Denis Boyles Highlights the Real Life Drama Behind the Encyclopædia Britannica in Everything Explained That Is Explainable

Denis Boyle’s Everything Explained That Is Explainable almost reads like fantastic fiction. The book drops you into a time when print publishers possessed the same dynamism as today’s web developers and authors celebrated as much fame as prime time pundits. And while we often romanticize the post-industrial years when the printed word was crucial to civilization’s advancement, Boyles highlights how lucrative publishing could be—despite squabbling between the major players involved.

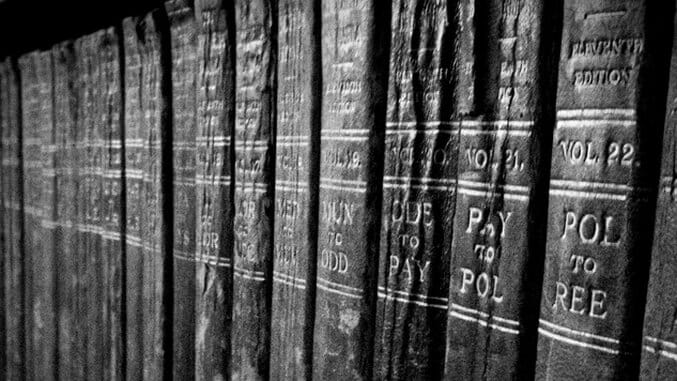

Chronicling the late 1890s and early 1900s, Boyles’ book tackles the dramatic events leading up to the Encyclopædia Britannica’s Eleventh edition’s release. For children of the ‘80s or ‘90s, it’s crucial to understand the reverence heaped upon this text. It was considered the last of the great scholarly encyclopedias, aspiring to report on “everything” and explain it to a growing population of literate readers. Boasting over 1,500 contributors, including Charles Darwin, the Eleventh edition promised unprecedented access to the foremost scholars of the time.

Boyles’ engaging narrative follows a handful of eccentric individuals responsible for the edition’s publication, revealing the decade-long drama behind the scenes. Paste caught up with Boyles to discuss the book’s colorful cast, the legal battle plaguing the Eleventh edition and people’s reactions his research.

![]()

Paste: What was it about the people involved in the project—a reporter, a publisher, an ad-man and an editor—that you found most fascinating?

Paste: What was it about the people involved in the project—a reporter, a publisher, an ad-man and an editor—that you found most fascinating?

Denis Boyles: They seem like such an unlikely ensemble—a group of people who might have populated a sitcom as easily as a serious publishing project. The Oxford scholar (Hugh Chisholm), the American huckster (H.E. Hooper), the bohemian ad-man (Henry Haxton) and the steady, insightful chorus, played by Janet Hogarth, whose life reads like a map of the Edwardian era and who is, to me, the most endearing.

Paste: You write that literacy at the “turn of the century not only opened minds, but it opened pocketbooks.” The publication game back then seems as wild and unpredictable as certain aspects of our economy today.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-