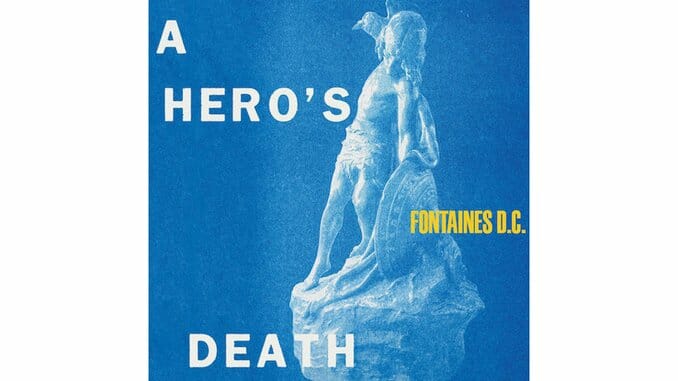

Fontaines D.C. Completely Transform on A Hero’s Death

The Irish band’s quick follow-up album mines maturity from far darker sounds

Last year, five Irish twenty-somethings became one of the most exciting rock bands on the planet. Their debut album Dogrel opened with a cymbal-clattering tune that repeatedly pontificated, “My childhood was small, but I’m gonna be big!” By industry standards, Fontaines D.C. are hardly a “big” band, but after just one album, they were already set to headline London’s Alexandra Palace—a massive 10,000 capacity venue hardly ever headlined by rising artists—plus they were booked by some of the world’s biggest music festivals: Coachella, Glastonbury, Primavera Sound and SXSW. They even toured America with IDLES.

Though rock bands occasionally work their way up the industry ladder in a similar manner, not many also do so with universal critical acclaim. Fontaines D.C. received widespread praise and a Mercury Prize nomination for their gritty-yet-uplifting, literary-inspired rock tunes, which spanned post-punk, surf and classic rock ‘n’ roll. Frontman Grian Chatten was a force, speak-singing his way through songs that were just as fun as they were poignant. Dogrel was a celebration of Dublin and the things that make it both colorful and grey: the drunken cabbies, “the bruised and beat up open sky,” the gold harps, the churches and, most importantly, the dreamers and the underdogs. It’s clear the band saw themselves as such, and whether or not their working class image is exactly what it’s cracked up to be, you can’t accuse them of slacking—that’s for sure.

Quickly after Dogrel’s release, they began work on its follow-up A Hero’s Death. It’s hard for rock bands to build up the same amount of attention for their second album, especially with a group that embraces styles of the past, but Fontaines D.C. chose an approach that many artists would find unthinkable—they deliberately attempted to destroy listeners’ original impression of the band.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-