Falling in love and following along with romance tropes already inspire that swept-away feeling of being on an epic adventure of the heart. But the growing subgenre of fantasy romances maps those swoony beats onto grand stories of magic and murder, kidnappings and sabotage. In these books, the fates of kingdoms or magic itself are nearly as important as whether the love interests will finally kiss and/or declare their love.

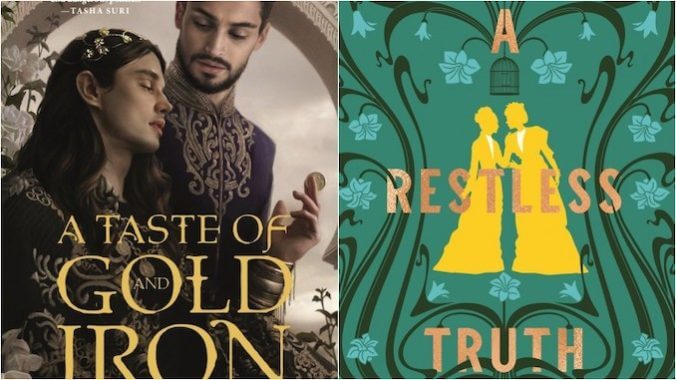

This Fall, authors Alexandra Rowland and Freya Marske both released queer fantasy romances: In the secondary fantasy world of A Taste of Gold and Iron, fretful prince Kadou must battle anxiety attacks as he investigates a counterfeiting conspiracy, while developing a better understanding of the reciprocal relationship between himself and his stoic bodyguard Evemer. Set in an alternate Edwardian England, A Restless Truth carries on the mystery of missing magical artifacts from A Marvellous Light, with determined Maud Blyth embarking on a maiden voyage of sexual self-discovery with rakish actress Violet Debenham while investigating a murder at sea. Despite their contrasting plot elements, these romances are in clear and fascinating conversation, which comes as no surprise considering that Rowland and Marske make up two-thirds (with Jennifer Mace) of the Hugo Award-nominated podcast Be the Serpent.

While the podcast is currently on hiatus, that break was our gain, as we were able to engage the two in familiar, delightfully intelligent banter—albeit via email instead of on-air—about bathhouses as pivotal romantic settings, using magic to strip away layers (emotional ones) or reaffirm loyalty, and how to write a scene to move the plot and the love story along at the same time.

1.) Great symbolism! You’re in transit from one place to another; and from one state of being (pre-falling in love) to another (transformed by love).

2.) Water metaphors!! I want Alex to talk more about this, as I know they use it deliberately to great effect.

3.) When things go terribly, a character can think about flinging themselves overboard to escape their feelings.

Rowland: Aw, thanks!

Marske: Unfortunately I decided to use my bathhouse as the setting for one of Maud and Violet’s two major fights, so there’s no tender hairwashing involved, but someone does get shoved up against a pillar and they are wearing bathrobes and are all pink and flushed and sweaty. So, you know. We’re halfway there.

(The other part of this answer is that when researching the Titanic, I ran across some gushing descriptions of the ship’s Turkish baths, and decided it was much too fun not to include. The entire book taking place on a single ship meant I had to grab at any potential settings more interesting than ‘the deck’ or ‘a cabin’.)

Rowland: The thing about bathhouses is that they’re a prime location to increase physical proximity and intimacy. Like I love the “forced proximity” trope as much as anyone, and I know Freya’s out here serving delicious feasts of that trope as she locks her characters in various confined spaces until they have Sexy Feelings about each other—it’s an invaluably useful trope for getting two stubborn characters over that initial hill so that they start noticing alluring things about each other!

But when the characters put themselves in that situation on purpose with their eyes open? When they walk into it knowing that they’ll be required to bare themselves, both figuratively and literally, to the other person, and they do it anyway? Oh deliciousness! Yes, yes, submit to that Mortifying Ordeal of Being Known!

And then of course, as Freya mentioned, bathhouses also provide a wealth of opportunities for washing each other’s hair or other forms of non-sexual but eye-wateringly intimate touch. Basically, if there’s a bit of machinery you need to make the engine of the romance run like it’s supposed to, bathhouses are your local makerspace fully stocked with all the tools you could possibly need to get it done.

