“We’re Starting to Realize That You Can’t Ignore Race.” Celeste Ng Talks Her New Novel

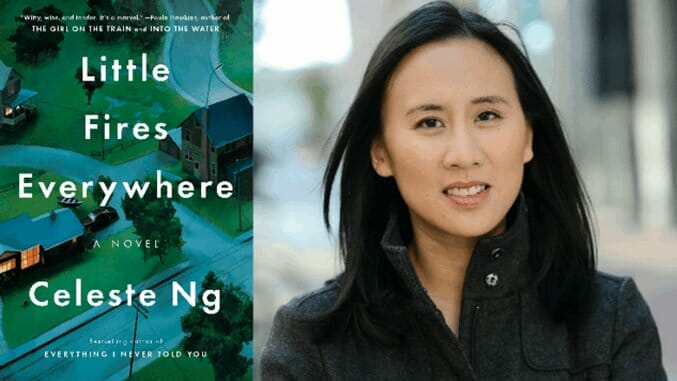

Author photo by Kevin Day Photography

Little Fires Everywhere appropriately begins with a blaze: “Everyone in Shaker Heights was talking about it that summer: how Isabelle, the last of the Richardson children, had finally gone around the bend and burned the house down.” After this explosive first line, author Celeste Ng then backtracks to reveal how a custody battle has pitted family members against one another (producing an arsonist in the process).

Following her acclaimed debut, Everything I Never Told You, in which a biracial Chinese-American family unravels after their daughter’s death, Ng has returned with a sophomore novel exploring racism, classism, privilege and family. “I’m really interested in how we understand each other, and whether we can understand each other,” she says in an interview with Paste.

And given our current events, Little Fires Everywhere couldn’t be more timely. When Ng began writing the book in 2015, she says, “We were in a very different political and cultural moment. And even when I sold the book, we were in the run-up to the election… So now it takes on a slightly different resonance.”

The novel is set in late-‘90s Shaker Heights, Ohio, an affluent planned community that prides itself on its progressive ideals and inclusivity. Ng, who lived there as a child, says she views Shaker Heights differently as an adult. “I can see the flipside of the idealism that drives the community, so I wanted to try and write about the complexity of that place. And I came up with this family, and I came up with this mother and daughter who come from out of town and stir up trouble.”

The mother, itinerant artist Mia Warren, and daughter, 15-year-old Pearl, disrupt the Richardsons’ picture-perfect family. Mia and Mrs. Elena Richardson become entangled in opposing sides of a bitter custody battle, fought between a Chinese mother who abandons her baby and a white couple who tries to adopt the child. Against the backdrop of this conflict, Ng examines the tension that builds from acting on one’s beliefs. “This is a debate that we feel a lot inside ourselves,” Ng says, “between having these ideals…and [doing] things to make the world better, and then the desire that we not upset the system that we’re in.”

On one end of the spectrum is Mrs. Richardson, who believes that the spark for social justice should be “carefully controlled.” On the opposite end is Izzy, the youngest Richardson daughter, who compounds her acute sense of right and wrong with an eagerness to see justice meted out. “Izzy is a teenager,” Ng says, “and I remember being something like that as a teenager; I had these principles and I wasn’t able to see the nuance in them.”

Between these extremes is Mia. “Mia, of all the characters in the book, has the most measured sense of what’s going on,” Ng says. “She’s still like, ‘I’m going to do this, but I just recognize that I’m going to lose this other thing.’”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-