Creation Stories by Alan McGee

Go Buy Some Leather Jackets

Indie labels have been getting a lot of ink lately, whether Stax in 1960s Memphis or 4AD in ‘80s England. These books come filled with agonized discussion of the conflict between producing the kind of music the label existed to create and making the money the label needs to stay in business. The conflict often ends up destroying the label, or diluting its legacy.

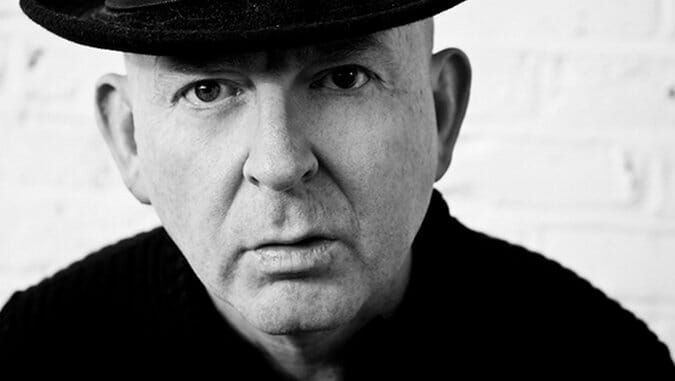

If the memoir of Alan McGee, the founder of Creation Records, gives any indication, his relationship with the market was different: he welcomed it as the ticket to the fortune, fame and drugs he always wanted.

This didn’t prevent him from putting out seminal indie rock by Jesus and Mary Chain and My Bloody Valentine. But he also made deals with and managed bands for major labels, cheered gleefully when the independent record distributor Rough Trade went out of business and worked with British rock sensations Oasis and the Libertines—very much mainstream acts.

McGee grew up in “dismal” and “angry” Glasgow. The tunes his parents played didn’t do it for him: “nearly all terrible.” He liked glam rock, but only singles—“albums were for grownups,” until he heard Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust.

Then along came punk, which “changed everything” for many musicians, listeners and critics in the ‘70s. McGee decided he had “no time to sleep if you wanted to get rich.” He moved out of home—because of a violent relationship with his father—and started playing in bands, setting up gigs and partying furiously. He liked running the show more than playing, so he channeled his efforts in that direction and founded Creation in 1983.

A strange coincidence brought McGee into contact with the Jesus and Mary Chain, one of his first successful rock bands. JAMC sent a demo to the musician and producer Nick Lowe. The back of the demo happened to hold a bootleg from Pink Floyd founding member Syd Barrett. Lowe played the Barrett for a close friend of McGee’s—Bobby Gillespie, lead singer of Primal Scream, a band that later hit it big on Creation with the 1991 album Screamadelica.

Gillespie also happened to like the JAMC demo, so he told McGee about it, and the Scotsman signed them up, excited that their level of “feedback was outrageous.” He helped the band become equally wild in other ways, playing purposely short gigs, inciting the occasional crowd riot, and generally gaining a lot of notoriety.

Any indie label has to solve a distribution problem. With limited access to consumers, how can you sell enough albums to cover costs? A label like Stax partnered up with a national behemoth, Atlantic records.

Initially, Creation had a different option: Rough Trade. “We could take them [recordings] into the shop and he’d [Geoff Travis, Rough Trade founder] get them out across the country for us… The Cartel was a collective of shops that offered small bands a genuine alternative to major label distribution… Rough Trade distribution… was completely idealistic and ultimately it failed but for a while it changed the landscape of British music.”

Independent happened to be less a statement of preference for McGee, more an economic necessity. “We weren’t interested in pleasing the indie purists,” he writes. “The whole indie thing wasn’t a philosophical choice. We recorded on a budget because that’s what we had to work with, and we were lucky that it suited a lot of our bands.” When Creation’s contract with Rough Trade ran out, “they used that as an opportunity to try to raise the percentage they charged,” so he “signed with their main rival Pinnacle.” Later, when he got better known, he’d partner up with Sony.

By his own account, McGee spent most of his time as a combination of jerk, junkie and crazy man. He characterizes hang-out sessions with the members of Primal Scream as “black humour, sarcasm, and sheer verbal nastiness.” He often drops an aside like, “I was horrible about him in interviews when I was a loudmouth drug addict.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-