The Eternal Sunshine of Jenny Lewis

The singer/songwriter talks about taking Beck’s songwriting challenge, becoming a rockstar because of Kim Deal, collaborating with the magnetic presence of Jon Brion and how her latest triumph, Joy’All, helped her shed the weight of grief.

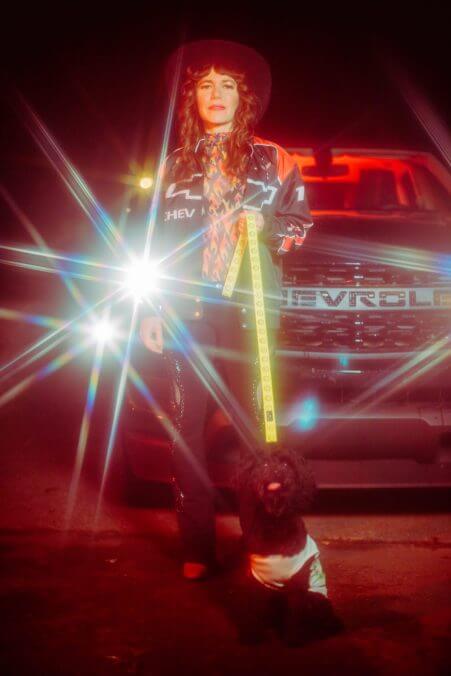

Photos by Bobbi Rich

Next year, I’ll be celebrating the 20th anniversary of Rilo Kiley’s More Adventurous—an album that, in no short terms, saved my life once upon a time ago. The title track, which has taken many shapes in my soul over the last 10 years, is one of immense and unshakable perfection; its chaotic and doleful architecture has lent itself to my sorrow over and over again. “And if I get banished from the kingdom up above / I’d sacrifice money and heaven, all for love / Let me be loved, let me be loved,” Jenny Lewis sang in the second verse of “More Adventurous,” and those lines have stuck with me. There’s a simplicity and benevolence in wanting to be desired by another body here on Earth; when I went through any of my many heartbreaks, there “More Adventurous” was to soften the ache. Flash forward 19 years or so, and Lewis is again examining how she might begin pulling love through the barricades of grief—this time on Joy’All, her fifth solo album in 17 years and a kaleidoscopic pivot of the grandest proportions.

Last month, I spent some time with Lewis via Zoom. It was a pretty last minute affair on a Friday afternoon, but to be on a call of any kind with her is an immeasurable rapture that 15-year-old me would be in shambles about (25-year-old me is, too, to be honest). From her Los Angeles homestead, she tells me I look like Leonardo DiCaprio in The Basketball Diaries—and I (and my ego) take her word for it, given that she spent a lot of time with him while filming Don’s Plum in the mid-nineties. Given how close to the spotlight she’s always been, and the gravitational magnitude of the music she makes, it’s easy to forget that Lewis is a rockstar immune to generational separation. Whether it’s taking roles in classic sitcoms like The Golden Girls, Mr. Belvedere and Growing Pains, fronting the incomparable alt-rock band Rilo Kiley or opening for Harry Styles on his Love On Tour dates in 2021, she’s continuously putting herself in the eyes of the zeitgeist. At the same time, she’s also been unveiling cornerstone records. Everything from The Execution of All Things in 2002 to On the Line in 2019 has found a niche in our hearts.

On the Line felt like a real achievement in so many ways. It was there that Lewis embellished her own storytelling prowess to the utmost degree. She chronicled everything from arguing about Elliot Smith and grenadine with a narcoleptic poet from Duluth to drinking Beaujolais wine and reminiscing about the past while kids play on a slip ‘n’ slide nearby. The album arrived to instant—and earned—critical acclaim and was her best work yet, but its cycle was cut short by COVID a year later. “[On the Line] had blue balls, to put it frankly, by the time we were cooking,” Lewis says, laughing. “Usually you tour something for two years, a year-and-a-half. We were in the groove and then the world shut down.” What came next was a familiar breakthrough of mourning, as the canceled tour and subsequent quarantine forced Lewis to slow down and process grief she’d turned off while on the road: In 2017, she reunited with her estranged, ailing mother after 20 years (who passed away before On the Line came out) and saw her longtime relationship with Johnathan Rice come to an end.

