Cormac McCarthy: America’s Greatest Novelist Stumbles Back Into the Arena

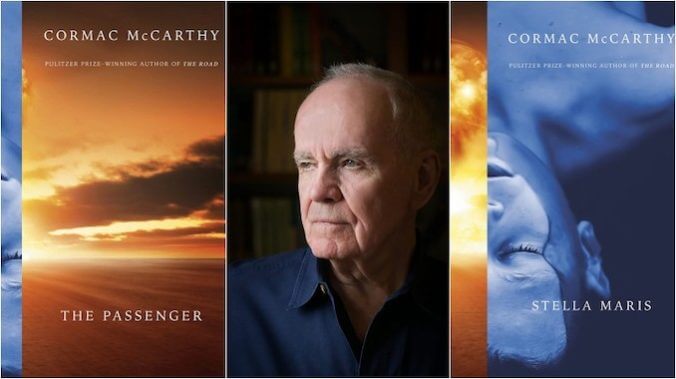

Photo: Knopf and © Beowulf Sheehan

Cormac McCarthy is one of America’s greatest writers—and with the death of Toni Morrison, probably our best living novelist and best chance at another Nobel Prize in Literature. After writing his five best-known—and, to my mind, best—novels between 1992 and 2006, McCarty published no fiction from 2007 through 2021 (just a screenplay and a philosophical treatise). Now he has reemerged with not one but two novels: The Passenger, published in October, and Stella Maris, published this month.

These volumes are obviously the work of a gifted prose stylist and a major thinker, even if they don’t quite work as novels, as such. I’m glad I read them, but I wouldn’t recommend them to anyone as a place to begin exploring McCarthy or his works. If, on the other hand, you’ve already read the bulk of his fiction, these late-career books offer some fascinating ideas and set pieces to chew on.

One of McCarthy’s great achievements as a writer has been his consistent ability to marry the two dominant strains in American literature. One is the maximalist voice of Walt Whitman’s “barbaric yawp,” of William Faulkner’s dizzying run-on sentences, of the pulpit oratory from preachers black and white, of the florid lyrics of Bob Dylan and Kendrick Lamar. Standing in stark contrast is the minimalist voice of Emily Dickinson’s distilled quatrains, of Ernest Hemingway’s concise sentences, of the terse responses from both cowboys and Indians out West, from farmers and woodsmen back East, of Langston Hughes’ pithy fables and John Prine’s deadpan songs.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-