On The Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks

“…why…, it should be the greatest time of my life. Next letter from the road.”

One may read Oliver Sacks’ new autobiography with a regrettable and premature sense of sorrow. A column by the celebrated and accomplished neurologist from last February detailed the discovery of a terminal liver cancer, with only months to live. That now serves as a somber, auxiliary preface to this otherwise ebullient telling of a remarkable life.

Sacks assuredly outshines that sorrow with On The Move’s engaging narration and its easygoing frankness while unpacking personal details and some fresh insights gained from his earliest case studies.

Sacks assuredly outshines that sorrow with On The Move’s engaging narration and its easygoing frankness while unpacking personal details and some fresh insights gained from his earliest case studies.

Indeed, it is the sympathy with which he perceives the various encounters, experiences, the various people and patients, that gives his writing voice such a glow. The poet Thom Gunn told him as much, after reading his most famous work Awakenings, writing to him in a letter (published in Move,) that his sympathy “…is literally the organizer of your style…and is what enables it to be so inclusive, so receptive, and so varied.” Mr. Gunn sums up the experience of Move, also. Quite succinctly.

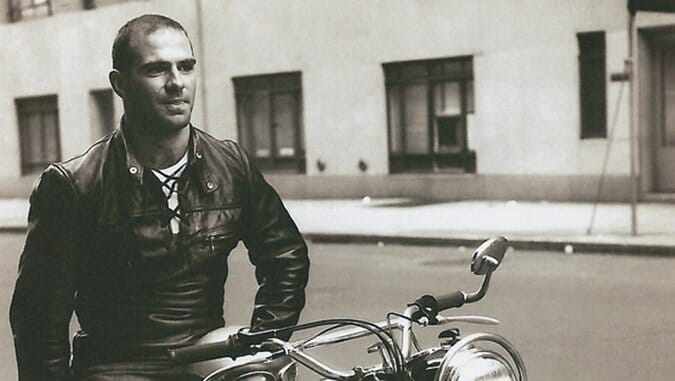

On The Move portrays the young man as bookish as he is virile, fueled by an adventurous hunger not just for the knowledge, but also an adventurous side eager to experience life to its fullest, to explore, to fall in love, to fully actualize himself and, above all, to write.

“Over a lifetime, I have written millions of words, but the act of writing seems as fresh, seems as fun, as when I started it, nearly 70 years ago…I suspect that a feeling for stories, for narrative, is a universal human disposition, going with our powers of language, consciousness of self, and autobiographical memory.”

This is the story, illuminated especially by revealing diary entries and the exchanges of letters between family and colleagues, of how he gained his famous intellect and honed his nuanced intuitions about the workings of the human brain that we all know him for, today.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-