How to Solve a Riddle Like The Shaggs

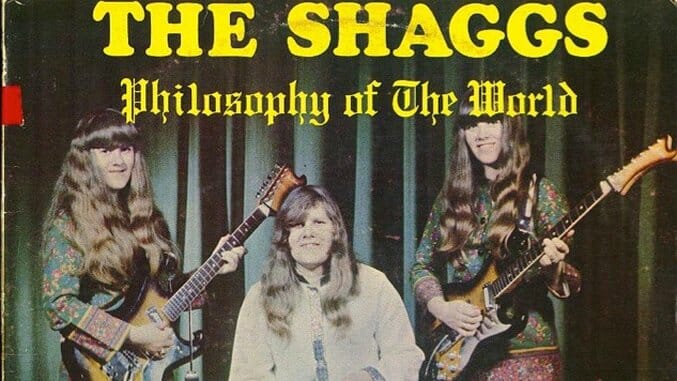

In early August, indie label Light in the Attic announced that the improbable story of the Shaggs would have yet another chapter. Forty-seven years after its release, their Philosophy of the World—perhaps the definitive outsider music artifact of the last 50 years—would be remastered and reissued as a deluxe set on vinyl, and the trio of New Hampshire sisters would be celebrated with a proper tribute show at Le Poisson Rouge in New York City. Following her triumphant return as a solo artist in 2013, Shaggs songwriter, vocalist and lead guitarist Dorothy “Dot” Wiggin would be there. Members of the Dresden Dolls, the Monks, and the B-52’s would perform, and Wiggin’s backing band would provide the music. But if you know anything about the Shaggs’ story, you’d know that nothing ever happens quite as planned. This next chapter would be no different.

Dot, herself, was the first to drop out, citing health issues. One by one, most of the identifiable names followed until what was left was a ragtag group of exceptionally skilled but little-known underground musicians (hardcore punk band Bi-Tyrant, experimental guitarist Ava Mendoza, avant-jazz performer Jessica Pavone, etc.). What they lacked in name recognition they more than made up for with a deep admiration for the music of the band they were there to celebrate, and they gamely took turns doing their best to recreate this exceptionally nuanced, counterintuitive music. Packed with an audience comprised of New York City’s best underground free jazz and avant-garde composers, the show was a rousing success. The lack of star power was more than fitting; the Shaggs were never the kids at the cool table or even the kids at the artsy table. (In fact, they were homeschooled.) They always fit best, if they fit all, with the misfits.

That’s been the case since NRBQ’s Terry Adams discovered a rare copy of Philosophy of the World in a New York City record bin and was so taken by the music’s entrancing combination of sour guitars, heartfelt lyrics and misfiring drums that he convinced his label, Rounder Records, to rerelease it in 1980. People had known of the Shaggs before Adams rediscovered them—Frank Zappa famously hailed them as “better than the Beatles” as early as the 1970s—but it was Adams’ support that pushed the Wiggin sisters (Dot on lead guitar, Betty on rhythm guitar, Helen on drums) into the public consciousness. Ever since, they’ve represented an outpost of sorts, the last stop on the pop continuum before you drop off into freeform noise and unstructured experimentation. In the process, they have become a rite of passage for every self-identifying musical outsider. Kurt Cobain named Philosophy of the World his fifth favorite album of all-time. They were namedropped in an episode of Gilmore Girls. Neutral Milk Hotel’s Jeff Mangum is so obsessed with them that he took the Dot Wiggin Band out on tour as his band’s opening act on their sold-out reunion tour. Nearly 50 years later, there is still nothing even remotely like the Shaggs.

If she’s aware of the significance of all of this, Dot seems appreciative but unimpressed. When she released Ready! Get! Go!—her 2013 solo debut with the Dot Wiggin Band—she hadn’t played more than a few one-off shows since the Shaggs disbanded in 1975. Since the end of that tour, she has spent her time much as she had before her return to music, caring for her family and two ailing pugs back in her hometown of Fremont, New Hampshire. Ask her about the reissue and the current groundswell of attention, and she has no answers. “I had nothing to do it with—put it that way,” she says. “I was kind of surprised to hear about it. But it was a good surprise.”

