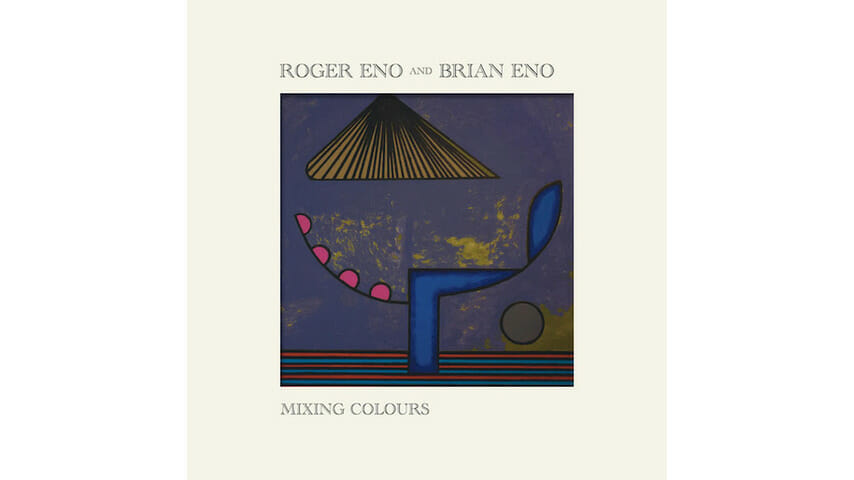

Roger and Brian Eno Try Mixing Colours But Mostly Get Gray

While elegant, the brothers are often shyly subdued

Composed over the course of 15 years, Brian Eno described his collaborative effort with his brother Roger as a conversation, with each instrument acting as “one island in the limitless ocean of all the possible sounds that you could make.” Unfortunately, those islands are often miles apart, separated by time and distance.

Each track on Mixing Colours is haunting and minimal and, at times, quite vibrant. After all, the album represents an obsessive need to illustrate with tonal color, each song doing so through names of gemstones, plants and weather phenomena that have become synonymous with the colors they represent.

The thing is, though, it’s all rather sleepy. Not that Brian’s work hasn’t verged on the sleepy before—Music for Films is as ready for quiet studying as any lo-fi hip-hop beats playlist. But when nearly every track on an-hour-and-15 minute record hinges on dour midi piano tones, it begins to verge on the forgettable. “Spring Frost” starts the album off with bright keyboard courtesy of Roger Eno, a noted pianist in his own right. It sounds hopeful and sprightly, like the melting of winter as spring hangs right around the corner. Somewhere, that thoroughfare is lost, and the “conversation” between the two amounts to little more than small talk.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-