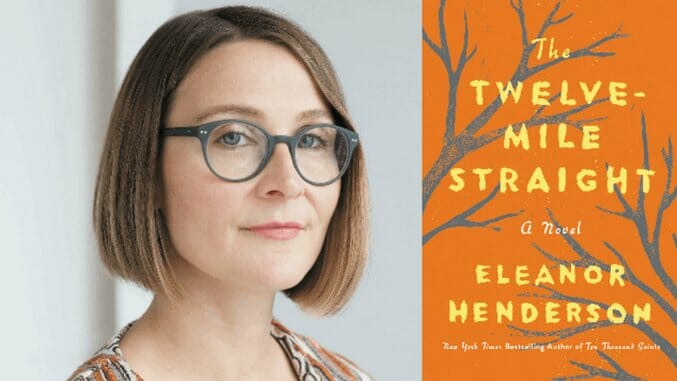

Eleanor Henderson Talks Jim Crow and Twins with Different Fathers In The Twelve-Mile Straight

Author photo by Nina Subin

“Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced,” James Baldwin once wrote. Trying to change a country in the midst of the most aggressive resurgence of white supremacist groups in 100 years is too tall an order for any novelist; just facing it is daunting enough.

Eleanor Henderson has broken new ground with her searing novel The Twelve-Mile Straight, which begins with the lynching of a black farmhand for the alleged rape of a white woman in 1930s Georgia. As Henderson began to write the book, she wondered, “Who needs to read another book about the Jim Crow South?” Over the years she spent researching the period and writing the novel, she found that, as she told Paste in a recent interview, “the kinds of mob violence and injustice that I write about in the book, that I hoped were shelved in the archives, are now in daily newspaper headlines.”

Henderson’s confessed “personal obsession” with the segregation-era South began with her father’s stories of growing up in a family of white sharecroppers in Georgia in the 1930s. She also gleaned much insight from Arthur Franklin Raper’s The Tragedy of Lynching (1933)—a jarring, almost-real-time study of America’s 20 documented lynchings in 1930—and The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson’s watershed 2010 book on the Great Migration and the brutal social and economic conditions that drove six million African-Americans out of the South between 1916 and 1970.

The incident that stirs a Cotton County, Georgia mob to racial violence in the opening pages of The Twelve-Mile Straight is the phenomenally unlikely birth of twins, one black and one white, to Elma Jesup, the daughter of Juke, a white sharecropper and moonshiner. The white twin presumably belongs to Freddie Wilson, her rogue fiancé, grandson of the man who owns the cotton land the Jesups work. The presumed father of the black twin is Elma’s father’s hired hand, Genus Jackson, who lives in a tarpaper shack on the same farm. Though Jackson insists he’d sooner lay with Juke Jesup’s mule than his daughter, mob rule prevails and the lynching is on.

Although Henderson’s intricately wrought re-creation of 1930s Georgia, with its layered racial and economic caste systems, draws heavily on extensive archival research, the captivating medical mystery at the heart of the novel comes from a more unlikely source: the author’s longtime love of TV soap operas.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-