Now as before, to listen to the Shaggs is to drop into an alternate universe of ‘60s pop, one where kids sing about how great their parents are and how much they love Jesus with eerie sing-along choruses and half-tuned guitars. It’s like discovering the folk music of a culture you can barely believe exists, where all of the conventions of rhythm and tone are upended. The patterns are elliptical and random. The melodies bend and sigh, often tapering off at odd points and never resolving quite where you expect. Adding to the surreal quality, it sounds as if the sisters all can play in time but can’t play in time with each other, leading to the impression of three musicians performing slightly different songs simultaneously.

Betty strums her guitar and doubles Dot’s vocals, often a beat behind on both. Helen is a wrecking ball of a drummer, going off into drum rolls whenever she feels like it, often playing loud in the song’s quiet parts and quiet in the loud parts. She clearly has some genuine chops, but one gets the impression that much of her problem was simply in syncing up with the peculiar rhythms in Dot’s songs, arrangements that were so nuanced and idiosyncratic that Glenn Kotche would have struggled to map them out. As a test, just try to ignore the drums and tap out a consistent rhythm with your finger. You will struggle.

The lyrics—the most conventional aspect in the mix—are also at times baffling in their own way. Songs routinely break meter and rhyme scheme. “My Pal Foot Foot”—a song about a lost cat—never identifies the missing character as an animal at all. The song’s protagonist goes to the cat’s house, only to be told by the people there “Foot Foot don’t live here no more.” Foot Foot eventually comes home, but by the end of the story you have more questions than answers. (Why does Foot Foot have his own house? Does he have renters?)

For years, much of the attention the band has received has had a slightly unpleasant (or at least patronizing) undertone, somewhat akin to the popular kid in high school buddying up with an awkward outcast because he enjoys prodding him to make a spectacle of himself for everyone’s amusement. Especially in the early days of their rediscovery, the music press could be downright nasty. They’ve been called the “worst band ever” more times than you can count. One infamous Rolling Stone review described them as the “lobotomized Trapp Family singers.” Even today, most of those who write about them do so from an intellectual distance, seemingly too afraid to comment much on the music for fear of not “getting” it but not digging in enough to offer any critical analysis of it, either. Instead, we get endless recitations of the band’s backstory, one that is arguably as compelling as the band’s music.

Named after the then-popular haircut, the Shaggs were not formed by three teenage girls who dreamed of escaping their small-town life and achieving pop stardom. Instead, they were formed by their father, Austin Wiggin, a strict taskmaster who dreamed of seeing his daughters on The Ed Sullivan Show. According to legend, his mother had read his palm and found that his children were destined to form a successful musical act. She’d been right about him marrying a strawberry blonde and having two sons after four daughters, so who was he to question her? So, believing it was his responsibility to make their future a reality, he pulled his daughters out of public school so that he could homeschool them and make sure that they could schedule their lives around endless hours of practicing. They would rarely, if ever, please him.

It was during those long practice sessions that Dot, Helen and Betty began to form the musical equivalent of a twin language, one that held up despite the voice and guitar lessons they were receiving concurrently. They’d been playing together for several years by the time they made the drive to Revere, Massachusetts, to record Philosophy of the World, with Austin hoping to capture the trio on tape “while they were still hot.” But the Wiggin sisters weren’t quite convinced. “I think us girls felt we weren’t ready yet,” Dot recalls. “We could have had a little more experience and practice first, but our dad thought we were ready…” she says, trailing off. “So that’s where it went.”

Opening with the title track—the first song Dot ever wrote—their aesthetic is locked in place. The guitars bleat and churn while the drums pound away a totally different pace, Dot singing in unison with her rising and falling guitar leads. She checks off a list of apparent paradoxes—the kids with short hair want long hair and vice versa, the kids with motorcycles want cars and vice versa—and no one is ever satisfied. “You can never please anybody in this world” is her gloomy conclusion, one that is difficult not to interpret as representing her frustration in never satisfying an authoritarian father.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-