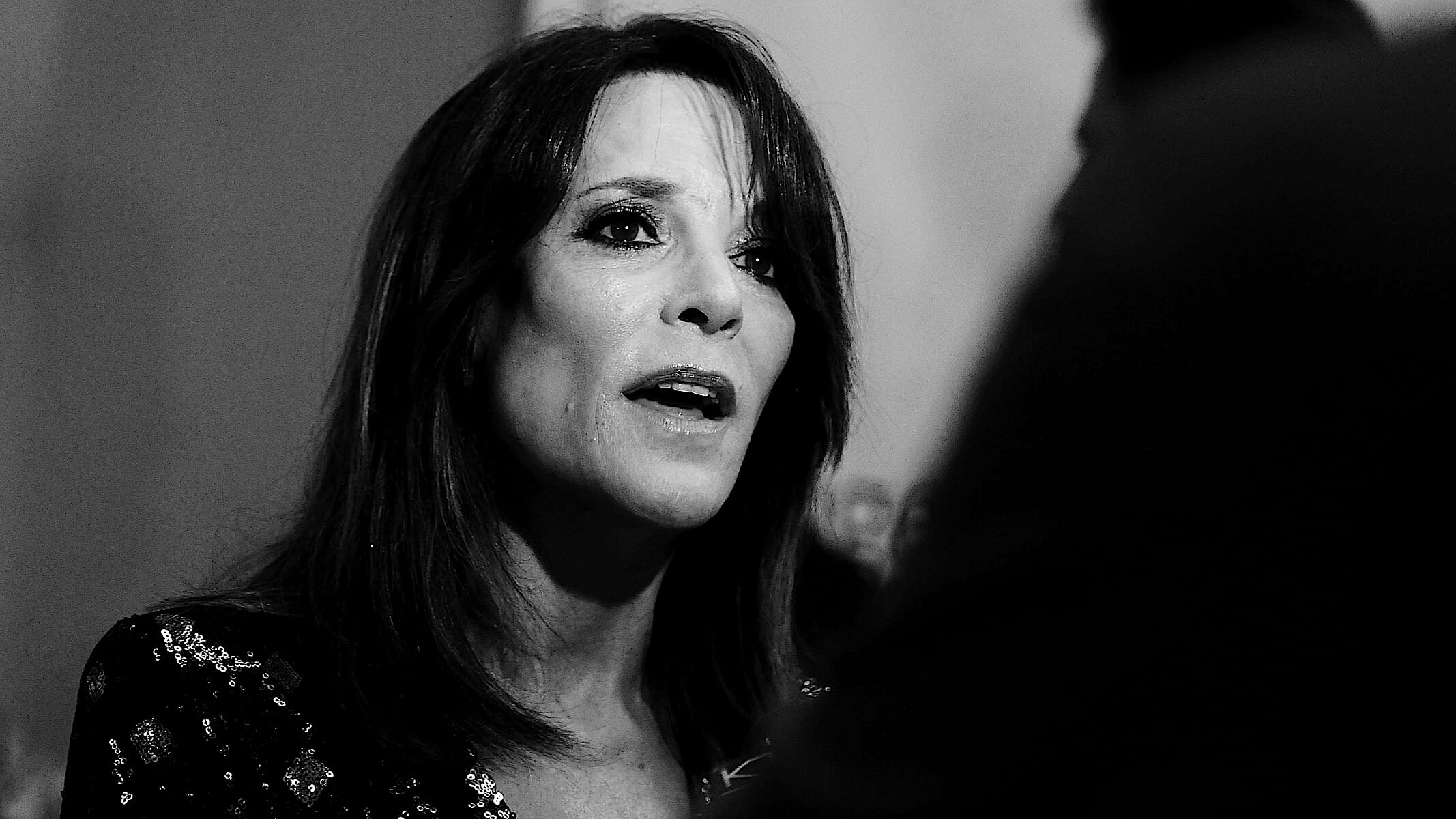

Marianne Williamson Knows Why You’re Depressed

Photo by Araya Diaz/Getty

In A Politics of Love, Marianne Williamson makes the case for a new spiritual politics. The thesis of her book, and her campaign as well, can be summed up as follows: “in order to survive and thrive in the twenty-first century, we must make our love for one another the central factor in all political decision-making.” It’s about as simple as that, but it’s also precisely that complex. Marianne Williamson wants us to consider why an ideal so elegant in the abstract remains so impossible in practice.