Paste: Freya, you’ve described A Restless Truth as “lesbian Knives Out on a boat”… and then Rian Johnson dropped Glass Onion, a.k.a. Benoit Blanc investigating a murder on a cruise ship, with none other than Janelle Monáe! Will you be suing for damages? Are you and Rian Johnson narrative accomplices? What murder should Maud and Benoit team up to solve next?

Marske: I will magnanimously allow Rian Johnson to keep his idea, if only because I believe the world can’t have too many murder mysteries set on cruise ships. The locked-room isolation of it all! The forced proximity with strangers! That inbuilt symbolism of transitional states! (I toyed with the idea of asking if we could use “Do you think death could possibly be a boat?” from Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead as an epigraph.)

And the mind boggles at how much chaos Maud and Benoit Blanc could cause as a team. Both of them are prone to gleefully exploring tangents and prodding everyone around them into exasperation, fury, or fondness. I think they would be ultimately successful in solving the mystery, but the trail of semi-deliberate devastation left in their wake would be enormous.

Paste: What are some misconceptions about fantasy romance?

Marske: I feel like I’d be outright guessing or creating strawmen to whack in trying to answer this, as I’ve managed to curate my writerly spaces to be full of people who love fantasy romance or at least can see why other people love it! I don’t know what the other side of the internet is saying and [hairflip] I don’t care to know.

Rowland: Hard agree. [also hairflip]

Marske: I will say that if you’re a fantasy writer hoping to promote your work in capital-R-genre-Romance spheres: respect the history of that genre, respect the requirements of that genre (happy endings only!) and don’t assume that you’re inventing something from scratch just because you’ve never seen it on the SFF shelf before. Romance has been doing the work for decades.

Rowland: I think the only thing I would add to this, as Freya is as per usual being extremely correct about everything, is that one misconception I have seen about it is from unpublished authors who are writing fantasy romance. It seems like many of them think nobody cares about fantasy romance and that the thing they love won’t ever get an agent or get published. My darlings, no!

We don’t have space here to get into all the nuances of the traditional publishing industry, but please do not ever let a factor like that discourage you from writing the stories that bring you the most joy. The industry is not a static thing, it is constantly changing and growing—all it takes is one person writing something weird that isn’t getting published much and getting their foot in the door, and then another person with the same kind of book also wedging themselves in beside the first, and before you know it, a third person has a BIG HIT with their version of the weird thing, and suddenly it’s “trendy” and everyone’s doing it. You might not hit the NYT bestseller list with your book, but you might help get the door open a little farther for the next person. Takes a village, you know.

Paste: How do acts of magic (for example, touch-tasting or cradling) play into the romance in your books?

Marske: In A Restless Truth, the act of cradling has less weight within the romance than it did in A Marvellous Light. What’s important in this book is the kind of magic that Violet prefers and is expert in: creating illusions. Maud and Violet’s love story is a romance between someone who hates lies and deception, and someone whose magical expertise is all about creating beautiful lies. The war between delight-in-beauty and distrust-of-deception is the central tension of Maud’s feelings, and Violet’s hesitation to show the truth of herself is the central tension of hers.

Rowland: And for Kadou and Evemer, the major themes of both the book as a whole (i.e., the coin-counterfeiting plot) and their romance in particular are very much concerned with fidelity, oathkeeping, trustworthiness, and certainty in all of the above: A coin is an oath, a promise of value; the magic system means that if you touch a metal object, you know what metal it is. So the magic is symbolizing an external expression of what Kadou and Evemer are going through with first their fealty relationship and then their romance. It’s about knowing, beyond a shadow of a doubt, what someone’s made of.

Paste: Both couples also fall into the seductive magic of acting out dramatic stories, from epic oaths about royalty and protectors to penny dreadfuls. How does this complicate things?

