Robert Hunter: Not Playing in the Band

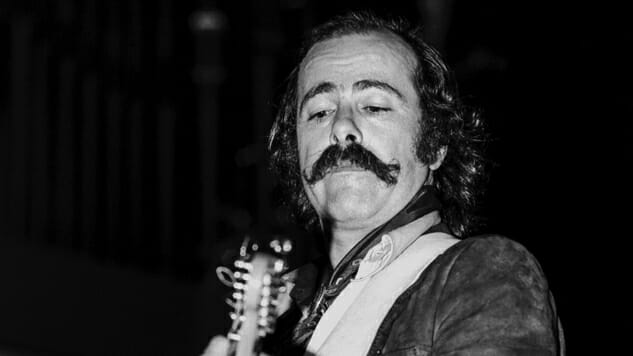

Photo by Ed Perlstein/Redferns/Getty

When the Grateful Dead were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, the individuals honored included 11 musicians who had performed on stage as members of the group and one person who’d never done so. That was Robert Hunter, the group’s off-stage lyricist, someone deemed so essential to the band’s achievement that he became the first non-performer inducted with a band into the Hall. So far, he’s still the only one.

There’s a reason for that. Very few people have held his job—writing lots of songs for a rock ’n’ roll band without joining them on stage—and no one has done it as well. Hunter’s words were the perfect complement for Jerry Garcia’s music, because they pulled off the same balancing act: remaining rooted in American traditions while at the same time imagining an alternate America for the near future. Take away either half of that balancing act, and the Dead’s songs are a lot less interesting. Take away Hunter’s lyrics and replace them with, say, Bernie Taupin’s lyrics, and the songs are also a lot less substantial.

Hunter, who died Monday night at home after recent years of spinal problems and surgery, didn’t write all of the Dead’s lyrics, but he wrote the bulk of them, including the words to such staples of the band’s live set as “Casey Jones,” “China Cat Sunflower,” “Bertha,” “Brown-Eyed Woman,” “He’s Gone,” “Tennessee Jed,” “Box of Rain,” “Cumberland Blues,” “Jack Straw” and “Sugar Magnolia.” The latter two songs were co-written with Bob Weir, but most of Hunter’s collaborations were with Garcia.

The two had met as teenagers in Palo Alto in 1961 and even formed a short-lived folk-music duo called Bob and Jerry. It soon became obvious that Garcia was a better singer and a much better musician and eager to get better at both, while Hunter’s heart was in writing, not playing. The duo bit the dust, but the friendship endured. And when Hunter sent his old pal some poems called “St. Stephen,” “China Cat Sunflower” and “Alligator” from New Mexico, Garcia told him to come back to the Bay Area and help write songs for his new band.

They weren’t a songwriting team like John Lennon & Paul McCartney, who both contributed words and music. Hunter & Garcia were more like Jerry Leiber & Mike Stoller or Richard Rodgers & Lorenz Hart, who practiced a sharp division of labor between lyrics and melodies. Sometimes Hunter would hand the guitarist stacks of paper with rhyming verses that Garcia would sort through till he found something he liked.

Other times Hunter would sit in on the Dead’s rehearsals and jot down lines in response to the vamps that came out of their jamming. “Goddamn, Uncle John’s mad,” he wrote during one practice session. No, that wasn’t right, he decided. How about, “Come hear Uncle John’s band.” Where could the band be heard? “Down by the riverside.” Why should you listen? Because we’ve “got some things to talk about here beside the rising tide.” That song, “Uncle John’s Band,” put the Grateful Dead’s artistic vision into words. It was as much the band’s theme song as “Hey, Hey, We’re the Monkees” was for another group.

Garcia’s lovely guitar tune pulled the listener in with a sing-along that recalled a rural church choir “down by the river” before the guitar solo spun off like a crop-duster plane doing loops over that creek. But Hunter’s lyrics brought the musical story into focus. He started out sounding like a town elder who warns, “When life looks like Easy Street, there’s danger at your door.” But he wound up sounding like the local shaman shambling in from a nearby cave to say, “It’s the same story the crow told me; it’s the only one he knows: like the morning sun you come, and like the wind you go.”

That song depicts a welcoming, supportive community, but Hunter was just as capable of describing a loner pursued by ex-lovers, the sheriff and the devil. That’s the story of “Friend of the Devil,” set to the tumbling music of Garcia in his bluegrass mode. The song’s narrator heads out from Reno, Nevada, and ends up hiding in the Utah hills, learning too late that you can accept help from the devil, but it always comes with strings attached. It was this ability to capture both the happy-go-lucky and angst-haunted sides of American life that gave Hunter’s writing its breadth and depth.

“Uncle John’s Band” first appeared on 1970’s Workingman’s Dead, and “Friend of the Devil” debuted later the same year on American Beauty. This one-two punch provided the Dead’s two best studio albums, which were followed in turn by the band’s two best live albums, 1971’s Grateful Dead and 1972’s Europe ’72. Also emerging in 1972 was the best solo album from the group, Garcia, which featured such classic Garcia-Hunter co-writes as “Deal,” “Loser” and “Sugaree.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-