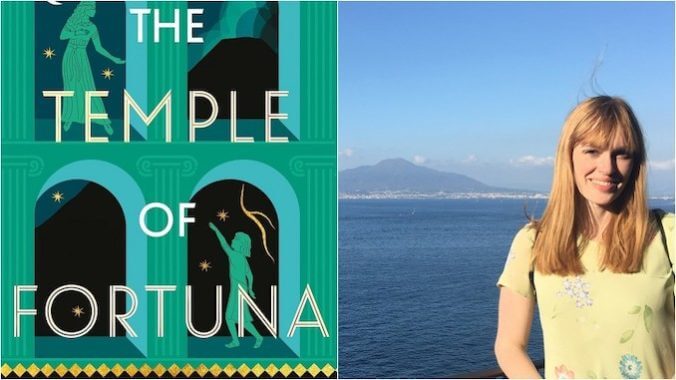

Elodie Harper Talks The Temple of Fortuna, Vesuvius’s Eruption, and Bringing the Wolf Den Trilogy to an End

Elodie Haper’s The Wolf Den trilogy is an impressive piece of historical fiction. Beautifully written and deeply researched, it unspools a tale of ancient Rome that manages to feel thoroughly modern, wrestling with issues of agency, morality, and female rage that will feel all too familiar to contemporary readers.

The series follows the story of Amara, a Greek girl sold into slavery after her father’s death and forced to work at a Pompiian brothel in the shadow of Vesuvius. Thanks to her indomitable spirit and seemingly bottomless fury at her circumstances, she schemes, fights, and manipulates her way from the lupanar to the streets of Rome itself, a freedwoman with a fortune of her own. But when events in the series’ third novel, The Temple of Fortuna, force her to return to Pompeii, she’s forced to face the family she left behind and forge a new future in the aftermath of one of history’s worst disasters.

Full of compelling characters, a few famous faces from history, and realistic, lived-in details that bring the past to vibrant life, Harper’s trilogy is excellent from its first page to its last, and a great example of the sort of story we need more of in this genre space. We had the chance to chat with Harper herself about finishing Amara’s story, why we’re all obsessed with the Roman Empire, and what’s next for her as a writer.

Paste Magazine: First, congratulations on finishing the Wolf Den trilogy! (You already know that I loved it.) How does it feel to have completed Amara’s story?

Elodie Harper: Thank you! I think it’s only just starting to sink in that the trilogy is finished. For so long I was so focused on getting the finale right, I didn’t stop to think about how I would feel afterward, beyond relief. But writing the final line did feel emotional; I finished edits on the whole book before writing the epilogue and so the very last line of the whole trilogy is also the very last line that I wrote.

Paste: I thought of you and your books immediately when that “men are secretly obsessed with the Roman Empire” business was going around. As someone I know is actually obsessed with it, what do you think it is about this time period that still keeps people so fascinated today?

Harper: I think there are aspects of the Roman Empire—its centuries-long military dominance for instance—which can seem stereotypically macho, hence the idea that all the guys are out there obsessing about legionaries and gladiators. But the Romans are also unique, I think, in their strange combination of being both very distant and very familiar.

In many ways, some of their social attitudes and technology (indoor heating and plumbing etc) can seem more modern than later time periods. Reading Latin authors like Catullus or Ovid, with their colloquial language and preoccupation with romantic love, relationship drama, parties, and sex, feels infinitely more contemporary than later writers in Medieval Europe who were hugely preoccupied with religious doctrine and sin. In other ways though, the Romans are utterly alien—their baffling religious cults, their punitive legal system, their use of slavery. This combination of being both modern and ancient makes them particularly fascinating.

Paste: I feel like the titles of both The Wolf Den and The House with the Golden Door are fairly self-explanatory—why The Temple of Fortuna? Tell me a little bit about what that, as an image and as a location, means to this story.

Harper: It’s a title that is both literal and metaphorical in relation to the book. Amara visits several temples to the goddess Fortuna in the story, two of which are real temples whose ruins are still standing in Rome and Pompeii. The first was a temple to Fortuna in her guise of controlling ‘the luck of the day’ and was also treated rather like a fashionable art gallery. The temple’s colossal cult statue of the goddess herself—or fragments of her—is in a museum in Rome. Her giant head survives and when I saw her, I was unnerved by her expression of power and indifference.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-