The Curmudgeon: The Unsung Heroes Behind Every Great Rock Song

What makes great rhythm guitarists so essential is their ability to pull together the three crucial music elements of any song: the beat, the chord changes and the tune.

Photo: Getty Images

Once upon a time, two guitar-playing brothers grew up in Dallas. Neither could sing very well, but the older one, Jimmie, specialized in vamps and riffs, while the younger one, Stevie, emphasized single-note runs. Jimmie joined a blues-rock band in Austin, and his compact chord figures powered that group like the diesel engine on a White Freightliner roaring across I-10. Stevie formed his own blues-rock group in Austin and used its as a launching pad for one rocketing solo after another. In the ‘80s, when they were both at their peaks, Stevie became a proverbial guitar hero, while Jimmie was overlooked as no more than an efficient part in a powerful machine. But if we go back and listen to their records today, Jimmie’s work with The Fabulous Thunderbirds is far more enjoyable than Stevie’s work with Double Trouble. And the reason is that Jimmie never wasted a note; he served the song. Stevie expected the song to serve him, and he wasted more notes than many guitarists will play in a lifetime.

Thirty years later, it’s a lesson that continues to bear itself out across the rock ‘n’ roll spectrum. There are a lot of things, for example, to like about Waxahatchee’s most recent album, Out in the Storm, the most obvious being Katie Crutchfield’s special ability to open a window on a woman’s experience in a troubled romantic relationship. But just as important in my book is her ability to create and hammer home rhythm-guitar riffs that grab the ear and don’t let go. She uses the post-punk template of another pioneering rhythm guitarist, Sleater-Kinney’s Corin Tucker, contrasting soaring female vocals against brittle, crunching guitar riffs. The album even features Katie Harkin, Sleater-Kinney’s touring lead guitarist since 2015, and Harkin responds to Crutchfield’s arresting chord voicings with simple, premeditated single-note parts that reinforce the main thrust of a song like “No Question” without ever distracting from it. And that’s how it should be: The lead guitar should support the rhythm guitar, not the other way around.

Why do the sensational soloists get all the glory while the chording vampers are left in the shadows? Why did fans scribble “Clapton Is God” on bathroom walls and not “Cropper Is God”? Virtuosity has never been essential to rock ‘n’ roll.

Out in the Storm opens with a pumping, anthemic figure that climbs down a melodic stairway one bar at a time to introduce “Never Been Wrong.” The guitar evaporates on the verse but comes roaring back to shadow the vocal line on the chorus. Before you even hear the lyrics, you get the sense of pent-up frustration finding a long-sought release valve. On “Silver,” the lyrics are mere footnotes to explain the story embodied in the riffs: the intro’s surging blast of lust and yearning and the verse riff that ties that longing into knots of disappointment. Even on a song with a tempo as slowed-down as “Brass Beam,” it’s the minor-key motif that captures the exhaustion of keeping a bad relationship going for too long.

Out in the Storm is one more reminder that the true instrumental heroes of rock ‘n’ roll are not the lead guitarists but the rhythm guitarists. Those solos and fills are enticing embellishments, handsome accessories to a song, but they don’t define the song the way chordal riffs do. You can change the solos, and the song doesn’t really change. But change the rhythm-guitar figures, and it’s a different song. The riffs are the cake, the solos the icing. The riffs are the house, the solos the paint and weathervane.

What makes rhythm-guitar phrases so essential is their ability to pull together the three crucial music elements of any song: the beat, the chord changes and the tune. The choppy phrasing of the pick’s downstroke across the strings shares the percussive quality of the drums. The three-or-four-note chords combine the notes of the singer, bassist, keyboardist and lead guitarist into one voicing. And the top notes of those ever-changing voicings imply a melody that complements the vocal line. The riff is the glue that holds the band together; it’s the definer of the music’s character.

