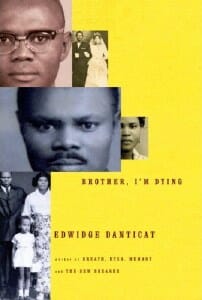

Edwidge Danticat

Heartbreaking account of Haitian immigrant coming to terms with her uncle’s cruel fate

Late in this memoir, acclaimed Haitian writer Edwidge Danticat describes her father’s dismay that the body of his brother—who has died unexpectedly and under deplorable circumstances in Florida—would not be returned to their home in Haiti.

“He shouldn’t be here,” Mr. Danticat (whom everyone calls Mira) protests tearfully. “If our country were ever given a chance and allowed to be a country like any other, none of us would live or die here.”

Earlier in the book Danticat had painted a more harmonious relationship between her family and the United States, where several members have naturalized. But as every immigrant knows, the difference between success and happiness in a new place depends on the gulf between wanting and needing to be there.

Immigration is less about choice when you’re from a country like Haiti, which foreign-policy wonks constantly remind is “the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.” Guyana, the country on the tip of South America where I grew up, has a slightly elevated status, considered among the poorest of the Western Hemisphere. However, its core problems, related to economic stagnancy and political turmoil, mirror Haiti’s, so I’ve always felt a kinship with Haitians. Both countries suffered massive brain drain as many of us citizens—faced with the prospect of never realizing even modest goals—steeled ourselves for adversity and snow, and determined to amount to something more somewhere else.

When Mr. Danticat says, “a country like any other,” he is undoubtedly thinking of the U.S., which is why many of us have made the necessary sacrifices to get here. We live in limbo between “Here” and “There,” clinging precariously to the beliefs and traditions that shaped us back home. Our achievements here are footnoted with “if onlys” there: If only our countries didn’t suffer from racist foreign policy or from greedy, corrupt, often violent, leadership, we could’ve done the same thing there.

In recent years, few voices have been as eloquent as Danticat’s in explaining the dichotomies of this hybrid American life. Her bestselling ?ction about Haitians and Haitian-Americans provides empathetic comfort to readers like me who have similar histories, and insight to others who can’t quite grasp why we continue to leave the tropics for concrete cities. For Haitians in particular, Danticat, 38, has taken on the task of literally rewriting their image in America, exposing the racist inaccuracies of the “boat people” persona that has been thrust upon these immigrants in this country.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-