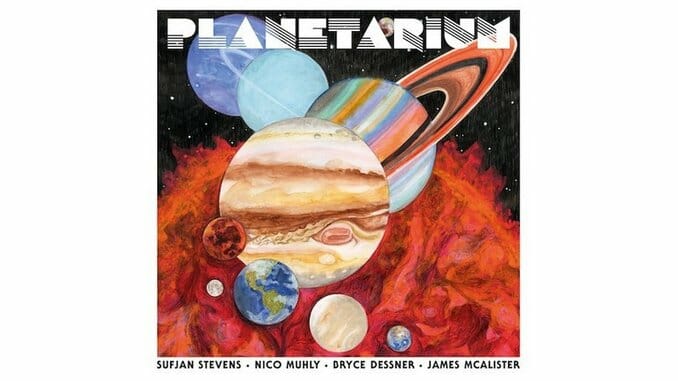

Sufjan Stevens/Nico Muhly/Bryce Dessner/James McAlister: Planetarium

Try to predict Sufjan Stevens’ next move at your own risk.

The enigmatic singer-songwriter has always seemed to do what he does musically without any apparent regard for order or expectation. He gained fame for two excellent indie-folk-pop albums themed around the states of Michigan and Illinois, and then never returned to the so-called “50 states project” he touted while promoting them. Plus, he wedged a collection of overtly Christian songs in between them.

After Illinois, he largely disappeared for five years, occasionally poking his head up with a new batch of Christmas songs or a mixed-media tribute to a New York City expressway. He returned from this relatively quiet period with an album called The Age of Adz, which found Stevens exploring electronic sounds and art rock — a far cry from the works that made his name.

Which is fine! Ol’ Suf should absolutely make the music he wants to make. His scattershot catalog reflects a musical mind that’s curious and ambitious and brilliant, and it only seems unconventional compared to the much narrower lanes of most modern musicians.

So it’s no big surprise that Stevens is following up his last album—2015’s devastating meditation on the death of his mother, Carrie & Lowell—with an electro-symphonic song cycle about the Solar System, crafted with collaborators Bryce Dessner of The National, beatmaker James McAlister and contemporary classical composer Nico Muhly.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-