There Goes The Neighborhood: Dancing Through the Bullshit Beneath the Koscuiszko Bridge

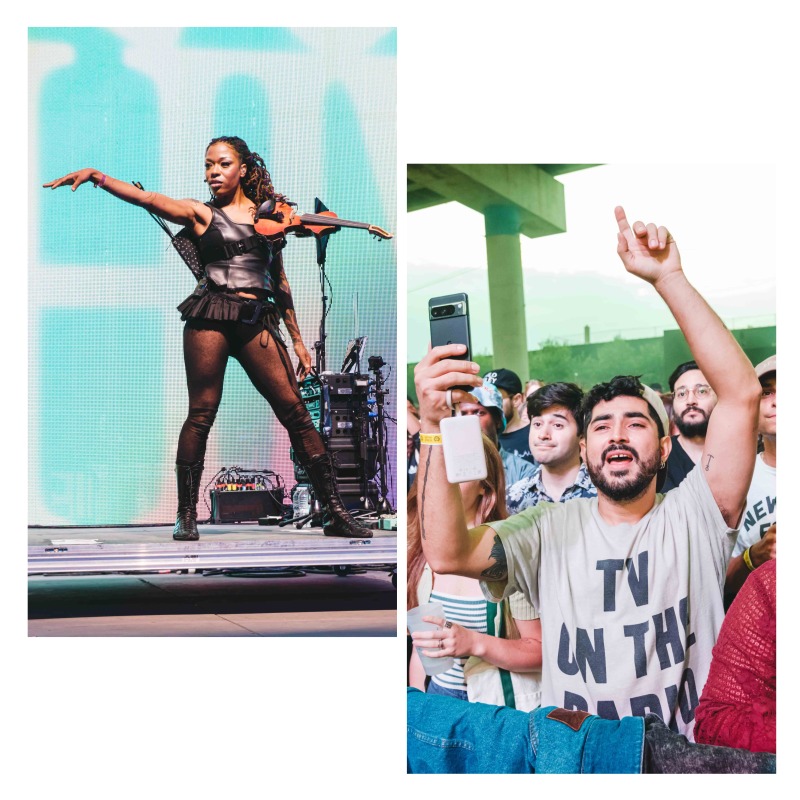

Last weekend, TV On The Radio hosted its inaugural festival in Brooklyn. With support sets from the likes of SPELLLING, Moor Mother, Sudan Archives, and Flying Lotus, the event wasn't a nostalgia dump. It was a celebration of a city at a pivotal point in its history.

Photos by Emilio Herce

TV On The Radio’s inaugural There Goes The Neighborhood festival in Brooklyn is a celebration of a city at a pivotal point in its history. With the cost of living skyrocketing and the presence of ICE and militarized NYPD forces increasing in the Trump era, things in New York can feel pretty bleak to say the least. But on the flip side, we’’ve also seen New Yorkers refuse to comply with fascist demands—New York City’s been a hotbed for organizing against the rollout of anti-trans and anti-immigrant legislation, as well as the ongoing genocide of Palestinians. Back in June, on the one day that the city’s temperature hit the triple digits, DSA-endorsed candidate Zohran Mamdani won the mayoral primary against disgraced establishment Democrat Andrew Cuomo in a historic upset, and Mamdani’s lead in the general election shows little sign of slowing. I learned after the festival that Mamdani was allegedly invited to speak at There Goes The Neighborhood but declined; appearances at events like indie rock concerts were necessary when his campaign was still getting off the ground, but at this point, the kind of people at concerts like these don’t need to be convinced to vote for Mamdani—they’re already signed up to canvas for him next weekend.

When TV On The Radio takes the stage at Under the K Bridge Park, it feels like a homecoming as soon as the opening snares and synths of “Young Liars” begin to sizzle from the stage, boiling over into the overjoyed audience obscured by an army of smoke machines. We’ve lucked out weather-wise; summer lingers just enough through the mid-September afternoon, and by the time the sky darkens, a warm breeze still sways through the crowd, which varies in age, ethnicity, gender, pretty much every conceivable category. The venue is unassuming—a park located, as the name would suggest, underneath the Koscuiszko Bridge in the industrial area where Greenpoint and Williamsburg overlap, a long but worthwhile schlep from the nearest G and L train stops. Between sets, emcee Hannibal Buress calls Williamsburg the “gentrification final boss,” mentioning that he’d seen a Capital One Bank location get priced out of the neighborhood to make way for a luxury apartment complex. You know it’s bad when even the bank can’t make rent anymore.

Throughout TV On The Radio’s set, magnetic frontman Tunde Adebimpe often introduces songs by saying the street address of the apartments where they were written and pointing in the general direction of where those were located—many just a block or two away from the park, some in buildings that no longer exist, almost all in buildings where the rent has since increased exponentially. Adebimpe mentions one apartment that he’d lived in during the early 2000s, across the street from a C-Town supermarket. Almost all of the business on that block had been replaced, “but the C-Town is still there!” he says, with a shit-eating grin. As someone who grew up in Brooklyn and has spent their entire life watching the city slough parts of itself off, it’s always funny to see what sticks around.

