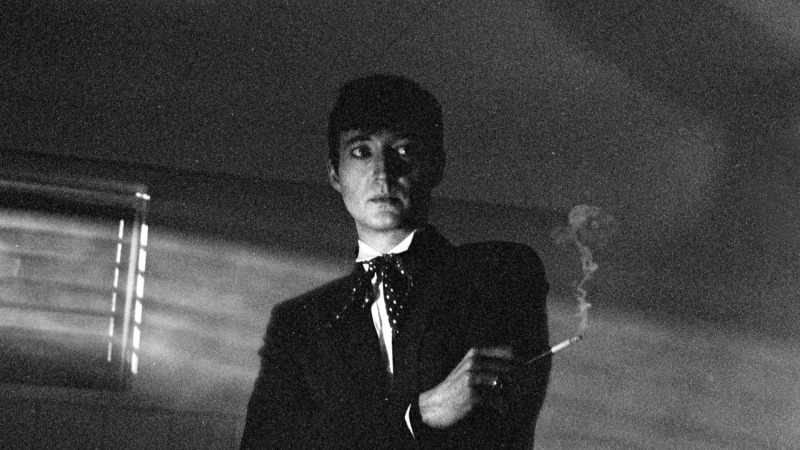

Art d’Ecco Weaves a Metaphysical Pop Tale on Serene Demon

Serene Demon is simply an enjoyable album to listen to, its vast textural content creating a baroque funhouse of sound.

“I’m on the inside reaching out,” Art d’Ecco whispers during the chorus of “Shell Shock,” the ninth track on the enigmatic Canadian glam rocker’s newest album Serene Demon. Sung from the perspective of a lucid state, the verse acts like an impromptu thesis for the project, one where the already unconventional artist weaves an even more striking, all-embracing picture of his clashing opinions about life itself. How can something as awful as a demon appear so cloudless and bright? d’Ecco not only tackles the multi-faceted concept of evil, but accepts how it makes him feel trapped at times—trying to assemble something, anything, out of the agonizing fear and hopelessness.

When describing the music that d’Ecco and artists of a similar fervor create, the go-to buzzword phrases are usually along the lines of “idiosyncratic” or “left-of-field.” But these terms alone would barely scrape the surface of Serene Demon, d’Ecco’s fifth release, a record that borrows sounds and motifs from years of pop history—similar to Cindy Lee—and blends them into a wondrous world of eccentric bliss. There’s moments of off-kilter 2010s indie twee—where d’Ecco’s already wispy voice waivers like Deerhunter’s Bradford Cox—slick ‘80s Hall and Oates-style coolness, winding ‘70s disco and even traces of ‘60s psych-folk. With a staggering list of inspirations and comparisons, d’Ecco doesn’t limit himself to making an album that sounds like just one of them. Instead, he seamlessly jumps from one idea to another as Serene Demon plays on, the result being a work that finds the balance between zany busyness and sharp-eyed focus.

Over 30 musicians contributed to Serene Demon, whose identities are continuously revealed as the album goes on. They come in waves—from the stark saxophone that wails during the dissent of “True Believer” to the cowbell taps that skitter in the beginning of “Tree of Life”—and add even more theatrical flair to d’Ecco’s ambitious vocal performance. He approaches the album’s lyrics with an acute awareness of his mortal limitations, and how happiness—which he paints as a fleeting character—can either enhance or diminish the human experience. It’s a philosophical album, most outwardly shown by the reference to Albert Camus’ The Stranger on the sprawling, instrumental track “Meursault’s Walk,” and doesn’t shy away from asking uncomfortable, almost impossible queries. “Are you dealing with the pain now?” he shakily interrogates on “Survival of the Fittest,” in a frantic tone that makes the question seem like a challenge. “Only the strong will survive,” he declares shortly after, like a leading voice at the end of times who’s trying to make peace with that sentiment himself.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-