“The culmination of all of that—losing my mom, losing my dad before that, losing my rock ‘n’ roll dad Gary Burden, leaving my relationship of 12 years, going to New York for the first time and leaving LA—really caught up with me in 2020. And not having the distraction of going on tour, which is just the ultimate excuse to be a deadbeat and not get back to people and just run. My dad, he was a touring musician. He started three or four families and never stopped, because he was just on the road. His entire life was touring the world. I think I was following in that tradition of ‘just go, go, go.’ Then, once I stopped, everything was still there. I didn’t really have time to grieve, because I was on the road when that happened, so it all caught up with me in a really positive way, ultimately,” Lewis says.

The next chapter truly started with “Puppy and a Truck,” which saw Lewis really considering the weight of her own mortality and humanity. (“My forties are kicking my ass,” she croons at the beginning.) The song was released last year, but she’d been teasing it during the opening sets from her tour with Styles (who cameos dressed like a puppy in the music video) well before Joy’All was announced. I ask Lewis if the pandemic opened the door for her to find closure with losing her mom and going through a long-term breakup, but she rejects that term and replaces it with her own: “Opensure.” “I think it’s an openness to the reality of being a human being—as you age—and these things just happen,” she adds. “And that was the first time I’d ever been alone.” When Lewis laments “I’m 44 in 2020 and thank God I saved up some money / Time to ruminate like, ‘What the fuck was that?,” there’s a genuine sense of reflection there; a real space to grieve not just the loss of another human life, but the momentary loss of your place in the world. A feeling that was quite visceral for many of us at the same time.

Despite the planetary clusterfuck it was mostly written in, Joy’All is Lewis’ brightest, grooviest and coolest album yet. The 10 tracks live up to the title they’re packaged under. Even “Balcony,” which she wrote as a tribute to a friend who died by suicide during lockdown, evokes a celebratory memorial rather than a solemn eulogy. When talking with Paste seven years ago, Lewis mentioned that she has full shoeboxes of lyrics. To no surprise, her prolific tendencies continue today—and she’s pretty adamant about not losing inspiration. “I don’t experience writer’s block, nor do I experience imposter syndrome. People are like, ‘I feel like an imposter.’ It’s like, ‘Well, maybe you are!’” she adds. When the world shut down three years ago, Lewis was working with Chicago poet and rapper Serengeti and Minneapolis multi-instrumentalist Andrew Broder, sending songs back and forth in, what she calls, their own “little version of the Postal Service.” Around that time, “Psychos” and “Giddy Up” were already finished, but the bones of Joy’All had not come alive just yet.

It was during lockdown, when Lewis took part in a songwriting challenge hosted by her friend and collaborator Beck, that she wrote nearly half of Joy’All (“Puppy and a Truck,” “Love Feel,” “Chain of Tears” and “Balcony”). “That was such a great thing to be a part of, just in learning more ways to do your craft. I write and it’s almost mystical. I don’t really know how it happens,” she says, before pausing briefly. “Well, I know how it happens with every song, but it comes through in a way that feels like I’m not in complete control of it.” Beck’s program wound up being a real grounding and energizing moment for Lewis, as she was tasked with fully zeroing in on what type of song she could build with specific limitations or guidelines in place.

“I usually start with a piece of a poem or short story and then find the instrument that makes the music to accompany it. And that could be a bass, vibraphone or drum. Whatever is in the room, I’ll use it to bring the song into the world. Or I’ll freeform phonetics, where you find the chords in the music and then the vowel sounds become a story. And then you plug in whatever you’re musing on at that time. The songwriting camp was amazing, because it was very distinct direction: ‘Write a song with 1-4-5 as the chord changes,’ which, apparently, is every pop song ever written; ‘Write a song with all clichés.’ That’s ‘Love Feel,’ where I looked up all of the tropes in Top-40 country songs. Any new way to do the thing, I’m open to learning about,” Lewis adds.

Credit: Bobbi Rich

She compares the songwriting camp to Fight Club when I press about who else was in her cohort, which I’m more than certain was a star-studded cast. “The first rule of Fight Club is that you don’t talk about Fight Club, so I’ve already blown that,” she jabs back. “I’m going to refrain from mentioning the people in the group, unless they want to come forward after reading this article. Make yourselves known, people. Make yourselves known.” Nonetheless, even though Lewis saw the whole venture though, the whole ordeal was an intimidating one (and a huge commitment during a time when creative tasks performed at home felt daunting)—and a few of the participants had dropped out by the workshop’s end. “You have to have the bandwidth to write, record and then, somehow, figure out how to upload it to SoundCloud. Those are, like, three separate parts of the brain: the uploading part, the poetry part and then the engineer part,” she adds. “Some people clearly had full studios at their disposable and it was fully produced music, which was like, ‘How did you do that in 24 hours?’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-