Robert Hunter: Not Playing in the Band

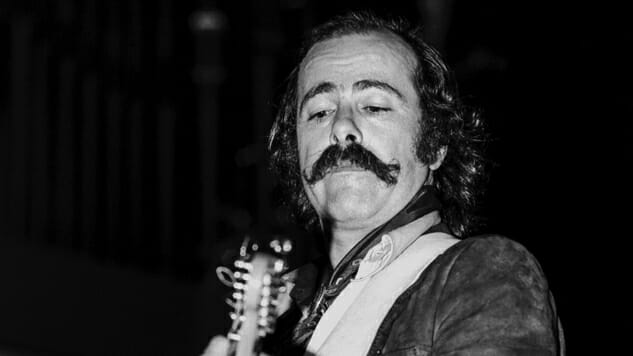

Photo by Ed Perlstein/Redferns/Getty

When the Grateful Dead were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, the individuals honored included 11 musicians who had performed on stage as members of the group and one person who’d never done so. That was Robert Hunter, the group’s off-stage lyricist, someone deemed so essential to the band’s achievement that he became the first non-performer inducted with a band into the Hall. So far, he’s still the only one.

There’s a reason for that. Very few people have held his job—writing lots of songs for a rock ’n’ roll band without joining them on stage—and no one has done it as well. Hunter’s words were the perfect complement for Jerry Garcia’s music, because they pulled off the same balancing act: remaining rooted in American traditions while at the same time imagining an alternate America for the near future. Take away either half of that balancing act, and the Dead’s songs are a lot less interesting. Take away Hunter’s lyrics and replace them with, say, Bernie Taupin’s lyrics, and the songs are also a lot less substantial.

Hunter, who died Monday night at home after recent years of spinal problems and surgery, didn’t write all of the Dead’s lyrics, but he wrote the bulk of them, including the words to such staples of the band’s live set as “Casey Jones,” “China Cat Sunflower,” “Bertha,” “Brown-Eyed Woman,” “He’s Gone,” “Tennessee Jed,” “Box of Rain,” “Cumberland Blues,” “Jack Straw” and “Sugar Magnolia.” The latter two songs were co-written with Bob Weir, but most of Hunter’s collaborations were with Garcia.

The two had met as teenagers in Palo Alto in 1961 and even formed a short-lived folk-music duo called Bob and Jerry. It soon became obvious that Garcia was a better singer and a much better musician and eager to get better at both, while Hunter’s heart was in writing, not playing. The duo bit the dust, but the friendship endured. And when Hunter sent his old pal some poems called “St. Stephen,” “China Cat Sunflower” and “Alligator” from New Mexico, Garcia told him to come back to the Bay Area and help write songs for his new band.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-