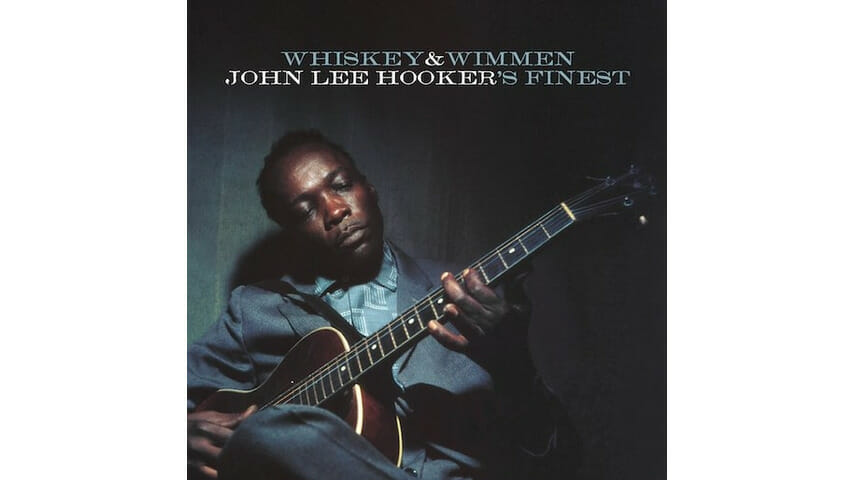

John Lee Hooker: Whiskey & Wimmen: John Lee Hooker’s Finest

It’s not actually clear when bluesman John Lee Hooker was born. He claimed

1917, but according to the Mississippi Blues Commission, census records from the area near Tutwiler, Miss. where was supposedly born, indicate he was several years older.

No matter. The truth—in regard to the blues, anyway—has always been relative. And if the man himself said 1917, then this is the year in which we’ll celebrate his centennial.

Whiskey & Wimmen: John Lee Hooker’s Finest, a new 16-track compilation from Vee-Jay, does just that. Vee-Jay was just one of many record labels that Hooker worked with over his multi-decade career, and this collection—primarily focusing on his most prolific period in the 1950s and ‘60s—includes songs originally released on three other labels, as well.

Compilation CDs of Hooker’s work have been released by the dozens since the ‘90s, and in some ways, this one is no different: it highlights the work of the bluesman who went on to influence the future of rock ‘n’ roll—The Rolling Stones, The Yardbirds, The Animals, Bonnie Raitt, Santana and George Thorogood, to name a few.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-