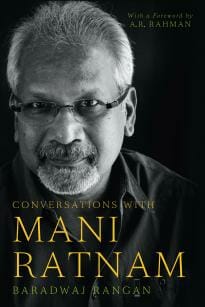

Conversations with Mani Ratnam by Baradwaj Rangan

Dancing with Shiva Bhakt

I’m at the laptop writing this review, and I’m trying to remember what I liked about Rangan’s Conversations with Mani Ratnam, a book I read many weeks ago. I’m distracted by the gyrating antics of my 12-year-old daughter, Amory, who is dancing to the TV. It may have been a mistake to sit in the same room. The objects of our attention, however, are related.

We live in Bangladesh. The music channel currently occupying my daughter’s attentions is not MTV or some other American music channel, but the Hindi Music channel … beamed straight from India where the hit songs from the latest movies play endlessly and, to my mind, without mercy.

I try to re-focus on the task in hand. What do I know about this book?

I know that Mani Ratnam is accredited with revolutionizing Tamil cinema and with altering the course of Indian cinema. He is one of only three Indian directors to have a film (Nayakan, 1987) listed in Time magazine’s All-time 100 Great Movies—despite never training to make movies. (Ratnam grew up on the fringes of cinema, but studied as an adult to be a management consultant.)

By fluke, Ratnam ended up working on a film project with two friends. That film never came to fruition, but cinema now had him hooked. Living a kind of bohemian existence and hanging out with other wannabe stars, he happened to be in the right place at the right time when he began writing his debut film, Pallavi Anupallavi (in English), in 1980.

He never looked back.

I also know that the biography’s author, Baradwaj Rangan, works as a well-respected award-winning film critic in India and teaches a course on cinema at the Asian College of Journalism in Cennai—right in the heart of the Tamil Film industry that Ratnam almost single-handedly revolutionized in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Conversations with Mani Ratnam started slowly. (Both interviewer and interviewee turn out to be shy, introverted types.) Rangan’s well-edited book keeps up a sense of fun and camaraderie between brilliant director and knowledgeable expert as it shows fascinating insights into the making of all Ratnam’s films.

Rangan gives a separate chapter to each of the director’s films (except the first four works, which he bundles into one chapter). With the consistent focus, conversations can twist and turn without rambling.

I do have qualms about Rangan’s style. He tries just a little too hard with the English language. Like many Asian writers who become fluent in the colonial tongue, he seems hell-bent on proving his mastery. In his introduction, Rangan refers to girls in Indian movies who “threatened to burst out of salwar kameezes glued to their zaftig frames.” I had to look up the word zaftig, which didn’t please me. If you’re interested, it means “full-figured body.” Fair enough, having watched many of these early Bollywood movies, but less pretentiousness would go a long way.

The author clearly admires Ratnam’s work. He treats him, in fact, with god-like awe in the introduction, disclosing that he grew up in the ‘80s admiring the director’s work. Referring to Idhayokoyil, Ratnam’s fourth and worst film according to the director himself, Rangan admits “I saw it three times.” So readers should not expect Rangan to be deeply critical here of the director … or to scrutinize his weaknesses. We get fleeting moments of critique, but generally we read an account of a student with his guru.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-