Marske: Drama begets drama! And in the case of Violet and Maud, as silly and fun as the erotica-reading scene is, that openness about sex—the ability to put sex into words—creates a space for Maud to be able to talk frankly about her desires, and also creates an atmosphere of play which is very important. The sexual tenson in a romance should be unique to the characters involved, and this particular romance is about freedom and discovery.

Plus, the frame of ‘acting’ allows that lies-and-disguises theme to shine through at the same time.

Rowland: For Kadou and Evemer, I’d say that it actually simplifies things for them. All the stories about fealty and courtly love that they both hold so dearly give them archetypal Ideals to aspire towards and model themselves after, which gives them an ethical framework for how to see the world. It gives them a script for Correct Behavior, in other words—and they’re both quite happy to have this script and have found that it has served them well throughout their lives. Even Kadou is relieved to have such a script, because he knows that if he can trust the stories of what makes a Good Liege Lord, he doesn’t have to have such severe anxiety about what he’s doing and how he’s moving through the world.

The trouble comes about when the story and the archetypes and the Ideals stop serving them well, and they decide to act as individuals—selfish and imperfect and complicated, because it means they get to be in love. The story worked really well when they only needed a big-picture guide for how to run their lives, but when the scale is narrowed down to “two people who want to be together” rather than “an entire goddamn country”, it falls apart.

Paste: The way that Kadou handles his anxiety feels like it echoes the high emotions of falling in love: the relief that something is happening (even if it’s awful) because then you know how to handle it; what you think is happening versus what is actually happening. Was this intentional?

Rowland: Well, sort of, but I think you’ve framed the question around symptoms rather than the underlying shared cause, which is just that brains are weird and bad sometimes, and that everybody is an unreliable narrator to some degree, even when we’re trying hard to tell the absolute truth, because we experience the world through the lens of our own perceptions.

Big emotions like falling in love or flare-ups of chronic anxiety distort the lens. It is impossible for anyone to be a perfectly objective observer—that’s why good scientists put so much rigor into designing experiments that reduce bias as much as possible. So the intentional choice wasn’t about the anxiety mirroring falling in love, it was about showcasing the ways anxiety lies to you, which coincidentally happens to be a brain mechanism that is identical to how that first rush of infatuation lies to you.

Paste: One thing you don’t always see in romance is one of the protagonists having an established sexual relationship with someone other than their love interest, but both of your books open with one member of each pairing in a bit of a friends-with-benefits arrangement (or starting one up again). How do you balance portraying protagonists who clearly have a healthy sense of their sexual desires with the burgeoning chemistry (and love!) they develop with the other protagonist?

Marske: When we meet Violet, her previous casual-but-friendly sexual relationships represent the healthiest relationships she’s had in her life; she’s reacting pretty hard to a failed episode of romantic love. But she had a similar upbringing to Maud—very proper and constrained—and fondly remembers how satisfying it was to rebel through sexual discovery. I wanted to show sex as a positive force in both of the main characters’ lives, and not something that always has to hold great significance or necessarily lead to romance.

Of course, given that this is a romance, “I can definitely give this beautiful girl sex lessons without developing feelings, for sure, no WAY will this go wrong” is a deliciously doomed endeavour for Violet from the start.

Rowland: Honestly, the “staying friends with your ex” thing is such a common shared facet of the Queer Experience that it just felt natural to build that with Kadou and his friend Tadek. I did once seriously consider whether I wanted to structure the book with a love triangle that resolves into polyamory, but in the end I decided that I’d seen that before, but I hadn’t seen very many stories at all that framed a friendship as something as important as a romance, and which could be built with as much deliberate choice and intention as a romance. Too often we see friendship-with-an-ex depicted as a consolation prize, the salvaged scraps from a failed relationship. But friendships are also relationships! We can prioritize them and put in the work to nurture them! They shouldn’t be less important than romantic/sexual relationships, just different.

I’m not sure how I balanced Kadou building a new kind of relationship with his ex while also falling in love with someone new, I just know that it was really, really important to me to try. And perhaps it is simply in the trying that we can navigate a balance between those two things?

