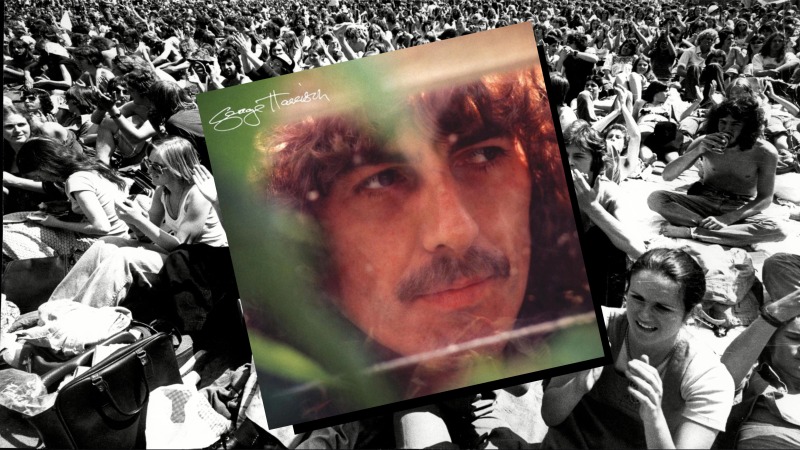

Time Capsule: George Harrison, George Harrison

The quiet one’s oft-overlooked eighth album stands as one of his most complete and cohesive works, shaped by a rare moment of inner and outer peace.

I’m certainly not the first one to pit the Beatles’ solo careers against each other, and I know I won’t be the last. When people debate the best solo Beatles album, the conversation almost always circles around Ram, Plastic Ono Band, Band On the Run, Imagine, and, of course, All Things Must Pass. Ringo can get an honorable mention if we’re being generous. But George Harrison’s sneaky little eponymous record from 1979 deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as his previous works but rarely is.

Ever the “quiet one,” Harrison distanced himself from the music industry in the wake of his 1974 American tour, which saw him running on fumes (alcohol and cocaine) to get through the gigs (he wouldn’t tour again until 1991). Then came Extra Texture (1975) and Thirty-Three & ⅓ (1976). By 1977, he’d finally given himself a true break from music, setting it aside completely for a year while he immersed himself in Formula 1 and his relationship with Olivia Arias. Olivia, a marketer for A&M Records, had been instrumental in helping him recover from that grueling mid-’70s stretch (they’d marry and have their son, Dhani, in 1978).

More or less, 1977 was Harrison’s gap year—probably the gap year he should’ve taken immediately after the Beatles ended, but didn’t have time for because they were all suing each other into oblivion. Most of that year was spent in Maui with Olivia, far from the industry grind, though his friends at the racetrack kept teasing him about when he’d finally write a song about Formula 1. In an interview promoting the album, Harrison told Rolling Stone: “I was getting embarrassed because I was going to all these motor races, and everybody was talking to me like George, the ex-Beatle, the musician, asking me if I was making a record and whether I was going to write some songs about racing, and yet musical thoughts were just a million miles away from my mind.”

He eventually wrote “Faster,” later dedicated to Ronnie Peterson who died in a crash at the 1978 Italian Grand Prix. The song, with its racecar engine revs and tales of a master of speed, kicked Harrison’s songwriting gates back open. A song dedicated to a childhood passion speaks to the inherent peace and happiness he’d found by 1978; you can hear the weight leaving his shoulders as he sweeps over the chorus (“He’s a master of going faster!”). The rest of the songs that followed were inspired by that love and happiness and peace he’d found; in Olivia, in Dhani, in himself, in his non-musical identity. The album radiates a lightness that Harrison hadn’t captured on an album in years.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-