Williamson’s most provocative line of argument, and the one that predominates over her theory of politics more generally, takes aim at our modernist preoccupation with cold, hard facts. She explains that at least since the 1980s, American politicians have become excessively rationalistic, more focused on quantitative measures and tangible facts than the “tender mercies” of compassion and spirituality.

Williamson describes this lack of emotional intelligence as a problem spanning decades, and it culminates in the electoral disaster of 2016. The most salient distinction between Bernie and Hillary, for Williamson, wasn’t really about policy differences. Rather, it was the same factor that accounts for the rise of Donald Trump: the ability to politicize emotion. “It’s not that either [Bernie or Trump] necessarily had better plans for dealing with all that suffering than did Hillary Clinton,” Williamson says. “It’s just that they’re the only two candidates who acknowledged all that suffering. And that made all the difference.”

Williamson concludes that “we need to break free of the rationalism constraining our politics over the last few decades; such rationalism is too narrow to adequately describe our real problems or to adequately address them.”

Williamson’s critique of rationalism might sound strange, or even alarming, at a time when the notion of post-truth politics has become such a powder keg. A confluence of factors—including epistemic fragmentation via social media, conspiratorial fantasies, and the vertiginous paradox of fake news—forms what feels like a growing crisis in social reality. In many ways, this crisis constitutes the central problem of mass politics today.

Some have drawn comparisons between Marianne Williamson and Donald Trump, usually in an attempt to discredit her. But such dismissal is mistaken. In truth, the left should be so lucky.

One reading of Williamson’s significance is that she’s offering, perhaps for the first time in our political system, a left politics that is aesthetically and epistemologically postmodern, and yet morally intelligent and spiritually sensitive at the same time. In this sense, Williamson’s politics of love can be understood as another step forward in the very long, very complex contest between materialism and idealism, Marx and Hegel, base and superstructure, political economy and cultural theory. The essence of that debate turns on whether tangible conditions or immaterial ideas move the world. In that sense, when viewed in the context of left intellectual history, Williamson’s theory of politics has much in common with the Western Marxists of the Frankfurt School.

Like Williamson, the Frankfurt school philosophers were concerned with the excesses of cold rationalism as they related to the degeneracies of advanced capitalism. Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno wrote Dialectic of Enlightenment in the shadow of Nazism and World War II, at a time when the world seemed to have failed itself. As the text famously begins, “Enlightenment, understood in the widest sense as the advance of thought, has always aimed at liberating human beings from fear and installing them as masters. Yet the wholly enlightened earth is radiant with triumphant calamity.”

Like Horkheimer and Adorno did in the 1940s, Williamson wants to draw our attention to the corrosive effects of excessive rationalism today, exposing its false prestige and fundamental incapacity to guide us.

But quite unlike those depressive bookworms of the Institute for Social Research, Williamson’s political prescriptions are hopeful, actionable, and glowing with warmth.

![]()

Williamson’s moral epistemology has, more than once, put her in an awkward conversation with science. As soon as she entered the national political consciousness, she’d already been pigeonholed as a bourgeois new-age kook, a glamorous but batty lady who peddled crystals and spurious herbal remedies.

But misleading stereotypes aside, Williamson has been most aggressively called to account for her comments on vaccines and antidepressants. Though she never quite opposed either of those things, Williamson has, at times, expressed skepticism, and it’s the type of skepticism that sets off shrieking alarm bells in most liberal circles.

Most notoriously, in June she called mandatory vaccinations “draconian” and suggested that she takes an essentially “pro-choice” position on them. Within a day, she retracted the comments and apologized, stating that she does not question the safety or efficacy of life-saving vaccines. When asked about it since, she’s clarified that she supports mandatory vaccinations.