Paste: Whether oaths of fealty or magical contracts, these romances never lose sight of the power dynamics involving consent and they reiterate what we do (and don’t) owe to one another. Why was that important to you to include?

Rowland: We all know that power dynamics exist. We all know that even clumsily-handled issues of consent can hurt people. These are real things that real people have to deal with. So by actually facing those issues and talking about them and making the characters as aware of the ethics around them, it means that the reader doesn’t have to do as much work to suspend their disbelief.

A Taste of Gold and Iron is essentially a workplace romance (a boss/employee romance, even). In real life, that’s at best a deeply uncomfortable and complicated situation to find yourself in. My job is to make it compelling and sexy, and that means that textual discussions of consent and ethics—conversations characters have with each other, elements of the worldbuilding, etc—are quite simply non-negotiable. I wouldn’t have been having as much of a compelling, sexy time without those elements.

Marske: I do think that in fiction there’s scope to explore some of those murkier power dynamics that one might find far more concerning than compelling if they took place in the real world, or involved oneself (or one’s best friend!). But it really depends on the kind of story you’re telling and the kind of romance you’re writing. I love that Kadou and Evemer’s romance is about power and what we owe to one another: the profundity of their bond literally could not exist without an exploration of those concepts in-text.

In A Restless Truth, the power dynamic between Violet and Maud starts in one place and ends up—through the process of discovery and exploration—in quite another. And because that is essential to their romance, and because I did let them fuck it up a bit while they’re feeling out the shape of what they might be to one another, they too had to have a frank discussion about consent and power at some point. I am fascinated by characters who agree to stretch the bounds of control and autonomy as a part of sex, and I love exploring the ways in which that can be negotiated.

And that’s before you even get onto the consent process of magical contracts! Which, like so many things in my series, exist as an echo of what’s happening within the relationships.

Paste: What have been the trickiest and the most rewarding aspects of writing fantasy romance?

Marske: Trickiest: balancing the two sides of the coin! There are only so many words allowed in a book (or so my editor tells me; I remain unconvinced). And as I move through my trilogy, I have more plot threads to weave and more of an ensemble of characters to juggle, which leaves less space for the central romance of each book; or at least means I have to make sure most scenes are serving double duty, both dragging the fantasy plot forward and developing the romance. I

‘m still learning how to do that effectively. Drafting involves a great deal of gnashing my teeth and shouting that I’m never writing plot again, never!! My characters are simply going to run away to a cottage somewhere and have a lot of sex and talk about their feelings!!

Most rewarding: when I get the balance right, it means I’m writing exactly the kind of books I most want to read. And then I get to see them out in the world finding the audience who wants to read them too.

Rowland: I definitely agree that balancing fantasy and romance is challenging, but it’s a fun kind of challenge. Though I will caution the audience to remember that whether you successfully hit that balance or not is a deeply subjective thing. (Shout-out to all the Goodreads reviewers who are populating both the “This book has barely any fantasy in it, it’s all romance” camp and the “This book has barely any romance, it’s all fantasy plot” camp, I sincerely appreciate you, and I feel like I must have done a pretty good job because there’s about an equal number of you.)

All in all, I think the challenges and rewards of fantasy romance are the same as they are for any book: First, you simply can’t write a book that is going to work for absolutely everyone. It’s just like opening a restaurant: Not everyone is going to come eat at your restaurant and love it, because they’ve got different dietary restrictions, allergies, and tastes. With books, you are feeding minds and souls instead of bodies—everyone’s brain is different and everyone’s story-hunger craves different kinds of nourishment. So the challenge of writing any book is facing the idea that some people will try it and hate it, and that some people will walk right past and go “Eh, not for me,” and admitting to yourself that that’s okay, that happens, that’s normal.

But the reward is getting to see the powerful joy in someone who has been craving this exact dish for years and who has just eaten the food you made for them until their heart is filled to bursting and who is now asking for a takeout box so they can have the rest for lunch tomorrow.

Paste: I love how Kadou and Evemer are the purest of foils; one can’t be happy while the other is miserable, or one’s comfort depends on the other’s discomfort. What appealed to you in writing this dynamic? What did you have to keep in mind while putting them through various emotional and physical trials?

