Public Apologies Are Meaningless Theater

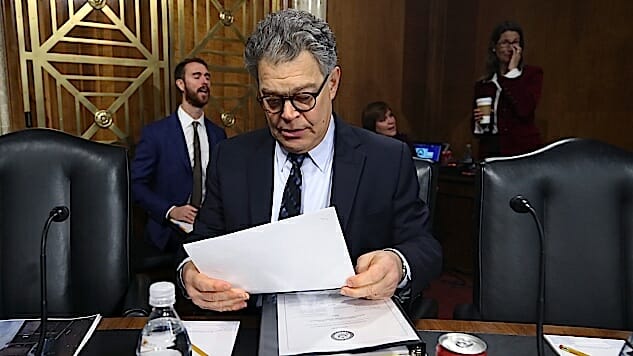

Photo by Mark Wilson/Getty

Earlier today, Sen. Al Franken (D-MN) was accused by former model and current radio host Leeann Tweeden of kissing her without consent during a USO tour, and groping her while she slept (there is picture evidence for the latter). Franken, who is also an author and former SNL writer, was johnny-on-the-spot with his public apology. It was a pretty good one, as far as these things go—he even called for an ethics investigation into his actions:

JUST IN: Sen. Al Franken delivers lengthier apology following accusation of sexual misconduct: “I am asking that an ethics investigation be undertaken, and I will gladly cooperate.” https://t.co/aDkmC6puqypic.twitter.com/668E3GrXci

— ABC News (@ABC) November 16, 2017

Now, an apology of this sort has some importance within the national dialogue, insofar as it’s a reminder that sexual assault is bad. That should go without saying in America, but considering the fact that we have a confessed groper in our highest office, it could stand a bit of emphasis now and again. Those who commit sexual assault should feel remorse, and the fact that they’re forced to apologize is a good lesson in public morality for everyone else. In that sense, the mere existence of the apology is beneficial.

But in terms of gaining an insight into the culprit’s true feelings, much less absolving him? The public apology is utterly meaningless, and so is the debate about which ones are “best.”

Too often lately—usually on Facebook—I’ve seen the following exchange, and it almost always takes place between a man and a woman:

Woman: That apology is not good enough.

Man: What else do you want? He took responsibility!

Woman: I want x, y, and z.

The man always comes off as the dolt in this scenario, and deservedly so, but they’re both making the same mistake. Namely, they are engaging with the idea that there exists some hypothetical apology which is sufficient.

The problem with that is that some people, even sexual abusers, are smart. They can demonstrate contrition, they can flatter the outraged by co-opting their language, and they can manipulate through the appearance of growth. Someone will always write the perfect apology. By the standards laid out in recent months, Al Franken came pretty close to pulling it off. He took near-total responsibility for his actions, blamed himself, and went on to say that other victims should be believed. In the future, he said, he would be an ally.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-