Williamson now uses the issue as an opportunity to pivot to her broader critique of the for-profit pharmaceutical industry. The more important point, for Williamson, involves the unacceptable way medical care operates in neoliberal capitalism. All in all, Williamson’s misstep on vaccines should be viewed in the context of her concerns about unregulated market forces, not medical science per se. Her platform on healthcare states the need for “cutting-edge public health science instead of following the lead of lobbyists for industries whose sole focus is profit.” And there, she unquestionably has a point.

![]()

When it comes to her comments on antidepressants, the picture is more complex. At various times, Williamson has questioned the efficacy and safety of antidepressants. For instance, she tweeted in 2014: “Sadness is not a disease. We don’t need pharmaceuticals to get through a dark night of the soul.” Her most problematic comment came on a podcast with Russel Brand, when she referred to clinical depression as a “scam.”

When Anderson Cooper grilled her ferociously about it, she acknowledged that she shouldn’t have said “scam.” But beyond that, she more or less dug her heels in.

Drawing on 35 years of experience in carework and counseling, Williamson argued that the biggest reason so many people are depressed today is because contemporary life is so dissatisfying and dehumanizing; neither the root cause, nor the most effective solution, to that problem is chemical in nature.

Cooper dismissed Williamson’s argument as irresponsibly retrograde. He said, reciting the standard dictum, that “clinically depressed people are not depressed just because the world is depressing; they have a chemical imbalance.” Anderson Cooper and others who’ve slammed Williamson on this are under the impression that there is one way, and only one way, to understand clinical depression: that it results from a spontaneous chemical imbalance in the brain.

But this badly misrepresents what doctors and socials scientists know, and don’t know, about depression.

![]()

In a new book, journalist Johann Hari examines the complex features of contemporary depression and investigates its poorly understood causes. As one of the most comprehensive and detailed accounts of depression in recent years, Hari’s work has been praised by a broad coalition of progressive figures, including Naomi Klein, Glenn Greenwald, George Monbiot, Bill Maher, Arianna Huffington—and even Hillary Clinton offered a blurb.

After years of research and hundreds of interviews with doctors, social scientists, and people suffering or recovering from depression, Hari arrived at an inescapable conclusion. The dominant model of depression proffered today—the chemical-imbalance model that defines clinical depression as a physical dysfunction of the brain—is simply not tenable.

Hari writes: “We have been systematically misinformed about what depression and anxiety are . . . The primary cause of all this rising depression and anxiety is not in our heads. It is, I discovered, largely in the world, and the way we are living in it.” Hari’s book uncovers decades of research confirming the social and environmental causes of depression, and deconstructs the myth that depression is solely the result of a spontaneous chemical imbalance.

Prior to his research, Hari had undergone thirteen years of pharmaceutical treatment for his clinical depression. He never wanted to refute the chemical-imbalance model. In fact, he’d always been deeply attached to it, because of the stable narrative it gave to his sadness. “Once you settle into a story about your pain, you are extremely reluctant to challenge it,” Hari writes.

But after all that time on antidepressants, Hari noticed that his depression hadn’t gone anywhere. In the end, he had nothing to show for it but weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and an escalating dosage. When he began to investigate why, he was shocked to find out that his experience was typical: Anywhere from 65 to 80 percent of people on antidepressants are still depressed.

One of the doctors Hari spoke to was Dr. Irving Kirsch, a leading researcher at Harvard and an expert on the effects of placebos. Originally a big fan of prescribing antidepressants, Kirsch made a shocking discovery: only 25 percent of the effects of antidepressants are explicable by chemical intervention; placebo effects and natural recovery account for the remaining 75 percent in measured effectiveness.

Through FOIA requests with the FDA, Kirsch also uncovered how pharmaceutical companies selectively publish trial results. Viewed in context, the supporting research becomes almost completely spurious. In one trial, for instance, 245 patients were given Prozac, and yet the company published results for only 27 of them. That means almost 90% of the trial’s results were swept under the rug.

Where pharmaceutical companies haven’t been able to marshal favorable research, they’ve simply lied about it. When GlaxoSmithKline couldn’t wrangle up any research to justify selling one of its antidepressants to teenagers, they marketed the drug to teenagers anyway. A cold internal memo determined: “It would be commercially unacceptable to include a statement that efficacy has not been demonstrated.”