Rowland: I think the thing that most appealed to me about the dynamic was how it forced both of them to grow as people. At the beginning of the book, they’re both quite static—Kadou is just trying to get through the day and not ruin everything for everyone (thank u, anxiety), and Evemer is just… extremely rigid and set in his ways, and has a strong tendency to view the world in black and white. Both of them need to be picked up and vigorously shaken to get them to move out of those comfort zones.

At first this experience is quite frictionful (is that a word? it is now) for both of them because of how they’re rubbing against each other and stepping on each other’s toes and clashing—and that is certainly one way which people can force each other to grow—but as time goes on and they become closer and start slowly falling in love, it becomes more of a Striving, a thing they’re reaching for and seeking out and working for. They are both coming at it from a perspective of, “He’s amazing, he’s breathtaking. I want to be the best version of myself because of him. I want to be worthy of him, and if I do not strive to be my best self, if I don’t at least try, then I will not be worthy. But the reward I get for trying and working on myself is that we get to take another step closer to each other, which is the thing I want more than anything else in the world.”

When you really love someone, you want to change for them, I think, at least enough to create a space in your life and your heart where they fit perfectly. This kind of relationship isn’t easy, nor without some sacrifices, but when you find someone who is willing to accommodate you just as much as you are accommodating them—and who is joyful about doing so—those sacrifices don’t actually feel that much like sacrifices at all. It starts feeling more like gifts that you’re giving to the other person or good things that you’re happily sharing with them, rather than a price that you’re paying or something that you yourself are losing or giving up.

Paste: I love how Violet regards her and Maud’s dynamic as scene partners. Can you delve more into this for us?

Markse: Was I very into theatre when I was a child and teenager? Absolutely. Was I any good at theatre? Oh, no. My expertise begins and ends at Speaking Shakespeare Well. And improv was the style of theatre least suited to my controlling tendencies. But I continued to do a lot of performing, especially a lot of choral singing and dance, and I wanted to capture that thrill that arises when you realise that another singer is able to improvise a great harmony around your melody line, or you’re doing swing dance with a generous and creative partner.

For a performer-character like Violet, that thrill is one of the kernels of emotion around which a real romance starts to grow: the sense that someone is meeting you exactly where you are and saying yes, and?

Paste: Alex, would you write another fantasy romance in the world of A Taste of Gold and Iron? Possibly featuring Tadek, or Eozena, or Zeliha’s next potential lover?

Rowland: All my fantasy books are set in the same world, in fact! Sharp-eyed readers will spot a reference in A Choir of Lies to the inciting incident of A Taste of Gold and Iron, for example, and there will only be more interlinking references between books as I publish more of them! So in short: Yes, I have a whole world to play with, so I am certain other people in it will eventually fall in love. 😉

Now, if you’re asking whether we might see any future characters from the country where A Taste of Gold and Iron is set: Yep! The book I’m writing right now has one. He’s a trashbag dumpster gremlin that I found in a dumpster behind a Denny’s, and you will love him. Don’t know that we can really call what’s going on with him a romance, per se, but he’s got some interesting relationships to navigate.

Marske: Hilariously, the queer erotica in this series is most integral in the third book, and so I flung it backwards through the other books partially in order to lay that groundwork. As someone for whom reading queer erotica (fanfiction. it was fanfiction.) was very important for that process of questioning and realisation of my own sexuality, I loved putting that in the series.

For Robin and Edwin it’s a quiet moment of recognition—a moment of realising that the other person is safe, a kindred spirit, in an unsafe time period for queer people—which is an initial turning point for their romance. And as I said, for Maud and Violet the erotica creates that space of joyful play which is integral to the way they interact first sexually and then romantically.

And for Lord Hawthorn… well, you’ll see.

A Taste of Gold and Iron and A Restless Truth are both available now from Tordotcom Publishing.

Natalie Zutter is a Brooklyn-based playwright and pop culture critic whose work has appeared on Tor.com, NPR Books, Den of Geek, and elsewhere. Find her on Twitter @nataliezutter.