Waxahatchee’s Katie Crutchfield crafts rhythm-guitar riffs that grab the ear and don’t let go. (Getty)

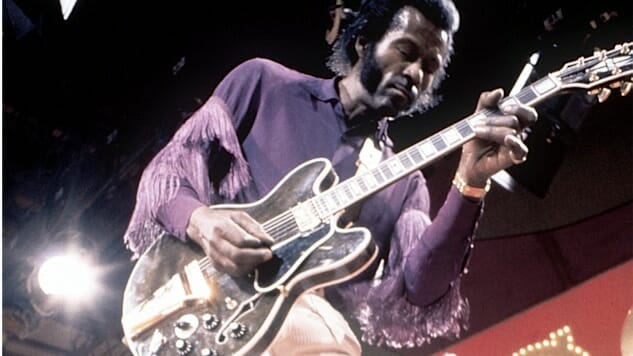

And yet, for some reason, it’s the lead guitarists we lionize. Examine any list of rock’s greatest guitarists, and you find the same names at the top: Jimi Hendrix, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Duane Allman, Jeff Beck, Jerry Garcia, Slash, Robert Fripp, Carlos Santana, James Hetfield, Eddie Van Halen, Stevie Ray Vaughan. Amid all these lead guitarists, only Chuck Berry and Keith Richards are allowed to represent the riff-making rhythm guitarists who have had a much more profound impact on the music.

It’s not that those other names aren’t brilliant musicians, or that they never played rhythm; it’s just that they didn’t define whole new genres the way rhythm guitarists such as Berry, Richards, Tucker, Carl Perkins, George Harrison, Jimmy Nolen, Roger McGuinn, Steve Cropper, Bob Weir, Catfish Collins, Robbie Robertson, Joan Jett, J.J. Cale, Johnny Ramone, Nile Rodgers, Joe Strummer, Bob Mould, Cesar Rosas, Captain Kirk Douglas and Jonny Greenwood have. New genres, after all, are born not out of solos but out of riffs. These rhythm guitarists demonstrate how varied a rock ‘n ‘roll riff can be, ranging from Berry’s two-string blues twang to Richards’s suspended-chord voicings; from Nolen’s chicken-scratch picking for James Brown to McGuinn’s jangly, open-string sound for The Byrds; from Ramone’s staccato eighth notes to Cale’s laid-back, behind-the-beat swampiness; from Mould’s noisy roar for Hüsker Dü to Douglas’s hip-hop precision for The Roots. A rhythm-guitar riff can be exciting or boring, inventive or formulaic, just like anything else, but when it’s really good, it can create a whole new style of music.

Read: Why Hüsker Dü—Not Nirvana—Were the Real Kings of Punk’s Second Wave

So why do the single-note soloists get most of the spotlight, while the chording vampers are left in the shadows? Why did fans scribble “Clapton Is God” on bathroom walls and not “Cropper Is God”? I ascribe it to “concert-hall envy,” the mistaken notion that rock ‘n’ roll can be judged by the same virtuosity measure as jazz and classical music. Every kid who ever endured parents and teachers mocking the primitive skills of rock ‘n’ rollers has longed to cite someone who can play complicated solos speedily and cleanly. When they could point to Hendrix and Garcia, they believed they had justified their music and that those lead guitarists must be the genre’s true heroes.

But virtuosity was never essential to rock ‘n’ roll; it was at best an enjoyable accessory. Rock isn’t an art music like jazz or classical; it’s a kind of commercial folk music that relies not on unusual skills but on the combined emotional impact of riffs, beat and vocal. It doesn’t matter if you can barely play—and the earliest records by The Beatles and The Clash are testament to that—if you can come up with a song and a performance that the listener immediately wants to hear again.

The rock ‘n’ roll virtuosity contest is a fool’s game. No matter how good rock’s best lead guitarists are, it will always be easy to find jazz guitarists and classical violinists who can play just as briskly and just as cleanly over far more complicated chord changes and time signatures. Those genres train for virtuosity in an organized way that the anarchic world of rock can never match. It’s a competition that rock is never going to win, so why worry about it? Rock ‘n’ roll can be every bit as exciting as jazz or classical music, of course, when the songwriting and performance capture a universal emotion so powerfully that technical skills are beside the point. When that happens, there’s usually a memorable riff connecting the vocal to the rest of the band, and that riff is usually played by the rhythm guitarist.