Hari speaks with a string of other psychiatrists, professors, and researchers who refer to the chemical-imbalance model as follows: “deeply misleading and unscientific”; “just marketing copy”; “a myth”; “a lie”; or most simply, “bullshit.” Ultimately, Kirsch concluded that the chemical-imbalance model was originally a simple misunderstanding by scientists. But now, “it has come as close to being proved wrong, he told [Hari], as you ever get in science.”

Of course, not all scientists and doctors agree. But the picture Hari assembles is a far cry from the reductive treatment that people are throwing in Marianne Williamson’s face. Hari’s research indicates that the chemical-imbalance model is less a scientific paradigm, and more a marketing narrative, one carefully crafted by for-profit pharmaceutical companies and waived in by complicit regulators.

![]()

Of course, anyone can poke holes in mainstream theory. But how about an alternative? If not a chemical imbalance, then what causes depression, and how do we treat it?

Hari’s insight begins with the DSM’s so-called “grief exception,” which until 2013 allowed psychiatrists to withhold a diagnosis of mental illness for patients who’d recently experienced the death of a loved one. The grief exception was originally adopted because the symptoms of grief so closely mirrored those of clinical depression. Noting this, Hari hypothesized that depression was a more generalized form of grief. Rather than despair over a death, depression is the profound and ineffable mourning we experience over our disconnection from the things that matter in life.

Hari identifies seven vectors of disconnection that have been shown to contribute to depression: the denial of fulfilling work and lack of control over one’s labor; alienation from other people; a deterioration in shared value systems; unreconciled childhood trauma; shame and a loss of social dignity; estrangement from the natural environment; and a decaying sense of optimism about the future. Confronting depression at its root requires healing those ruptures and restoring our connection with those things that have always, until things went wrong, made human life worth living.

Crucially, Hari integrates these key disconnections with the role of genes and brain chemistry. It’d be foolish, Hari argues, to dismiss physiological factors entirely. Adding eighth and ninth causes, Hari explains how neuroplasticity and genetic predispositions can increase one’s risk for severe depression. He notes as well that more severe mental conditions, such as bipolar disorder and manic depression, probably do have a more pronounced biological explanation. But these physiological criteria still require environmental triggers, and it remains gravely misleading to characterize them as the sole ontological cause of depression.

Hari’s big point is the same one made by Marianne Williamson: amid an epidemic of depression, suicide, and drug abuse, we cannot afford to ignore the social causes of depression any longer. The strict neurochemical model has done plenty to line the pockets of pharmaceutical company executives and shareholders, but it simply hasn’t done enough to make us feel any better.

![]()

The month of Trump’s inauguration, I argued that depression is a political issue. I called for a healthy skepticism over the chemical-imbalance model, as well as the one-size-fits all psychopharmacological approach to depression. In its place, I stressed our need to confront the immiserating effects of neoliberalism.

At the time, Hari’s book had yet to be published, and I wasn’t even aware of how poor the science was. My approach was grounded more in political theory than medicine or social science. My primary influence was the late cultural theorist Mark Fisher, undoubtedly one of the left’s most influential thinkers of the past decade. The world had then recently lost Fisher to suicide, and in that moment his writings on the politics of depression were inescapably apt and poignant.

Fisher is known best for his notion of capitalist realism, which refers to our shared inability to imagine an alternative to capitalism. In hundreds of pages of essays and blog posts, Fisher mourned our canceled future, and he made it his life’s work to find a way out of the trap of collective depression.

Like both Johann Hari and Marianne Williamson, Fisher didn’t entirely reject the chemical-imbalance model of depression. At best, Fisher believed it to be reductive and misleading; at worst, it concealed depression’s most actionable causes. “It is not that these models are entirely false,” Fisher wrote. “It is that they miss — and must miss — the most likely cause of such feelings of inferiority: social power.”

For Fisher, it was no mere coincidence that neoliberalism had coincided with an epidemic of paralyzing despair. On the contrary, “collective depression is the result of the ruling-class project of resubordination.” Far from a spontaneous chemical imbalance, the epidemic of depression was better understood by Fisher as a deliberately manufactured mass affective state, imposed on us precisely for its disabling effects.

