On Rex Tillerson and the Disappearing Line Between Business and Politics

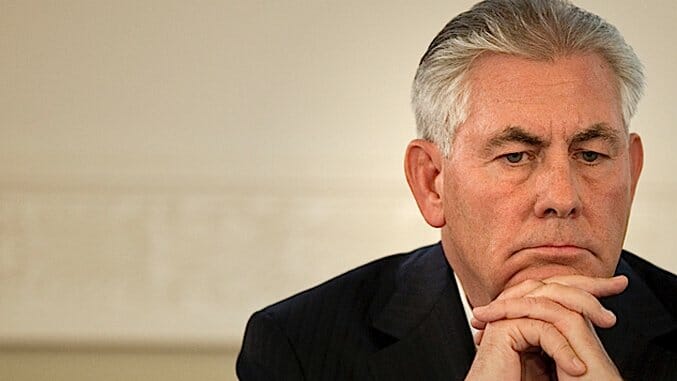

Photo by Brendan Smialowski/Getty

How does Trump do it? Every decision he makes is equal parts shocking and unsurprising. The nomination of Rex Tillerson to be Secretary of State is just the latest example. Perhaps it’s that there’s still some cognitive dissonance for most between the words “President-Elect” and “Donald J. Trump.” Would it be shocking if the President-Elect of the United States picked an oil-and-gas magnate and Putin pleaser with no government or official diplomatic experience to be Secretary of State? Absolutely. Would it be surprising if Donald Trump did this? Absolutely not.

Tillerson fits Trump’s idea of an übermensch. He’s worked at Exxon, now the sixth largest U.S. company, since 1975, consistently climbing the ranks until becoming CEO in 2006. He’s the capitalist dream personified, the sort of person a meritocracy is supposed to reward: a guy whose hard work was rewarded every step of the way by his company until he reached the top. And he did it all without his father giving him a small loan of a million dollars. No wonder Trump is impressed.

Why would a President-Elect who wears his political inexperience like a badge of honor hire an experienced diplomat to be his Secretary of State? Doesn’t it make sense his main qualifier for this position would be, you know, how to make money abroad? He’s sure got the guy for it if that’s his only concern. Tillerson generates huge profits for his company through domestic and international negotiation, he provides its goods and services throughout the world. It would seem that in Trump’s mind, there is no quantifiable difference between a business deal to generate mutual financial gains and a sweat-on-brow negotiation wherein innocent lives hang in the balance.

Speaking of innocent lives, let’s talk about Tillerson, Putin and the dark irony that his appointment shared headline space with the final farewells from some of Aleppo’s citizens. He’s been working with Putin for nearly twenty years due to Exxon’s deals with the Russian state-owned oil company, Rosneft. In 2013, he was presented Russia’s Order of Friendship, an award for work done by foreigners to better international relations and the country itself, for Exxon’s work improving Russia’s energy sector.

At the University of Texas, Tillerson gave a speech wherein he said of Putin, “I don’t agree with everything he’s doing. I don’t agree with everything a lot of leaders are doing. But he understands that I am a businessman. And I have invested a lot of money, our company has invested a lot of money, in Russia, very successfully.” As of now, it doesn’t seem like Trump would implore Tillerson to take any sort of different tact with Putin. The death of Syrian innocents at the hands of Russian-backed forces shouldn’t be reason to question the art of the deal. It’s not just Putin either, Tillerson and Trump have long track records of dealing with various autocrats for monetary gain. Money stays green even when the streets run red with blood.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-