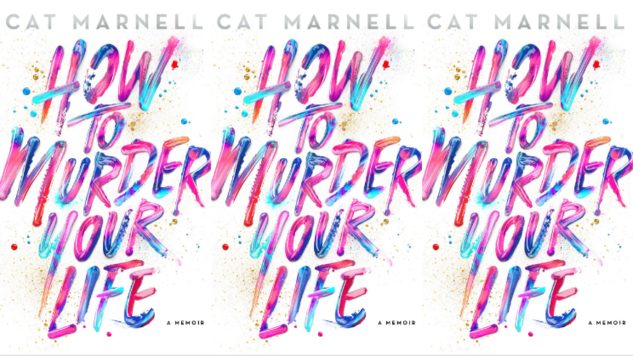

How to Murder Your Life: Cat Marnell’s Amphetamine Memoir and How We View Addicts

Press surrounding Cat Marnell’s book deal was dripping with venom. Yellow headlines blared—even a publication as august as The Atlantic couldn’t resist running the headline, “Cat Marnell’s Book Deal Could Buy a Lot of Drugs.” Then the book proposal’s contents were leaked, leading to ridicule and Marnell’s all-caps Twitter declaration that she hates herself more than we hate her.

The entire saga was laced with hatred, because although Marnell was achieving media success directly because of her sickness, she was not afflicted with something relatable like cancer. Her main condition, the least pitied of all pathologies, is addiction.

The whole thing seemed so evil I was moved to write an op-ed for The Myrtle Beach Sun News, defending her as a gifted writer, something ridiculous when the writer in question has signed a lucrative deal with a major New York house and something like “talent” is usually beyond reproach.

Her writing “attracted gallows watchers and pontificators, people eager to degrade or chide her for her actions or utilize her for ethical discussions centered on celebrity culture, confessional writers and our national obsession with the tragic,” I wrote. And they did this all the while denying the simple fact that she was not just an addict, but an addict with a voice. I’ve read thousands of words about beauty products I’ll never use, simply because she is that arresting of a writer. The idea of the good a voice like that could do for the addicted seemed lost.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-