A year ago, TV On The Radio returned from their five-year hiatus and embarked on a 20th anniversary tour for their debut album, Desperate Youth, Bloodthirsty Babes. Following a run of dates earlier this year, the group struck while the iron was hot and announced that they’d be curating their own one-day music festival in Brooklyn. “We’re headlining, so it’d be weird if we asked, like, Doechii to do it,” TVOTR member Jaleel Bunton joked during our pre-festival Zoom call. “I think she’d be too busy.” He tells me that the band’s goal when curating the festival’s lineup was “authenticity above everything else, which automatically entails some eclecticism.” Bay Area baroque-punk band SPELLLING, experimental musician and poet Moor Mother, violin-toting dance-pop princess Sudan Archives, and EDM producer/DJ Flying Lotus all make up the festival’s support. These are artists who float between genres, never fitting neatly into any particular one, instead using their outsider status as an opportunity to carve out their own niches, often becoming uber-collaborators across genre lines.

For her most recent album Portrait of My Heart, SPELLLING frontwoman Tia Cabral recruited session musicians from hardcore bands like Turnstile and Zulu to honor her California punk roots. An Afro-Latina woman who’s spent most of her career in white- and male-dominated music scenes and a vocalist whose borderline-operatic soprano and fantastical aesthetic sensibilities are an unlikely match for the nu-metal and grunge-inflected sound she’s been drawn to, Cabral channels feelings of otherness into an otherworldly sound. Hearing her wail, “I don’t belong here!” at the chorus of Portrait’s title track during her kickoff set at There Goes The Neighborhood feels triumphant rather than mournful—she’s misfitted her way into a place where she undoubtedly belongs.

Before SPELLLING’s set begins, I have a few minutes to survey the festival grounds, check out some of the food offerings and vendors from various local businesses. Some of these are ones that Bunton mentioned by name during our conversation—a vintage clothing pop-up from local thrift store Other People’s Clothes, a makeshift roller rink and skate rental from Xanadu. “I have real philosophical and emotional conflicts with capitalism,” he said. “I understand it’s the system that we have agreed upon for the moment—hopefully that’ll change—but in that I really try to minimize the priority of that as far as sponsors and, you know, laser beams focused on your pockets all the time.”

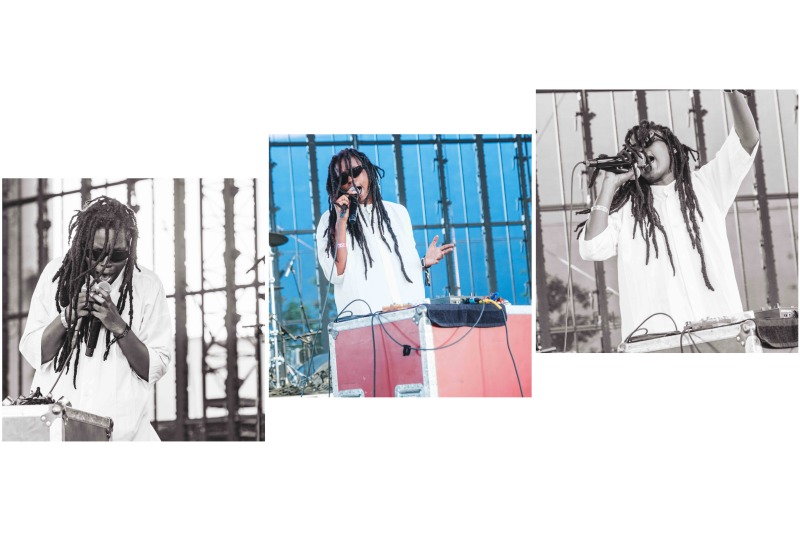

We agree that one of the biggest pitfalls of modern music festivals is that many of them feel so suffocatingly corporate that the musical aspect gets impersonal, almost incidental, in a way that highlights how “brand identity” is an oxymoron. “A corporation doesn’t have these qualities but you have originality, you have ambition, you have creativity, you have integrity,” Bunton said.“That’s why they’re paying you. You’re loaning that to them.” It’s something I’m thinking of during Moor Mother’s set of spoken-word poetry backed by cacophonous jazz rock. Cool as hell in a crisp white button down and dark sunglasses, she enraptures the midday crowd, intoning with a priestlike command about generations upon generations of inherited colonial violence and no one to take accountability for the ongoing legacy of bloodshed that the so-called civilized world is built upon; immeasurable pain with no where to go. It’s a moment of levity when, towards the end of her set, she says, “Shoutout to TV On The Radio for having TASTE, and for making good choices!” Good taste isn’t something you can buy. Good taste takes time. It takes curiosity and commitment. Developing one’s artistic sensibilities is an act of creation itself.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-