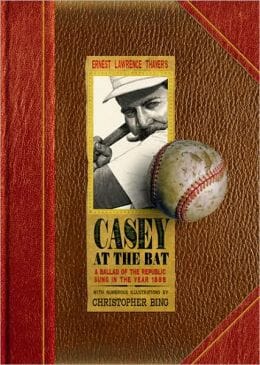

“Casey at the Bat: A Ballad of the Republic Sung in the Year 1888” by Ernest Lawrence Thayer

A bad stick man

The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville Nine that day;

The score stood four to two, with but one inning more to play,

And then when Cooney died at first, and Barrows did the same,

A sickly silence fell upon the patrons of the game.

Paste reader, these first lines come from “Casey at the Bat,” maybe the best-known poem in American literature…and most certainly among our best-known comic poems. For now, consider these opening lines a warm-up pitch, a practice swing.

Let me also throw a high hard surprise under your chin. You won’t believe it, surely, if I tell you this rollicking poem about baseball and hubris and dashed hopes issued from the pen of a philosophy major…and a former editor of The Harvard Lampoon?

With the poem’s publication in the San Francisco Examiner in 1888, Mighty Casey strode into the dugout of Americana to sit on the pine bench of legend right alongside Davy Crockett and John Henry and Annie Oakley and all those other American myths created or perpetuated by our able yarn-spinners and storytellers.

With a poem so well-known, you’d think the writer would be a household name—a Robert Frost or T.S. Elliot or even an Emily Dickinson.

Not so.

Ernest Lawrence Thayer was born in a town bearing his middle name, Lawrence, Mass., and he grew up a New Englander, true and blue. At Harvard, he took a magna cum laude in, yes, philosophy, then William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper plutocrat, hired him to go west, young man, and write for the San Francisco Examiner.

Thayer took New England with him. While working on the West Coast, he wrote and published under his college pen name, Phin, as in Phineas. (The affected appellation may come from Phineas Finn, the second novel in Anthony Trollope’s Palliser series.)

The West Coast proved good to Phin. At just age 25, he penned a poem of an over-proud baseball slugger with the hopes of 5,000 citizens of Mudville pinned to his big bat. The poem leaps from the page, in a galloping meter and rhyme meant as much for the ear as the eye.

Thayer, or Phin, as it were, wrote the poem about a baseball archetype, the kind of big bruising haughty slugger on most every baseball team, a beast strong enough to grind sawdust from a bat handle as he takes his grip, then win a game with a single swing…if he connects.

Every baseball fan knows the type—hitters like Barry Bonds in his day or Miguel Cabrera today, those feared princes of the batters box. In mythology, such sluggers swagger and strut to the plate. They send outfielders to new positions on the warning track. They back up infielders so deep they turn into outfielders.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-