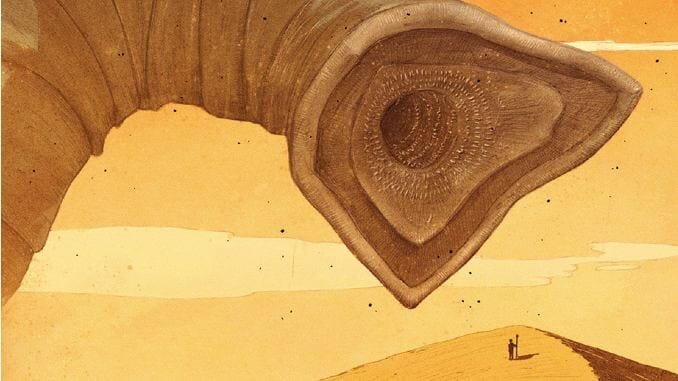

David Lynch’s Dune Might Not Be Perfect, but Its New 4K Restoration Reminds Us It’s Admirable

Does a home media release require a thesis statement? Do boutique and specialty home media labels need a good, compelling argument for securing the rights to add a movie to their library? “People who like this film should be able to own a copy themselves” seems like reason enough to feed physical and digital libraries, but Arrow Video’s new 4K treatment of 1984’s Dune makes an implicit plea of its director, David Lynch: Break the 37 year silence and talk about the film.

Lynch has famously declined opportunities to produce a director’s cut of Dune and, perhaps even more famously, shies away from discussing his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s massive, influential 1965 science fiction epic in interviews. Speaking to the former point on the 4K’s Deleted Scenes feature, producer Raffaella De Laurentiis, the daughter of the film’s legendary executive producer Dino De Laurentiis, mentions the sticky claim that “there was a four-hour version of the movie edited by David Lynch, but that never really happened.” There was an assembly cut, a concept that’s foreign to an astounding number of people in 2021: That’s the first cut, where every bit of usable footage is strung together by the editor (in this case Antony Gibbs) into watchable shape and subsequently trimmed into a more watchable shape.

Whenever a DCEU or MCU movie is reported as having an uncut four-hour runtime, fans go a-frothing to Twitter demanding the full “director’s cut,” unaware that this is simply how movies are made. Dune met with no such fervor in 1984, and no such fervor exists today. The version we have is more or less the only version there is, save for a 186-minute cut that aired on TV in 1988 which Lynch disavowed for how brutishly it handled his original vision: It credits Alan Smithee for direction and Judas Booth for the script. Between that and the stories of what went into the film’s production, it’s little wonder why Lynch is reluctant to open up about it. Dune is a towering pile of imperfection, the end result of years of work—nightmarish, hard work that critics and audiences rejected (at best) and disdained (at worst) when it premiered.

Almost four decades later, Lynch, who arguably walked so that John Harrison could run in his 2000 Sci-Fi Channel miniseries, Frank Herbert’s Dune and so that vaunted French Canadian auteur Denis Villeneuve could reportedly soar in his own forthcoming adaptation, deserves reconsideration for what he achieved in bringing Dune to life. That’s the heart of the Arrow set: Not simply presenting the movie in a breathtaking restoration, though this is absolutely the set’s highest prize, but digging through the past to learn how the movie was made from the people who made it, and how it was received by people who were around either to receive it or witness its reception.

“When David Lynch got Dune, I think it was generally perceived that he got it because he was coming off the success of The Elephant Man,” explains critic David Ansen in Impressions of Dune, a 40-minute 2003 documentary that’s included in the package, “which in turn was a big surprise to Lynch fans because before that, all he’d done was this very strange cult underground movie Eraserhead.”

Ansen is talking about Dune as an inherent risk, despite its relationship to preexisting IP, for practical and logistical reasons. Lynch, his new success aside, was a risk for the project; IP aside, reimagining Herbert’s dense, labyrinthine book as cinema was a risk, too. But Ansen frames neither as negative. Instead, he praises De Laurentiis for taking the risk in the first place, and that praise resonates through 2021. Major studios today are wary of bankrolling anything aside from that attached to preexisting IP, movies that pose not so much a risk but an upside-only gamble for their bottom line. Reliance on IP for big-screen inspiration isn’t a new practice, but it’s considerably more widespread today than it was in the 1980s. Comic book films dominate moviegoing culture still, even in COVID times: The pandemic delayed the releases of Black Widow and Shang-Chi, but the association Marvel’s streaming series’ share with the movies have helped the brand stay visible for the last year. Shang-Chi, for its part, is already looking like a hit. In non-comic viewing, the rash of live-action takes on Disney classics and theme park rides has spread with movies like Cruella and Jungle Cruise.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-