Comic Book & Graphic Novel Round-Up (9/19/12)

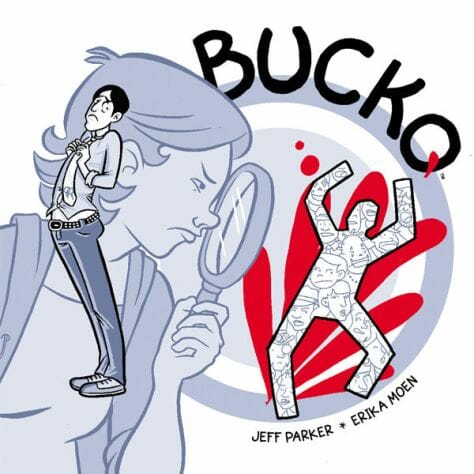

Bucko

by Jeff Parker and Erika Moen

Dark Horse, 2012

Rating: 8.6

Bucko is sort of a hipster Big Lebowski, a detective story that’s more about the journey than the solution and happy to meander, Raymond Chandler-style, picking up interesting characters along the way. Sure, it has cliffhangers, no doubt driven by its original publication as a webcomic, but it’s not a plot-driven enterprise. Rather than be annoyed at the lack of resolution, you’re sad when it draws to a close because it’s been so much fun. Jeff Parker’s filthy, inventive mind pairs nicely with Erika Moen’s gorgeously simple drawings as the sense of sweetness in the visuals cuts the acid of the writing, which spares no one. Usually, when someone’s referred to as an “equal opportunity offender,” it means a bunch of aggressive, loutish behavior, but Parker makes the description one to be proud of. Authors’ commentary at the bottom of each page is snappier by far than on any DVD I’ve owned and is a nice bonus for those who want the printed copy of Bucko. (HB)

Sword of Sorcery #0

by Christy Marx, Tony Bedard, Aaron Lopresti and Jesus Saiz

DC Comics, 2012

Rating: 6.3

DC Universe Presents #0

by various artists

DC Comics, 2012

Rating: 4.7

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-