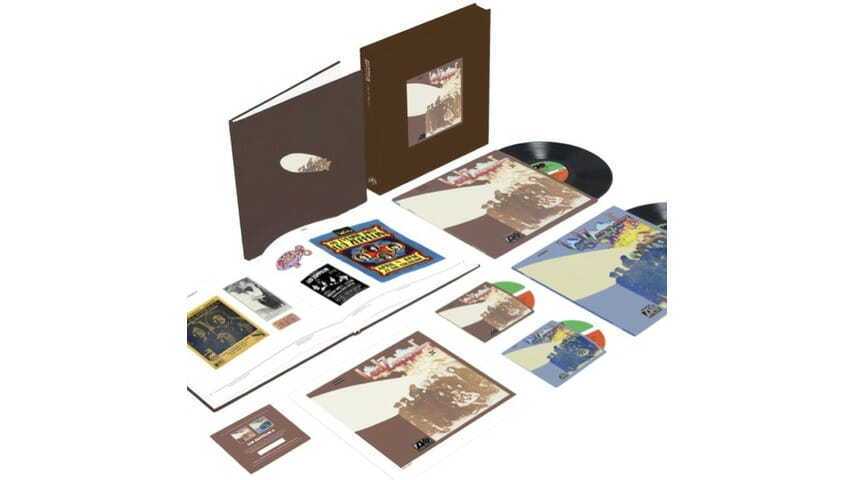

Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin, II, III Reissues

Individual Ratings:

Led Zeppelin: Remastered Album (9.5), Deluxe (5.0)

Led Zeppelin II: Remastered Album (9.5), Deluxe (8.0)

Led Zeppelin III: Remastered Album (9.0), Deluxe (9.0)

Led Zeppelin reinvented the vocabulary of rock music many times throughout their decade-long career, but their most radical burst of creativity came straight out of the gate. In a historic run shorter than two calendar years, the quartet released three mind-altering rock milestones—twisting blues riffs (and rips), metallic noise, incense-tinted folk, Indian drones and flower-power psychedelia into a magnetic yet indefinable sound often generically labeled “hard rock.”

Such a shame, then, that these albums—on CD form, at least—sound like they were recorded in a tin can. For years, Zep-heads have tolerated the murky fidelity of the ‘90s remasters, but thanks to a new expanded reissue campaign led by guitarist-producer Jimmy Page (which will eventually trace the band’s entire studio output), Led Zeppelin I, II and III finally punch and shimmer instead of fizzling in fuzz.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-