.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-