Why Trump’s Voter Fraud Hunt Is His Own Personal Pipe Dream

Everything you wanted to know but were afraid to ask

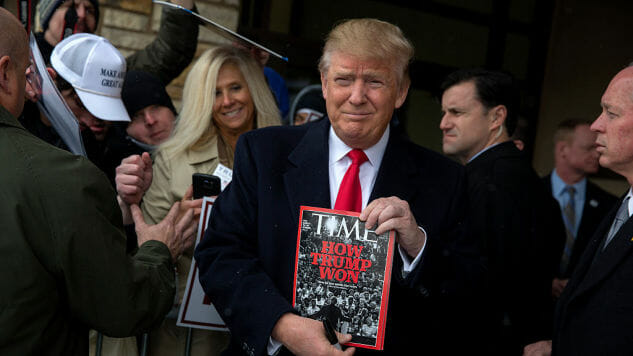

Aaron P. Bernstein / Getty

It is the gift of the dishonest to see liars everywhere, except when they glance in the mirror. Trump, the quintessential fraud, sees fraud everywhere else. He has just commanded his highly legitimate Election Integrity Commission to investigate voter data from the last election. According to an article in the Post:

The chair of President Trump’s Election Integrity Commission has penned a letter to all 50 states requesting their full voter-roll data, including the name, address, date of birth, party affiliation, last four Social Security number digits and voting history back to 2006 of potentially every voter in the state.

The reaction of the states to this dream-like proposal was not as ecstatic as one would have hoped.

States began reacting to the letter on Thursday afternoon. “I have no intention of honoring this request,” said Governor Terry McAuliffe of Virginia in a statement. “Virginia conducts fair, honest, and democratic elections, and there is no evidence of significant voter fraud in Virginia.” Connecticut’s Secretary of State, Denise Merrill, said she would “share publicly-available information with the Kobach Commission while ensuring that the privacy of voters is honored by withholding protected data.” She added, however, that Kobach “has a lengthy record of illegally disenfranchising eligible voters in Kansas” and that “given Secretary Kobach’s history we find it very difficult to have confidence in the work of this Commission.”

WE THOUGHT YOU ALREADY KNEW

The interactions of state and federal law with election records are as you might expect. Within the broader framework of national rules, there exists a patchwork of here-and-there data collection. “While the files are technically public records,” Christopher Ingraham writes, “states usually charge fees to individuals or entities who want to access them. Political campaigns and parties typically use these files to compile their massive voter lists.”

Trump is like an author, writing a story backwards: he begins at the conclusion and goes to the premise. The President is searching to find the thread of a mystery, whose solution he believes he knows. Reality doesn’t agree, as it tends not to do when Trump is involved. The states are aware of the President’s entertainments, and are not thrilled by them. Given the incredibly public and, frankly, dreary nature of our public vote-counting, it is nearly impossible to steal an election. Even your step-uncle raving about sharia and the raised prices for lawnmowers understands this, at some amphibian-brain level.

To call for this vast swathe of electoral data is not just impractical and an overstatement of the White House’s power; it’s classic Trump. Broad, dumb strokes masquerading as brassy self-confidence. There’s no need to ask for the entire country’s data set, when a few key states would do. Why would Trump bother with Alaska or Montana, for instance? If his intent was genuinely to drive down Hillary’s vote total, he’d aim for Pennsylvania or Florida. But of course, this is not how Trump thinks.

The real, too-legit-to-quit story is not voter fraud. Voter fraud on a large scale does not exist in the United States. What is worth discussing is how Trump’s imagination works, and what that shows about national policy.

EVERYDAY WE WRITE THE BOOK

Trump has imagined himself to be many things that weren’t the case: a successful businessman, in good health, a popularly-elected President of all the people. None of which existed. The hunt for voter fraud is one of these illusions. In this case, I don’t believe Trump is lying. The President is deluding himself, to use the polite term. He is hunting for something, anything, to support his emotional need. Trump craves the popular mandate. Because he is powerful, his needs are catered to. Because he is not a reflective man, but an old playboy who lives for self-aggrandizement and big burned steaks, he will seek whatever data conforms to the picture in his mind. This is the problem of confirmation bias. Trump gives his faith to information which affirms what he believes, and turns his back on data which refutes it. David McRaney writes about this phenomenon:

Check any Amazon.com wish list, and you will find people rarely seek books which challenge their notions of how things are or should be. During the 2008 U.S. presidential election, Valdis Krebs at orgnet.com analyzed purchasing trends on Amazon. People who already supported Obama were the same people buying books which painted him in a positive light. People who already disliked Obama were the ones buying books painting him in a negative light.

