The Two Faces of January

In The Two Faces of January, the latest adaptation of a Patricia Highsmith novel, you’re not only seduced by the characters but also by the décor, the mood, the swirl of cigarette smoke and the stylishness of the sunglasses. Whether it’s Alberto Iglesias’s score, meant to evoke the icy paranoia of Bernard Herrmann’s music for Alfred Hitchcock, or the period setting, the feature directorial debut of Oscar-nominated screenwriter Hossein Amini revels in its old-fashioned tone. The Two Faces of January is a thriller in love with the tense, sly thrillers of yesteryear.

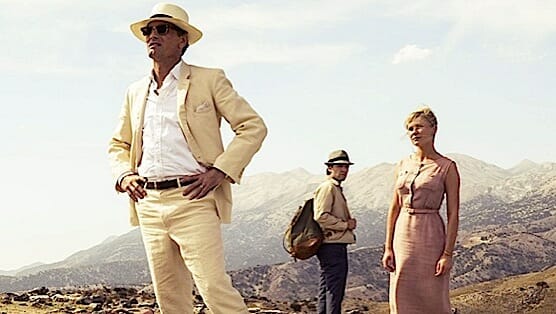

Set mostly in Greece in 1962, the film stars Viggo Mortensen and Kirsten Dunst as Chester and Colette, an American married couple vacationing in Athens, who meet Rydal, an American tour guide who offers to show them around the city. (That he’s also a con man is a fact he conveniently forgets to mention, overestimating the exchange rate between drachmas and U.S. dollars for his benefit while negotiating purchases for his customers.)

For those familiar with Highsmith’s work—which has been adapted for films such as The Talented Mr. Ripley and Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train—The Two Faces of January’s opening sets us up for the inevitable unsheathing of the knife as Rydal prepares to bilk this unassuming couple. (Adding to the story’s psychological heft, when Rydal first lays eyes on the older Chester, he confesses that he’s struck by how much he looks like the tour guide’s recently deceased father, a spectral figure with whom he had a difficult relationship.) But the setup doesn’t dictate the direction forward: Chester is a successful investor who, it turns out, is being tracked by a private investigator on behalf of some enraged clients. When Chester accidentally kills the investigator, he has no choice but to rely on Rydal to help ferry him and his wife back into America before the police descend on them.

The characters’ chic, vintage outfits—all smart suits and lovely summer dresses—give The Two Faces of January an agreeably retro appeal, but the nostalgic quality extends beyond that. Amini (who adapted The Wings of the Dove and Drive) relishes the story’s pre-Internet milieu, which allows for a pleasurably leisurely sense of tension. (The private investigator’s death lingers over the proceedings through radio reports and newspaper headlines as our three main characters travel by buses and boats in the hopes of staying a step ahead of the authorities.) That lack of white-knuckle intensity is deceptive, however: Rydal, Chester and Colette are trapped together in their bubble of mutual distrust, never quite knowing how close their pursuers are while simultaneously wondering what each other’s ulterior motives might be.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-