Depressed people don’t protest; depressed people don’t vote.

But what if they did? Fisher always—until the bitter end, I like to believe—did what he could to resist a drift toward nihilism and abstentionism. Instead, he preferred to underscore the solidaristic possibilities of shared sadness: “Inventing new forms of political involvement, reviving institutions that have become decadent, converting privatised disaffection into politicised anger: all of this can happen, and when it does, who knows what is possible?”

Today, Marianne Williamson is the candidate with the greatest ability to pick up where Mark Fisher left off. For all the flack she’s gotten about it, Williamson’s point is almost identical to that of Mark Fisher: We cannot meaningfully discuss sadness, despair, and mental illness without also having a critical conversation about capitalism.

The worst takes on Williamson have attempted to characterize her as an irresponsible solipsist, as though all that mattered were our siloed, internal emotional lives. That caricature can be extrapolated, squaring the distortion, into painting her as a neoliberal partisan of individual responsibility.

But these criticisms confuse a subjective politics of self—which Williamson rejects—with an intersubjective politics of love. Crucially, Williamson characterizes emotional misery as a collective problem in need of a collective solutions:

“What feels to me to be lacking now is a sense that we are going through this crisis together. Too many seem to think today that their stress and anxiety is theirs alone, or at the least not deeply related to the stress and anxiety of others . . . today, people are oddly cocooned in their misery. Many fail to realize either the collective reasons for our problems, or the collective changes necessary in order to solve them.”

A Politics of Love underscores the link between our living conditions and our emotional lives. Williamson highlights the collective pain felt by so many in this country, and explicitly ties that pain to the failures of our cold economic system.

The title of Williamson’s book is a bit of a misnomer. In addition to love, Williamson wants to harness for political purposes our righteous anger and shared sadness too. In this way, Williamson stands for a politics of affect more generally, and she believes that collectivized emotion is the most important weapon the left can arm itself with right now.

![]()

In one of the few good takes I’ve seen about Marianne Williamson, a writer at The Outline puts it quite simply: In content if not always in form, Marianne Williamson is a relatively straightforward religious thinker. Williamson’s spiritual progressivism comes as an unlikely answer to an outstanding need for quite some time: the necessity of mobilizing a religious left.

For too long, our most vital social justice movements have been estranged from American religious communities. The Democratic Party has always found itself uncomfortable, inept, or disingenuous when it comes to matters of spirit and God, and this has been to its severe electoral detriment.

But such is Williamson’s unique advantage: She has the ability to talk about God in a way that feels like it applies to everyone, believer or not, and she does so while seamlessly supporting redistributive economics, gay rights, and access to abortion. For Williamson, God is nothing but love, and left politics flow naturally from that. She makes it look easy, but pulling that off is not something our political system has ever seen before.

The challenges, implications, and pitfalls of a model of politics like Williamson’s are numerous, complex, and far-reaching. From a left or socialist perspective, it bears mentioning that, like Warren, she balks at the socialist label and hopes to resurrect a mythical form of capitalism that magically works the way we want it to. But if we were to enact half of her economic platform—which includes universal basic income, student loan forgiveness, a Green New Deal, a government-matched universal savings program, and universal healthcare—we’d be well on our way to robust social democracy. The rest is just language games.

And in any case, Marianne Williamson’s campaign isn’t really about problems of policy. It’s about deciding to take seriously a much deeper problem, and that’s the terrible impasse highlighted by Theodor Adorno in 1951: that wrong life can’t be lived rightly.

Despite all the handwringing over Williamson’s supposed mysticism, the deficiency we face today is not one of science. If only. Our deficiency is instead one of love and care as a normal part of our social and economic lives. Curing that deficiency may well take a miracle. But as she notes in A Return to Love, the book that launched her career, sometimes a miracle is a reasonable thing to ask for. And once we find it, we’ll see that what we’ve been looking for has always been there, right in front of us, all along.

Tom Syverson is a writer living in Brooklyn. Follow him on Twitter.