They weren’t purchasing these volumes for the data. They already knew what they wanted to hear. Francis Bacon, famous thought-haver, wrote that it was the “peculiar and perpetual error of the human intellect” to always chase after affirmatives than negatives, “whereas it ought properly to hold itself indifferently disposed towards both alike.”

McRaney continues:

Just like with pundits, people weren’t buying books for the information, they were buying them for the confirmation. Krebs has researched purchasing trends on Amazon and the clustering habits of people on social networks for years, and his research shows what psychological research into confirmation bias predicts: you want to be right about how you see the world, so you seek out information which confirms your beliefs and avoid contradictory evidence and opinions. Half-a-century of research has placed confirmation bias among the most dependable of mental stumbling blocks.

Most of us have habits to counteract this tendency. By the time we have reached the beacon of maturity—the age of Presidenting, in other words—most of us have a sense of how magical mysteries of probability work. We know that human brains are biologically rigged to love chocolate and cocaine and self-deception. We come to understand that RoboCop was not a frolicsome tale of hard Detroit justice, but a warning that the stories we tell ourselves must be questioned.

Hopefully, we surround ourselves with friends who can speak the truth to us. We pay attention to science. We get our news from multiple sources. We construct budgets, diaries, personal reviews, feedback loops. If we sat atop a huge, powerful government structure, we would perhaps consider the opinions of the other side or even hunt up facts. Trump does none of this. In his own way, he is the black mirror to Nate Silver, who was so caught up in his belief that Trump could not win that he beat a path around the data that refuted his basic assumption: Trump’s victory is impossible. Confirmation bias is like sales tax: always present but unnoticed until you come up short.

DON’T THINK TWICE, IT’S ALRIGHT

Individual men can suffer from confirmation bias this way. So can institutions. Sometimes, when we’re building our systems, we worship the Official Stories and forget the Real Facts. Season Four of The Wire is all about arranging your system so that you can get the scores you want. Pryzbylewski, former cop, discovers how teaching to the test works:

PRYZBYLEWSKI: I don’t get it. All this so we score higher on the state tests? If we’re teaching the kids the test questions, what is it assessing in them?

SAMPSON: Nothing. It assesses us. The test scores go up, they can say the schools are improving. The scores stay down, they can’t.

PRYZBYLEWSKI: Juking the stats. … You juke the stats, and majors become colonels. I’ve been here before.

There are several reasons organizations do this. Not all of them are sinister. Nancy Choi ists a few:

– We’ve already committed to the story we want to tell, and we just need to find numbers to justify the budget

– We need to instill confidence in our business to the public/investors/shareholders

– People’s bonuses depends on it and I can’t afford to lose more people

– It’s fight or flight, and I’m not going to let me and my team get fired over this

– We know it’s true in our gut. We just need numbers to show our gut’s right

Individuals and organizations have a story they tell themselves, and hew down the world to a proper shape to fit the story. The data scientist Cathy O’Neil wrote a book Weapons of Math Destruction, about the dangers of telling stories with numbers. In an interview with NPR, O’Neill explained the problem of hiring algorithms: all too often, they are fitted to what’s already been done.

[Imagine] an engineering firm that decided to build a new hiring process for engineers and they say, OK, it’s based on historical data that we have on what engineers we’ve hired in the past and how they’ve done and whether they’ve been successful, then you might imagine that the algorithm would exclude women, for example. And the algorithm might do the right thing by excluding women if it’s only told just to do what we have done historically. The problem is that when people trust things blindly and when they just apply them blindly, they don’t think about cause and effect.

This is how narratives work. Who were the two biggest names in Tech? Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. Both Gates and Jobs dropped out of college. God knows how many earnest professors have advised their bright students to quit school based on that pair alone. But we are selecting for success when we believe in this narrative. You know what the average weekly income for those only holding a high school diploma or equivalent? About $679 a week.

To suggest otherwise is to look from the big end of the telescope to fit everything to Jobs, just as Donald Trump tries to mold the nation into the shape most convenient for him. He has enough facts to convince him, but never enough to make him change his mind. Inside the White House, confirmation bias reigns, and wrings situations of inconvenient facts. They smashed the moving picture, and put a still image in its place.