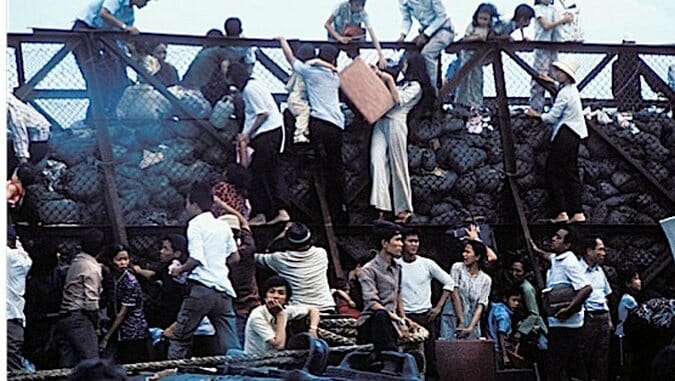

Last Days in Vietnam

Beyond slavery (and Cvil Rights), the mistreatment of Native Americans and a woman’s right to vote, the Vietnam War might be the most ignominious stain on American history. Sure, the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, same-sex equality and wealth disparity might make that list, too, in time, but Vietnam—a.k.a. the living-room war—fervently consumed the American conscience for over a decade. It was something new, too. The two Great Wars had us justly battling tyranny, championing the oppressed and righting wrongs on the road to freedom. Korea was something else, something more complex, something that appeared to be in the same arena of righteous and yet, it was really a Cold War bellwether delineating the fractious ideological divide between democracy and communism. Tough lessons were learned from that war, but Vietnam, in an era of burgeoning liberalism, free love and racial integration in the wake of Ozzie and Harriet idealism—and further inflamed by the mandatory enlistment for the draft—touched off a cascade of social unrest and activism that caused the United States to reconsider its foreign policy, something that has rippled forward to the wars that confront the U.S. currently.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-