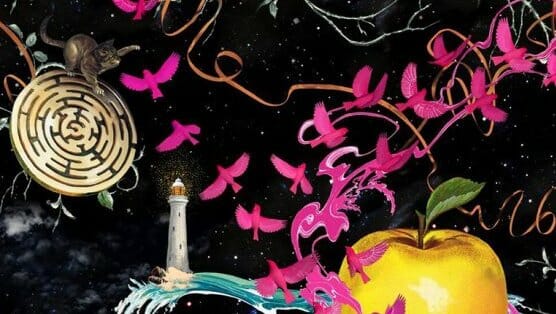

The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell

David Mitchell has built himself a reputation for masterpieces.

At once the student of time who wrote the swirling classic Cloud Atlas and the adept humanist behind the bildungsroman he called Black Swan Green, Mitchell’s intricately woven plots have made his name synonymous with the modern novel and earned him a John Llewellyn Rhys Prize and a spot on the TIME 100 list in 2007. With these accolades under his belt, Mitchell sets off to combine talents for metaphysics and humanism in his latest novel, long-listed for this year’s Man Booker Prize. The resulting romp through time and space ambitiously adds to Mitchell’s oeuvre.

The book begins by painting an almost Murakamian portrait of protagonist Holly Sykes against a backdrop of otherworldly chaos. The narrator changes with every chapter to come, but our introduction to Holly comes from the 15-year-old basket case herself. Holly relates the story of her time as a teenage runaway and, hardly a dozen pages in, first props appear for the supernatural epic destined to detonate later in the story.

The novel skips across the years, each new decade offering a different man in Holly’s life the chance to tell his story. Cambridge student Hugo Lamb relates a tale of financial cunning and collegiate fun that ends in Switzerland after a passionate one-night stand with Holly. In a section reminiscent of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, Holly’s partner Ed Brubeck recalls his traumatic experiences as a war reporter in Iraq. Washed-up novelist Crispin Hershey overcomes his sardonic jealousy to become an endearing character and a good friend to Holly. Each chapter provides a satisfying story on its own, but when pieced together, these varied vistas paint the life of Holly Sykes with a depth no single perspective could create. She plays both major and minor roles, both friend and rival. In the end, she becomes the most three-dimensional character in any of Mitchell’s novels.

Underneath each of these stories runs a conspicuous stream of oddities: precognitive episodes in which Holly steals a glimpse of the future; mysterious “daymares” lived in terror and then redacted from memory; a Miss Constantin, who continues to reappear but never ages. Supernatural events pop up time and again without explanation—all orbiting mysteriously around Holly Sykes like doomed satellites waiting to crash through the atmosphere.

Crash they do. In the book’s longest section, we enter the wise mind of a character named Marinus and her world of Horology. Holly takes a temporary back seat as supernatural undercurrents breach the surface and flood pages with a war between two factions of immortals. The Horologists, whose souls passively rebirth into a new body after death, face off against the evil Anchorites, whose quarterly human sacrifices grant them eternal youth. A page-turner erupts when Harry Potter-esque psychoduels rage between the forces of good and evil.

By introducing these two flavors of immortality, Mitchell brings to the forefront the novel’s persistent conflict: Aging vs. Tradition. Characters simultaneously fear the ravages of time, and wonder over threads of art and family that weave through history to unite us with the ancients.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-