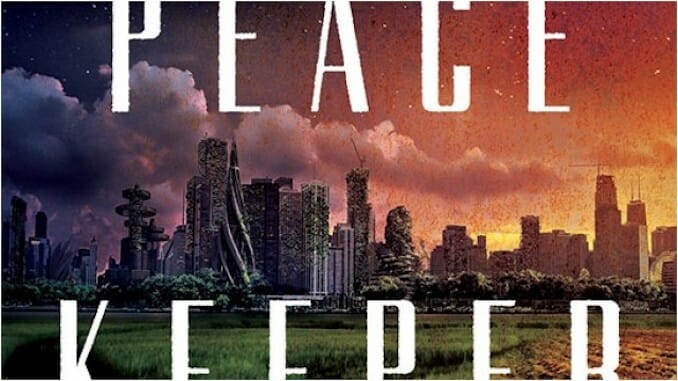

A Procedural Without Police: B. L. Blanchard’s The Peacekeeper

Detective novels and police procedurals have a long history in the mystery genre. But what happens when police as we know them don’t exist? In B. L. Blanchard’s debut novel The Peacekeeper, the first in her new “The Good Lands” series, the Americas were never colonized. Western ideas about law and punishment are foreign. Instead of Law & Order, Blanchard creates a world of Peacekeepers and Advocates, one that embraces the genre readers know and love while creating a strikingly fresh take on solving crime.

The Peacekeeper opens on the festival of Manoomin, a traditional celebration in the Anishinaabe nation, Mino-Aki. The people of Baawitigong, situated in the same location as our world’s Sault Ste. Marie, take their canoes out into the water and harvest wild rice, the way their ancestors have always done. In the modern era, the celebration is witnessed by tourists from all over the world: the Islamic Empire, the Aztec and Mayan nations, Europe, China, the Asante Empire, and more. And despite the festival marking the tragedy that took place in his family twenty years ago, Chibenashi, a Peacekeeper, is on duty, making sure that the peace is kept.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-