U2

When U2 released All That You Can’t Leave Behind in 2002, you couldn’t help but wonder if it was a passionate return to form or merely the latest metamorphosis in the shape-shifting that marked the band’s previous decade. Understandably weighed down by its own legend after The Joshua Tree and Rattle and Hum, the group devoted the 1990s to trying to escape its image as self-serious, over-earnest rock ’n’ roll saviors.

In the process, U2 made the least-impressive music of its career, cranking out irony-loaded albums like Zooropa and Pop and embarking on tours that were more about fashion than music. All That You Can’t Leave Behind’s title was a wry commentary on the futility of trying to be something other than what you truly are (Bono spent most of his time onstage in the 1990s as Macphisto, the Fly, anything but Bono), and the music was shimmering, driving, heartfelt and full of life, as was the accompanying tour. Rather than reinvent itself once more, U2 followed with last year’s How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, an album on which the band once again engaged the world with deceptively simple songs that, after repeated spins, had the power to take listeners deeper into themselves.

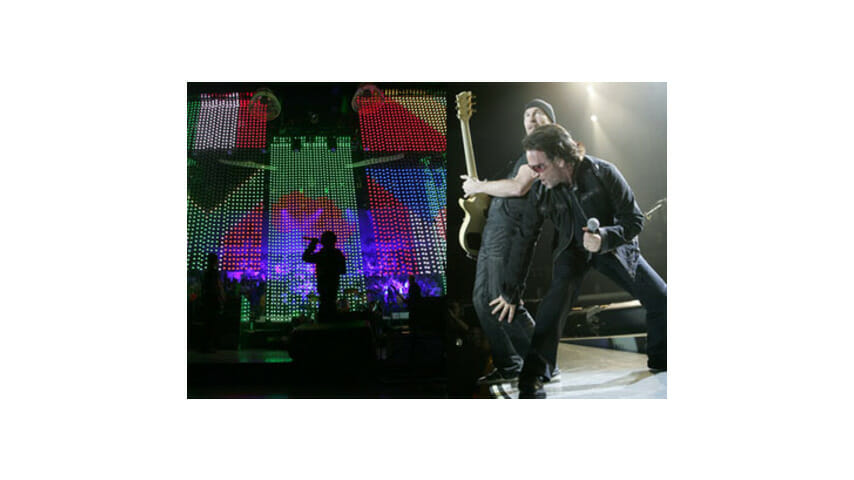

The band’s show in Chicago Saturday night—the first of four sold-out Windy City dates—was also a stunning return to form. With a set list that focused mostly on material from the new album but covered every stage of the band’s career, U2 has never looked more comfortable in its own skin. Newer tunes “City of Blinding Lights” and “Elevation” sat comfortably alongside the 25-year-old “An Cat Dubh” and “Into the Heart,” and the show-closing duo of 2004’s “Yahweh” and 1983’s “ ‘40’ “ suggests the band has come full circle.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-