Author Daniel Wolff Talks Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie and an American Massacre

When 19-year-old Bob Dylan arrived in Greenwich Village in 1961 with a beat-up guitar, a whooping harmonica and an improbably craggy voice, he made no attempt to hide his total identification with iconic singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie. He imitated every aspect of Guthrie’s look and demeanor, from his clothes to the way he held a cigarette. Most of all, Dylan aimed to play and sing like Guthrie, though Village contemporaries like Dave Van Ronk quipped that Dylan’s imitation sounded more like the constricted voice of the dying Guthrie (then languishing in Brooklyn State Hospital) than the Dust Bowl balladeer whose voice rang out in the ‘30s and ‘40s.

More linked these two singer-songwriters than appearance and vocal timbre. In Guthrie’s songs, Dylan found not only lessons in how to be a folksinger, but secrets of how to live. Likewise, more set the two men apart than their initial pilgrim-meets-prophet encounters would suggest. It was the Huntington’s Chorea-afflicted Guthrie’s diminished state that gave Dylan some perspective on his hero. “Partly because Woody was sick, Dylan realized, ‘This is just another guy, not an idol, not a god,’” author Daniel Wolff told Paste in a recent interview. “And I think it both shocked him a little and set him free at the same time.”

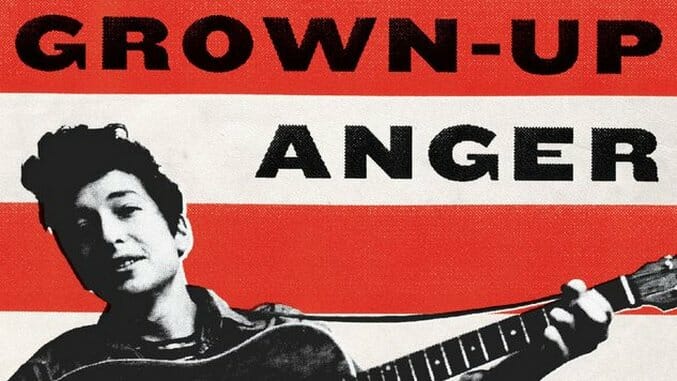

Wolff’s provocative new book, Grown-Up Anger: The Connected Mysteries of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Calumet Massacre of 1913, finds deeper connections in the rage that came across in their songs—and the threads of resistance that sustained the anger across generations. Wolff identifies anger as his own gateway to an expanded worldview when he was a 13-year-old, specifically through Dylan’s spiteful “Like a Rolling Stone,” the 1965 hit that made Dylan an unprecedented sort of pop star. To Wolff, it sounded “as if someone—Dylan—had found a crack in the surface of day-to-day life and pushed up through it, erupting.”

“Like a Rolling Stone” also sounded like the voice of a former Guthrie acolyte who had moved on. No longer was Dylan modeling himself on an Oklahoma native who once said the songs he’d written about Dust Bowl refugees “came from the Okies, not me.” Dylan had found an incendiary, idiosyncratic voice that survived his youthful infatuation with the Guthrie legend, and it resonated with an entire generation because it was so inexorably his own.

Grown-Up Anger digs deep into the inter-generational interchange of songwriters building on each other’s work. Even as he found his own voice, Dylan continued to weave melodies from the folk tradition into his work, going back at least as far as turn-of-the-century radical labor songwriter and martyr Joe Hill (even though he’d never identified with Hill as anything more than a precursor to Guthrie). Like Hill himself, Dylan often plied his trade by applying “new words to old songs.”

The song that established Dylan (however briefly) as the pre-eminent protest songwriter of his generation, “Blowin’ in the Wind,” appropriated the melody of the defiant slave song “No More Auction Block for Me.” It’s fitting, then, that “Blowin’ in the Wind” stuck in soul singer Sam Cooke’s craw so insistently as a song that a black man should have written that it motivated Cooke to write “A Change is Gonna Come,” the greatest song of the 20th Century.

In some of Grown-Up Anger’s most absorbing moments, Wolff delves into these connections and appropriations, revealing how songwriters of different eras built new songs on old ones. Particularly in songs associated with the labor and Civil Rights movements, Wolff explains, “They were very consciously saying, ‘Everybody knows this tune, so let’s use that, and then we’ll put lyrics on it that will help our cause.’ That’s the nature of art. You beg, borrow and steal to get something that works.”

At the heart of Grown-Up Anger is the melodic link that binds one of Guthrie’s most affecting compositions to one of the two original songs on Dylan’s first album, “Song to Woody.” As Dylan sings of a “funny ol’ world that’s a-comin’ along” and pays tribute to Guthrie, he does so to the tune of Guthrie’s “1913 Massacre.”

At the heart of Grown-Up Anger is the melodic link that binds one of Guthrie’s most affecting compositions to one of the two original songs on Dylan’s first album, “Song to Woody.” As Dylan sings of a “funny ol’ world that’s a-comin’ along” and pays tribute to Guthrie, he does so to the tune of Guthrie’s “1913 Massacre.”

Guthrie’s song, recorded in 1945, tells a decades-old story that he learned second-hand from Communist Party USA founder and tireless labor activist Mother Bloor. It explores a Christmas party for the children of striking immigrant miners in Calumet, Michigan in 1913 that ended in tragedy when man with a mining company pin yelled “Fire!” into the crowded upstairs hall where the party was happening. Though there was no fire, in the frantic rush down to the hall’s only exit, 73 people—including 60 children—tripped in the narrow stairwell and suffocated under a pile of bodies.

“1913 Massacre” reminds us of what we already knew: that Woody Guthrie could set a scene and tell a story with astonishing power (“There’s talking and laughing and songs in the air,/And the spirit of Christmas is there everywhere,/Before you know it you’re friends with us all,/And you’re dancing around and around in the hall.”). But it also reveals the anger that fueled Guthrie’s greatest songs—up to and including “This Land Is Your Land,” a bitter Socialist response to the imperial arrogance of “God Bless America”—but has been weeded out of his legend by those who prefer to remember Guthrie as a folksy patriotic pastoralist.

“I still find it astonishing that school kids learn ‘This Land Is Your Land,’” Wolff says. “I think if anybody really looked at that song, they’d go, ‘No, no, no. My kid’s not learning that.’ But I’m glad it happens. It’s a great American song. But that was part of the positioning of Guthrie during the Red Scare as neutral, just a patriot, all-American instead of a radical.”

“1913 Massacre” rails against the “scabs” and “copper boss’ thugs” and concludes with a couplet that captures Guthrie at his angriest, distilling the Calumet tragedy to its infuriating essence:

The parents they cried and the miners they moaned,

“See what your greed for money has done.”

Much as “1913 Massacre” is difficult to reconcile with the sanitized image of Woody Guthrie as an innocuous all-American balladeer, it also, to this day, remains a sticking point in Copper Country. Were the deaths at Calumet simply a tragic accident—or the largest unsolved mass murder in Michigan history? Excavating the history of the mine, the strike, the tragedy and the song, Wolff explains that Guthrie’s angry indictment of the copper bosses stands far afield from the official version of the event. Wolff describes the convoluted story that surfaced the day after the tragedy—absolving the mining company, and impugning union leaders for politicizing the children’s deaths—and held sway for 100 years.

“If nobody did anything wrong, then we can all forgive each other and move on,” Wolff says. “It’s like racial stuff in our country. Instead of confronting it and dealing with it, they wanted to sweep it under the table—‘Let’s move along here and not get worked up about this.’ And it struck me, when I finally read the books and did the research about it, how much of our history tends to work that way. ‘Let’s not get anybody upset here. Let’s not focus on anger. Let’s focus on reconciliation, even at the expense of truth.’”

To Wolff’s great credit, Grown-Up Anger does exactly the opposite.

A Grown-Up Anger Playlist

Grown-Up Anger evokes fascinating history, but it’s also a book full of songs that can’t be separated from that history. Even with a writer whose prose is as energetic as Daniel Wolff’s, words alone can’t fully evoke the songs whose infectious anger brought bitter history to life and compelled their listeners to action. As a companion piece to Wolff’s absorbing book, here is a Spotify playlist that expands on the story:

Steve Nathans-Kelly is a writer and editor based in Ithaca, New York.